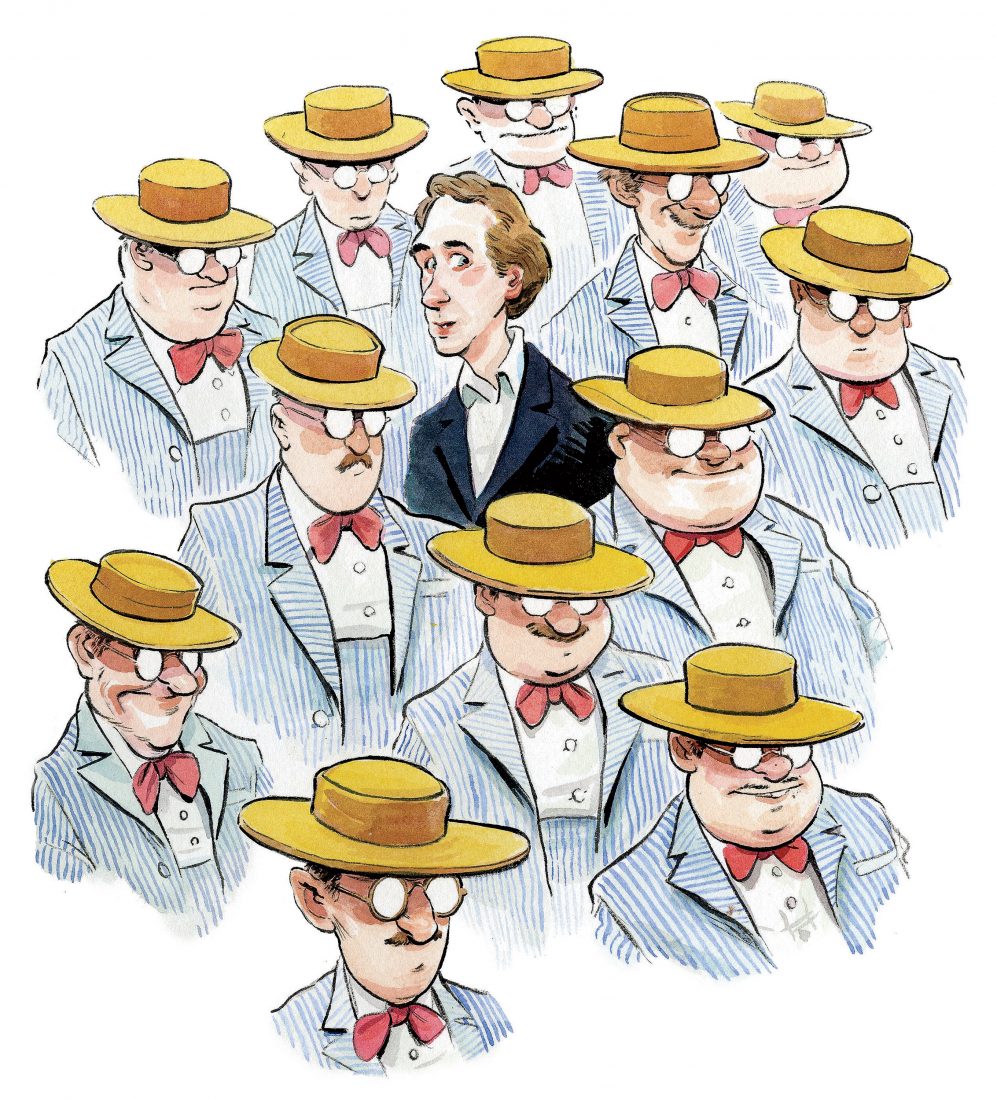

Q. Is there a way to wear seersucker without looking like a lawyer in Mobile?

I can’t say how the Gulf Coast Bar Association created the negative impression, or why, but you’re doing yourself a great midsummer disservice by allowing that presumed style devil to chase you from a fantastically able and good-looking fabric. Admittedly, seersucker is pretty much the uniform of Mobile and New Orleans, but there’s nothing wrong with those boys that a couple of drinks won’t fix, and seersucker abounds on the Gulf for a very good reason. It works hard, and ingeniously, to slough off heat. The secret is in the old British colonial milk- and-sugar weave, in which some of the threads bunch together, creating the wrinkles that keep the fabric off the skin, making it super breathable. It takes its name from the Persian words for milk and sugar, sheer and shakar. But that’s not really your worry. Your worry is how to tweak it. Instead of going with what we’ll call the full Mobile, meaning, wearing the suit with a pair of bucks and a bow tie, take some of the polish off with what we’ll call seersucker satire, teaming the jacket up with a pair of worn jeans, some old canvas tennis shoes—we highly recommend Jack Purcells or a beat-up pair of Chuck Taylors. Or, if you have a minute, run out and buy a 1970s Caddy convertible. Wear some good mean shades. They won’t think you’re a lawyer. What you’ll look like, instead, is that you employ a couple of good ones.

Q. Is it possible for Southerners to ever stop saying “ma’am” and “sir,” or will we be doing that until we die?

You’ll definitely be addressing people with these honorifics until you die—at least, I hope you will, because they carry a quiver of connotations that can be used in any number of sophisticated, complimentary, and cutting combinations. Which is to say, they’re very useful words. They grease the South’s social and professional wheels; they can kill, caress, and do much in between. Full disclosure: I attended a military boarding school, where an instructor of mine once pithily observed that the South was “freely martial.” I think that goes especially for our language. And I was raised by my set of parents, so I still address them with the honorifics. There’s a deep intimacy—the very opposite of a distance—built by the decades in that form of address. Outside the family, the words take a different sort of flight. They spring from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French and English social architecture, the wellspring of the South’s layered, rather soldierly manners. These would be the forms of courtesy that open doors, yet remain sentinel at a wary distance. We can see it in Shakespeare: “How now, good sir?” Not knowing if the meeting will result in an alliance or in a sword fight. Of the two words, ma’am is by far the more powerful, because, as we know, the women of the South actually run everything.

Q. Is hand-churned ice cream the only way to go, or can I cheat and use an electric model?

We could start with the raging taste debate, but let’s go at this through the OT, or occupational therapy, theory of ice cream. As Navy SEAL unit and SWAT-team commanders around the country know, common, task-driven experiences have all sorts of bonding benefits for teams. Placing the task of hand churning a bucket of fresh cream and, let’s say, peaches before your guests will bond them to the common purpose of a) getting to the amazing reward, but b) more to the point, really accomplishing something as a unit, for the unit. By all means plug in the electric paddle if you need a fast batch for whatever reason. But engaging a good, old-fashioned rotation of people at a hand churn is a noble effort for the common good, and will supply your event with an exquisitely finished narrative arc as the results are enjoyed. It also makes for a good bit of comedy when the churning gets harder as the cream ices. It’s a double gain, then, for that bit of pain.