We first saw our Aussie mix on a Texas rescue shelter website. She was mangy, cowering, a little crazy in the eyeballs, ready to bolt, as if she thought the camera might eat her. A doomed hyena. Then a few months later, my girlfriend (now wife), Nell, noticed that a friend had decided to foster that same dog—she recognized her from the old shelter picture. “Rainbow” was a lot healthier now, and obviously beautiful, almost like a wolf, sweet natured. Even though the dog ran off the day Nell went to meet her and came back having rolled in sublimely fresh cow plop, Nell decided to adopt her. “Rainbow” had to go, so Nell renamed her Maji (pronounced “mah-jee”)—she’d heard the word meant “hungry” in some tongue. So from January of that year until the following summer, Nell and Maji lived together in a cabin on a dirt road in Dripping Springs, outside Austin. A huge yard surrounded the house, which was in the country near a lake, and there, Maji pretty much acted like a normal dog. She liked to play. She didn’t bark too much. She did have a tendency to scarf old cat turds she found in the yard, but that’s not unusual for a dog. She chewed sticks to pieces. And she ate well when given real food. Hence, the name.

Then Nell finished graduate school and moved herself and Maji to live with me in Laramie, Wyoming, where I teach young writers how to be more neurotic about their work. We bought a modest 1940s bungalow near campus and began renovating it, ripping out the vintage seventies wall-to-wall carpet to reveal like-new solid oak floors. It was then that Maji’s own neuroses started to manifest themselves.

For one, she was suddenly terrified of the oak floor’s gleaming veneer. Nell’s cabin in Dripping Springs had been an old, small one-bedroom structure with an open front porch, its floorboards painted the same dark redwood color as the wooden floors in the house—a smooth transition from inside to out. Nothing about living in that cabin seemed to give Maji any trouble, not even the constant presence of scorpions that had led to Nell’s landlady giving her a handmade mosquito (read: scorpion) net to hang over her bed at night.

Now Maji agonized over crossing the oak to the safe island of a rug. She hunched down, lowered her nose, spread her legs, and with great force of will inched across to the rug, where she instantly relaxed. The kitchen’s linoleum was no easier, but at least there was less of it.

The appearance (or reappearance, we didn’t know) of her shiny-surface phobia seemed to have either summoned more terror from the depths of her memory, or simply revealed her true psyche, for she was now also afraid of walking through doorways between rooms. She would poke her nose through, but an invisible barrier kept pushing her back. We tried gentle coaxing; we tried a leash. She eventually reasoned that if she went through backward, she would be safe. (She has a very pretty, broad, fluffy butt, so maybe that helps—plus there are no eyes in her rear end.) The two steps from the kitchen down to the garage floor, where she had to go for access to the backyard, gave her trouble, too. And they were right there on the other side of the kitchen doorway, so the problem was twofold—and there was no backing down those steps. After some practice, she became adept enough to get her head through that opening, and then kind of bump her butt against the top stair a couple of times—a little routine—then bump it down to the middle step, and then shoot into the garage toward freedom. I decided to call her particular difficulty “transitional anxiety.”

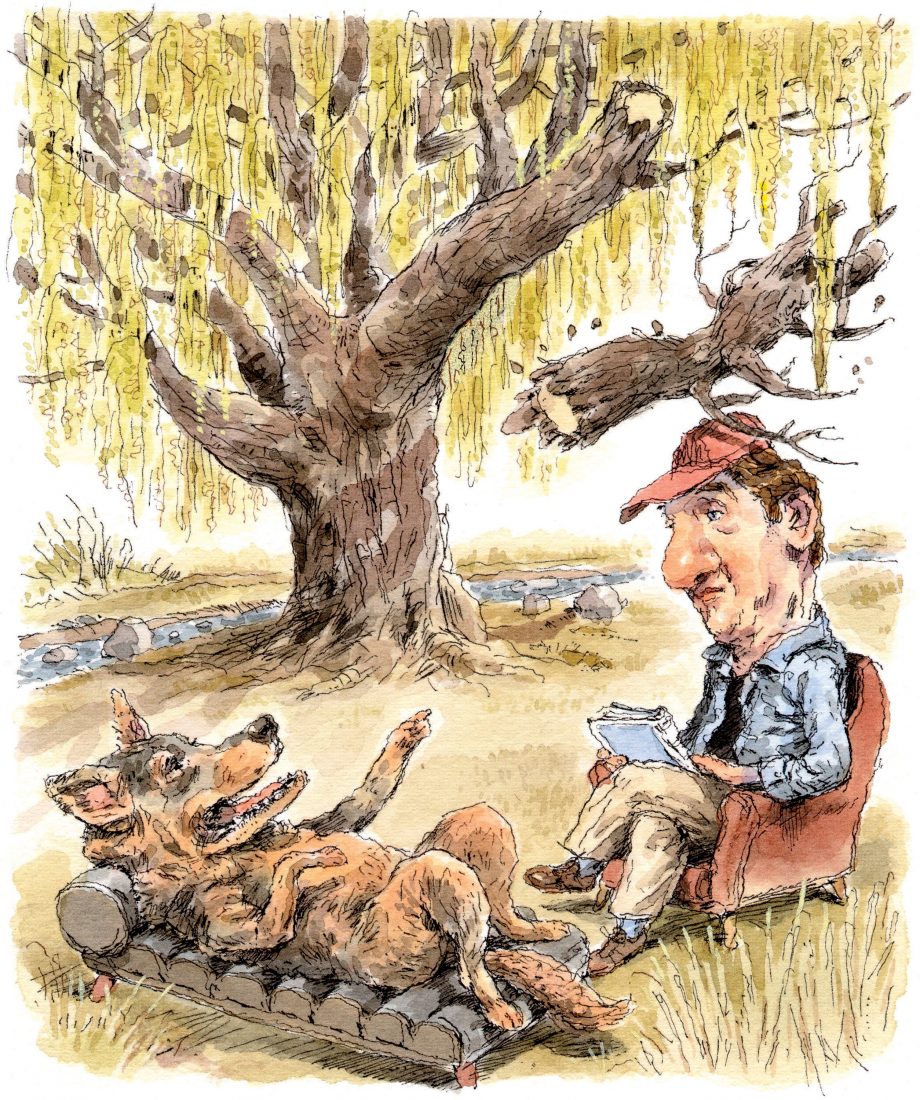

Of course, outdoors, the dog is fearless. She’s gotten hurt countless times by throwing herself into the roughest mountain shrubbery after a squirrel or a rabbit. Stabbed herself in the chest hunting mice hiding behind a bundle of metal tree-seedling protectors. Filled her nostrils to her eyeballs digging in the heavy red dirt to get at a prairie dog. She’s fought larger, much fiercer-looking mutts and held her own. She has no trouble leaping out of my truck, full speed, when we get to our favorite mountain trail just east of town. She’s obsessed with chasing the smallish squirrels up there—once, she was so focused she didn’t even notice a bull elk twenty feet away. She gets a lot of off-leash time out here in Wyoming, and it’s spoiled her good.

Maybe too much, maybe not. But her greater access to the outdoors has made life indoors so lackluster as to depress her appetite as well as her brain. She’s super-sensitive to a critical tone of voice when we wield it inside, but calls to obedience while outside have little effect on her. Indoors, she’s become a finicky eater. Outdoors, she devours rodent viscera and brains with relish. Perhaps she understands that inside the artificial environment of the house, Nell and I have an unfair power over her existence—even if that power is expressed in gushing, spoiling, you-can-have-the-whole-sofa-to-yourself kind of love. Maji seems to possess a human level of intuitive, emotional intelligence. All dogs can detect human mood swings, but she appears especially vigilant on that front, ears up and eyes darting from one person to the other during any conversation that rises above what could lull a baby to sleep.

In ten years, Maji’s neuroses haven’t gone away. She has occasional periods of lessened fear. But in general, she ventures tentatively onto the slick spots (especially when combined with doorways), backing up and starting over several times, as if the floors are really thin ice beneath which lies the long, long fall to the very frozen pits of hell. Her jitters happen in the house, mostly, although they can spring up at the vet, in motels, et cetera. I understand where she’s coming from.

I was a “sensitive” boy. I got teased for that—for how easily I was embarrassed, how simple it was to make me tune up a wail. My father never had to spank me, back when people did that. A harsh word was enough to send me into the depths of guilt-ridden shame. When I knocked a boy down in a boxing match, it was I who began to cry and apologize, even as the boy sat on his ass in the grass with a goofy grin on his face.

And do I have oddball, inscrutable fears? Just ask my wife. She has to live with a grown man who sometimes separates the items on his plate so that no one of them is touching another. This comes from childhood, when for some reason, I ate the food on my plate one item at a time, around the plate, until my exasperated father forced me to stop. I carry Purell in my pocket, every day. I swallow a measure of red wine before eating canned goods, having heard somewhere that it kills harmful bacteria. I walk down sidewalks expecting willow limbs to fall soundlessly from their trunks and crush me. It does happen. A tree surgeon told me so. I may be the most defensive driver in the world.

So when I see this dog, Maji—who is no longer limited by any kind of species-related definitions but is simply a beloved being in our midst—struggling to get across the smooth-surface floor, or through a doorway, or down some tricky, maliciously unpredictable set of stairs, I think I know something about where her head is. How such things can seem to be much greater threats than they might appear to the less aware, the insensitive luckless who will no doubt one day walk off the cliff, fall into the hole, accidentally pass into the next dimension, vanish like life itself must vanish into the invisible vacuum of death.

This dog, much more than most canines, and much more than a silly neurotic human such as me, is smart. A very careful dog, who understands on a deep dog level the treachery of the physical world. Especially when the floors of that world happen to be put together with fragile materials created by the most careless species on the planet: us.

So she tiptoes to her spot, on the daybed or the couch, and lies there, alert, watching and listening. She doesn’t much want to be touched at such times (although a little bit of belly rubbing is usually welcome enough): It’s a distraction. She might miss something important. Something potentially interesting, or dangerous. Only when she’s sleeping does she seem relieved of the belief that something is about to happen, that anything could happen, and when it does she will be ready. And safe.

Then we pick up her leash, and at the tinkle of the dog tags, she’s up as quick as if a rabbit had dashed through the room. An outing is afoot. Real game, real sport, is out there, in the real world.