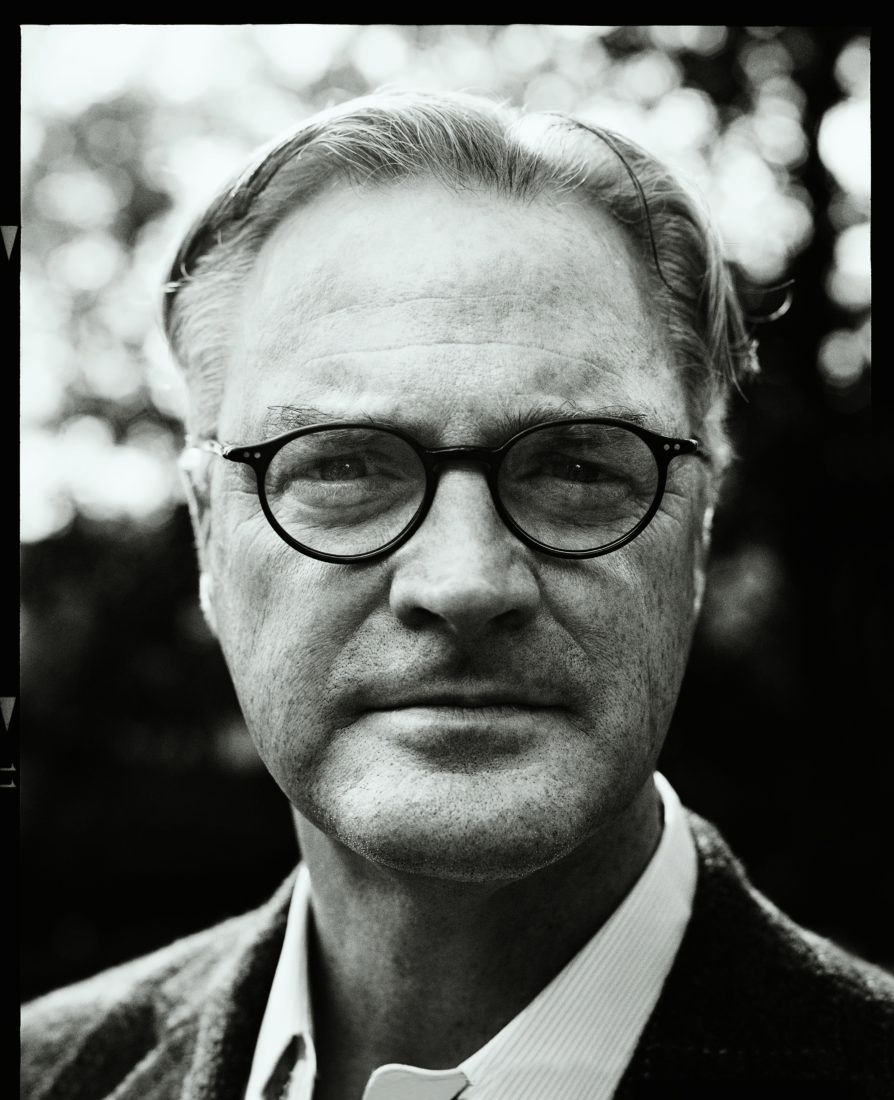

Architect Bobby McAlpine recently debuted yet another accomplishment in his prolific career: the publication of his third book, Poetry of Place. Like his first retrospective published nearly a decade ago, McAlpine narrates this volume in the same thoughtful voice his fans have come to know—that of an architect who speaks more about soulful retreats rather than showplaces. We caught up with him while he’s touring the country for the book, to talk about what drives his designs and what’s next.

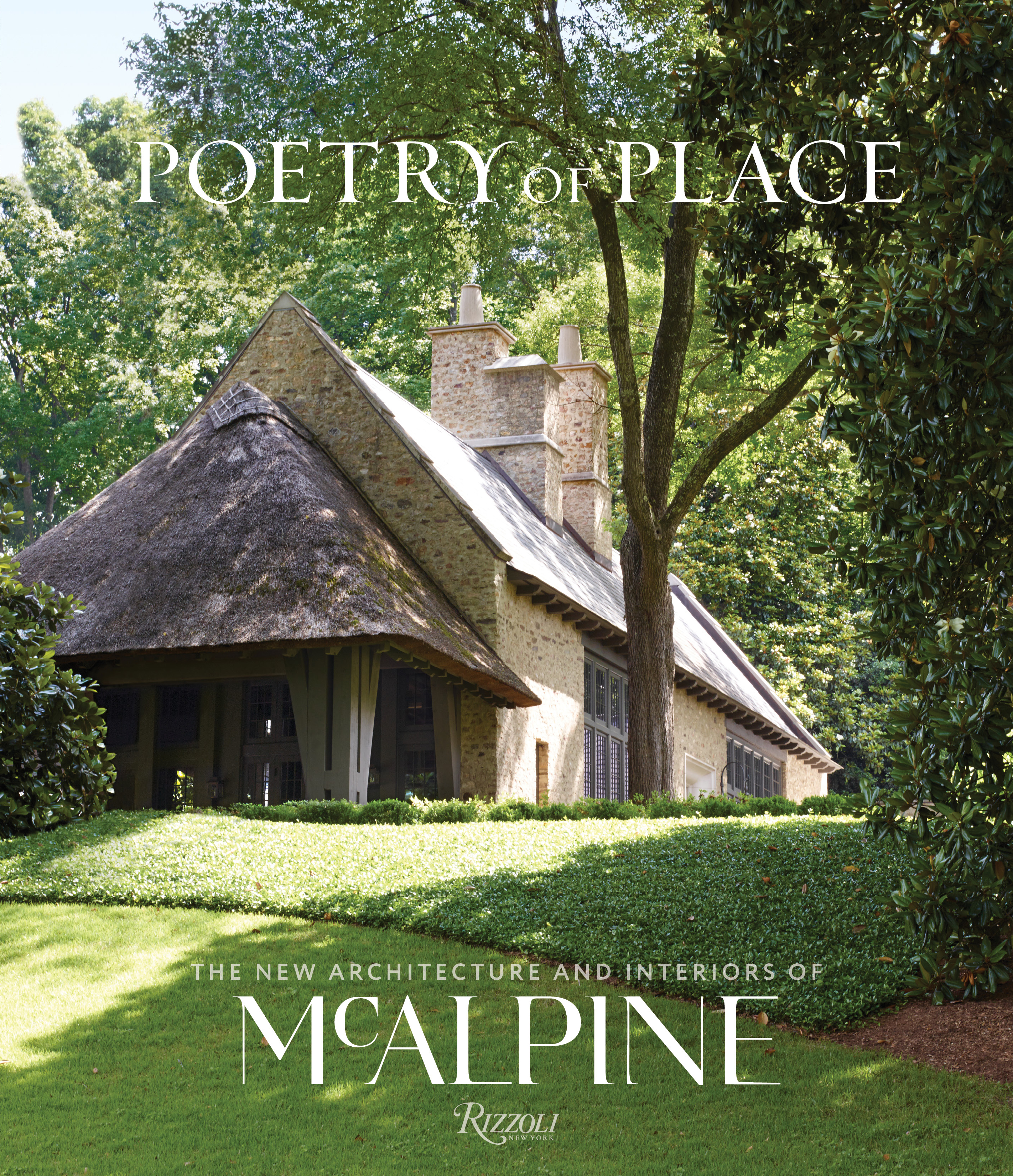

Bobby McAlpine’s third book, Poetry of Place.

What moved you to compile a third book after The Home Within Us?

Our work keeps deepening and it has been seven years since the last book, so it’s good to dial into how our thinking has advanced to now. The houses in this book are portraits; portraits of the people who sat for me and the colors I tuned into when I met them.

One of the things our readers enjoyed about the profile G&G ran about your life and work in 2009 was your ability to articulate the connection that humans have to the concept of home. That rings true in this book as well. Why is this idea so important?

Emotional accuracy is the one thing that the heart knows. It’s more important than whether something is classic or modern. Home matters to Southerners because the heat and isolation groomed us for an invitation to creativity and a going inside; a going into ourselves. When you have the gift to mold your environment, a home becomes a highly particular sanctuary.

Photo: ROGER FOLEY

Long Leaf Fishing Camp in Butler County, Alabama, April, 2015.

There is one house in the book that jumps off the page as a place you would only find in the South. It’s a beautiful cottage on a lake in the middle of the Alabama wilderness. Tell me about how you came to design this property and why land dictated so much of the design.

The owner told us he wanted to fish from his porch, so there is nothing between the house and the water. The color was chosen to stand out against the landscape. It needed to be unkempt and raggedy. It looks like the truth, which is always elegant.

PIETER ESTERSOHN

You intrinsically understand the importance of light, of fusing the barrier between the occupant of a house and nature. What is your philosophy on that subject?

Windows become witness to that love of being inside as well as outside. I like being held in a house and I do a lot of divided light windows. I like the veil. I like being protected but also able to see.

PIETER ESTERSOHN

You are a proponent of choosing materials with integrity. What are some of your favorites to work with and why?

The test of any material is whether it has the capacity to become more beautiful over time. My all-time favorite is thatch. I love mixing the perishable with the imperishable and using it with steel and glass. And in general, I gravitate toward materials that are not trackable to a particular time period.

EMILY FOLLOWILL

The word retreat is the title of an entire chapter, the subject of which is a lake house. How do you design homes that are built specifically for rest differently than primary residences?

Retreats give you the ability to hand over the reins to nature. Everything else takes a backseat to what the healing context is. The materials dim themselves into the environment and don’t make a noise unattractive to the place itself. A common tool I use is compression. Most new residences make you feel like a Tic Tac rolling around. To sit in a window seat or a nook: those are the places where you feel the benevolence of the house. From that position, you can accept a larger invitation into the world.

What’s next for you?

I’m already onto another frontier. We’re known as being romantics not modernists, but my new personal home in Atlanta is different. It says in five words what I would have said in eleven before.

Poetry of Place is available now.