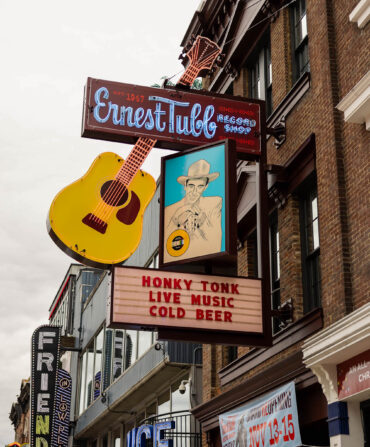

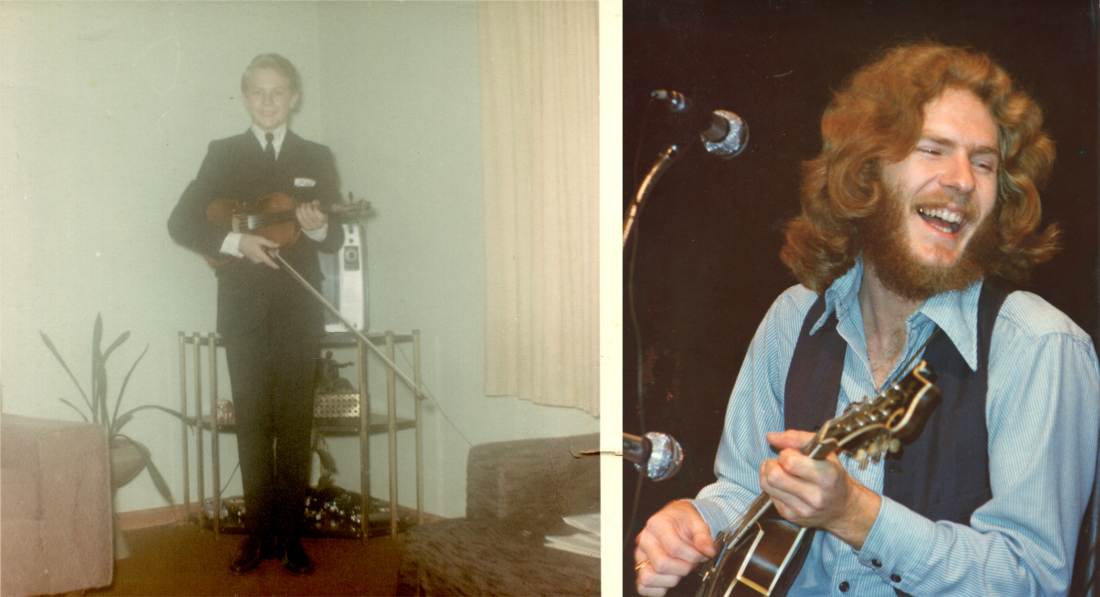

When Sam Bush started winning fiddle contests as a teenager in the 1960s, bluegrass musicians fit a certain framework—clean-cut men with spiffy suits who drew from a songbook that dated back centuries. Bush broke that mold. Sure, he could play the fiddle and the mandolin as well as any traditionalist, and his upbringing in Bowling Green, Kentucky, supplied plenty of education in bluegrass music. But he wore his hair long, dressed in casual clothes, and began forging his own path with his band, New Grass Revival.

Photo: Courtesy of Sam Bush

From left: Bush with his first fiddle; Bush in Seattle Washington in 1976, performing with Byron Berline and Mark O’Connor.

“There’s something to be said for being young and hard-headed,” Bush says. Revival: The Sam Bush Story (streaming now on Amazon) shows just how far that mindset took him. The film follows Bush’s evolution from standout instrumentalist to band-leader to revered pioneer. To tell the story of Sam Bush is to tell the story of an entire generation of musicians—his willingness to color outside the lines laid the groundwork for artists like Chris Thile and the Avett Brothers. Today, even when he’s not the best-known name on a festival bill, Bush’s influence is among the farthest-reaching.

“He was heroic to all of us because of what he stood for,” says Alison Krauss, who appears in the documentary alongside musicians like Emmylou Harris, Del McCoury, and Ricky Skaggs. “There’s nobody else that all the traditionalists adore, yet is also on the absolute cutting-edge of this genre. Everybody looked up to him—he’s like the Robert Plant of acoustic music.”

Krauss, an icon in her own right, has plenty in common with Bush—both began performing at an early age, passing on opportunities to join established bluegrass ensembles, and forging paths with their own progressive bands. So in the wake of Revival’s release, G&G caught up with Bush and Krauss to talk about the evolution of bluegrass, the community that nurtured each of them, and the artists they believe will continue to carry the torch.

How did you first become aware of each other?

Krauss: I first heard Sam on records. I listened to New Grass Revival like I was going to school. If you saw Sam Bush on a record, you bought it—just because of what he stood for. There’s no one who can imitate him. His singing and his playing were like nobody else, and he had that thing that made you want to better yourself as a musician. I met him at the Kentucky Fried Bluegrass Festival, back in 1986. That was the first time I saw New Grass Revival. There are pictures that my parents took of me watching them with my mouth hanging open. [Laughs] Oh, I see it now and I’m like, good grief, why didn’t somebody tell me to shut my jaw?

Bush: [Laughs] I was the producer for the winner of the contest at that bluegrass festival—one band would get to go to Nashville and make a record with two songs. When Alison Krauss and Union Station came on to compete, I knew this group was different. Sometimes when you meet musicians—for example when I met Alison, or Mark O’Connor, or Chris Thile—you know immediately that you’re seeing a youngster who is already on the path to having their own sound and their own thing to say. Alison, right off the bat, was making her own way.

Photo: Courtesy of Sam Bush

New Grass Revival (Bela Fleck, Sam Bush, John Cowan, and Pat Flynn) at the KFC Bluegrass Festival in Louisville, Kentucky in the 1980s.

Did either of you ever feel pushback when you started to stray from tradition?

Bush: Oh, just our whole first album, yes. [Laughs] We definitely got a not-so-good review—and the person who reviewed the album was a friend of ours! Right off the bat, it lets you know: not everybody’s gonna love what you do. But we said, So, do we?’ ‘Yep!’ ‘Then, we’re fine.’

Krauss: The same thing happened with a record of mine—it just got destroyed. People who love traditional music, they daydream about the past. In traditional bluegrass, the subjects are home, God, family, the land—it’s all very romantic. When you mess with that picture, people don’t like it. And you know what? I get it. I understand it, and I respect it—that desire to keep something so pure.

Bush: There’s a section of my brain that’s probably a traditionalist. The only people I want to hear do “Rocky Top” are the Osborne Brothers. The only person I want to hear do “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” is Earl Scruggs. And the only person I wanna hear “Rawhide” by is Bill Monroe. [Laughs] I’m still such a fan of the traditional ones that made me want to play.

Krauss: I think about the same thing. You don’t want anybody messing with what made you who you are.

You both attended bluegrass festivals growing up. What about those experiences shaped you as artists?

Krauss: Growing up in that environment, you could go and talk to your favorite musicians while they were sitting at the record table—nine times out of ten, there wasn’t even a backstage! The people onstage played offstage, too, alongside the people who were camping to watch the festival. It was a really loving environment. Didn’t you feel that way, Sam?

Bush: Absolutely. I’ve often wondered if the way we all grew up playing—not reading music, but sitting in a circle and jamming—didn’t give us an edge. We all sat together, and still do.

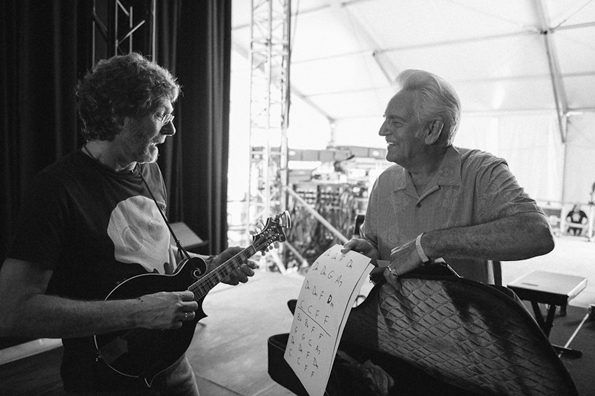

For example, when our band the Bluegrass Alliance played at Bill Monroe’s festival, Bean Blossom, in 1981, it just blew my mind that John Hartford and his band were there, too. But then when they got off stage, Hartford turned around and said, Well, y’all wanna go jam? And we played all night. The bluegrass community is very generous and giving to each other in that way.

Krauss: That festival was actually my first bluegrass festival—Bean Blossom in ‘83. It was the first place I saw Del McCoury, the Osborne Brothers, Jim & Jesse, Ralph Stanley…

Bush: And you also got to marvel at how Bill Monroe could walk around a soggy festival in white patent leather boots and get no mud on him. [Laughs]

Photo: Courtesy of Sam Bush

Bush maps out a set list with Del McCoury at Bonnaroo in 2014.

What makes you the most excited for the genre’s future?

Bush: I see a lot of promise in the ladies of bluegrass. It should never have been a ‘good ol’ boys’ club, and now it isn’t anymore. At the World of Bluegrass, Sierra Hull is winning the mandolin awards, Becky Buller’s won fiddle and singing. Kristen Benson’s a great banjo picker, and you’ve got Missy Rains on bass. Of course, Molly Tuttle is now leading the pack on guitar. And who do you think’s been one of their main influences? Alison has. Those are some pretty heavy-hitting musicians right there, and personally, I just love seein’ ’em kick the good ol’ boys’ asses.