To my friends I’m Jay; to my kids, Dad. To the government and Delta Air Lines I’m Howard James Busbee, Junior. But to my parents, I’ve always been Jay Birdie. As nicknames go it’s not a terrible one.

I’m a sportswriter, and after each game, race, or tournament my father and I carried on a decades-long tradition. I’d call him on the way out of the media parking lot and we’d dissect what we’d both just seen, exulting in the glories and laughing at the misfires. And every time I phoned, he’d answer, “Hey, Jay Birdie!”

My father died two years ago in May. And as anyone who’s lost a parent knows, it sneaks up on you in ways you don’t expect. It would blindside me when I was on the road leaving Truist Park or Sanford Stadium: Hey, I should be calling Dad right now.

One afternoon about a year after he passed, I was in Pinehurst, North Carolina, covering the U.S. Open. Now this will not endear me to those who think the media is a horde of coddled crybabies, but…they feed us really well at these tournaments. I’ve been known to walk an extra nine holes to work off the beef ribs or banh mi or locally sourced hot dogs they serve in the media tent each day.

On this particular afternoon, as the heat rippled up off the Sandhills, I stopped to grab a bite to eat and was pleased to see the day’s offering was Carolina barbecue—minced pork, neon-yellow vinegary coleslaw, and salty warm corn sticks. Something about the sight of it tickled the back of my mind, but I chalked that up to the usual fifty thoughts swirling in my head while on assignment.

And then I took a bite, and bam. The meat, the corn sticks, the slaw—they all seemed incredibly familiar, like a snippet of a song you haven’t heard in decades. A madeleine soaked in vinegar.

I looked at the royal blue script on the white shirts of the gentlemen dishing up the glorious spread—PARKER’S BARBECUE, WILSON, N.C.—and it clicked. This was Dad’s favorite barbecue in all the world, right here in front of me once again. There are coincidences…and then there are moments when the universe aligns itself perfectly for you.

I felt an almost physical need to call my father and tell him what I’d found. Instead, I had to compose myself before going back out and following Rory McIlroy around.

And as I did, I made a vow to myself: Get back to Parker’s. For Dad.

At one time, Wilson, North Carolina, was the world’s largest producer of bright-leaf tobacco, according to the Wilson County Tourism Development Authority. Wilson rewarded entrepreneurs who could meld innovative farming techniques, fact-based financial management, and government-agency sweet-talking—entrepreneurs like my great-grandfather, Howard Watson.

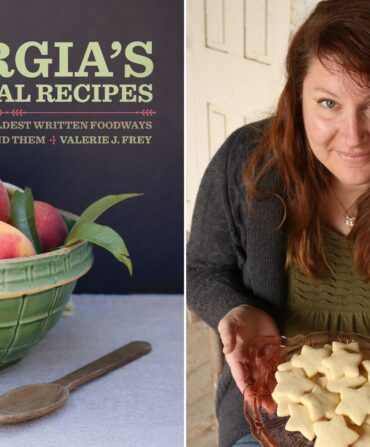

My father idolized his grandfather and namesake, and family dubbed them “Big Howard” and “Little Howard.” (In an eastern Carolina accent, “Howard” becomes “Ha’rd,” and so my siblings and I loved to call my dad “Little Ha’rd”…once we were old enough that he couldn’t ground us.)

Big Howard owned and operated 516 acres of tobacco and other crops. He was such a levelheaded member of Wilson County’s business community that a 1958 farmers’ newsletter praised his “commonsense approach without any folderol,” a word that really ought to come back into style. When my father and his brother Irvin would visit, Big Howard would take them around to his farms…and then he’d take them to Parker’s.

“Parker’s was the Holy Grail,” Uncle Irv told me recently. “You always got your money’s worth, and you’d always go home with a pint. It was a great treat to go to Parker’s.”

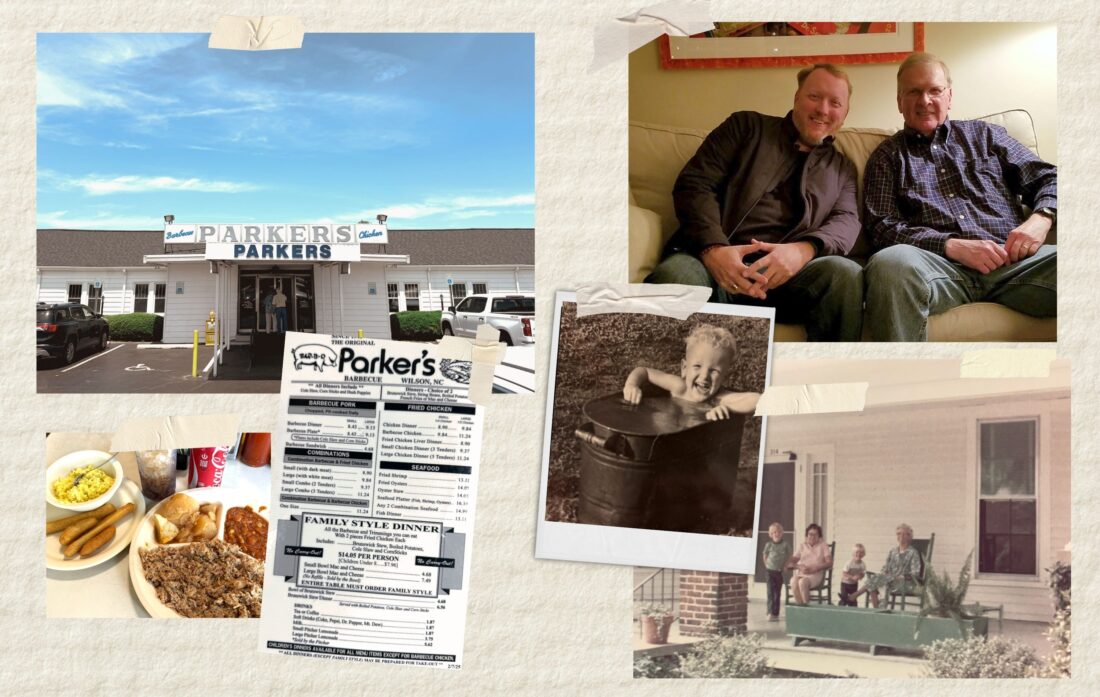

An eastern North Carolina institution, Parker’s has stood on the same spot just outside Wilson, along Highway 301, for nearly seventy years, dishing up ’cue from generation Silent to Alpha.

“There’s a joke around here,” says Brandt Harrell, who grew up in Wilson and now serves as the executive director of the tourism authority. “When somebody’s born, married, or dies…you eat Parker’s.”

I rolled into Parker’s the morning after the PGA Championship in Charlotte last month. It looks pretty much the same as I remember it from coming here as a child myself, pretty much the same as it did when my dad came here as a child himself—a wide, single-story building, its bright white siding set off by that distinctive blue PARKER’S sign on the entry foyer. Inside, old photos of the restaurant cover the wood-paneled walls, and in them, only the cars out front have changed.

The menu is wonderfully precise—$4.68 for a barbecue pork sandwich, $11.24 for a combo plate (barbecue and three tenders of fried chicken), $14.05 for a family-style dinner (all the barbecue and trimmings you can eat, limit two pieces of fried chicken, ENTIRE TABLE MUST ORDER FAMILY STYLE).

“It’s the type of food that brings people together in this part of North Carolina,” Brandt says.

“You’ll have community events like pig pickings. The fire station has a fundraiser where they cook Brunswick stew. Parker’s does all that.”

I can see why this place delighted my father, a man who never turned down a chance to sample smoked meats. Whether at ZZQ in Richmond or Heirloom Market in Atlanta or Three Little Pigs in Pine Mountain, Georgia, Howard Busbee was a barbecue obsessive. We’d text one another pictures of our plates, we’d tip each other off to new discoveries (“You gotta stop at Lexington!”), we’d share table after table all over the South.

My father wasn’t a deeply religious man, but he was a spiritual one, and pulled pork and Brunswick stew were his communion. You’ve never seen a happier fellow than my father when surrounded by children and grandchildren, a plate of fall-off-the-bone ribs on the table before him. We never got up from one meal before planning where we’d gather for the next one.

My father and I talked on the phone several times a week, sometimes getting deep, sometimes just bitching about the Falcons or the ’Noles. He had a way of setting the stage for me, giving me all the room I needed to spin tales or talk about my kids or just rant.

But over the last two years, a growing, grim realization has set in. I know so little about my father’s history. I know he loved Parker’s, sure, but it took a call to my uncle and some deep dives into family records to even get a sense of what Little Ha’rd’s young life was like. And that forced me to confront some uncomfortable, maddening questions.

Why did I take me so long to track down his stories, and how many more have already faded away, lost forever? Why didn’t I talk less on our phone calls, and listen more? Why didn’t I ask more questions when I had the chance?

At Parker’s, I finished off my plate—the pork, slaw, and Brunswick were perfect, as expected—and ordered a sack of corn sticks to go.

“That’s how you know you’re dealing with a local,” Brandt laughs. “They know to ask for corn sticks instead of corn bread.” I’m no local, but I learned from one. That lesson, at least, had stuck.

The lunch rush was on now, and my server, dressed in a natty white uniform and a paper hat, same as untold generations before him, didn’t have a whole lot of time to stand around and talk ancient Parker’s history. I paid my tab—cash only—and walked back out through the same front door my father had walked in so many times and years before.

Then I looked out over Highway 301, feeling like I’d stepped out of time. My father, and his father and grandfather, had stood right here before, hearing the sound of traffic, smelling the sweet scent of smokers, feeling the warmth of the Carolina sun.

In that moment I felt as near to my father as I have since his passing. So I did the closest thing I could to calling him. I pulled up one of his old voicemails.

“Hey, Jay Birdie, it’s Dad checking in.” As if I wouldn’t know who it was. As if I won’t know that voice every day until I join him. He ran through a list of whatever was on his mind that day back in early 2023—Mom out running errands, one of my brothers coming to town, his plans for the weekend. The specifics didn’t matter, just the sound of his voice, and behind my sunglasses the tears flowed.

He wrapped up this ordinary, precious call with his usual sign-off—“Love you! Bye!”—and I said out loud, “Love you too, Dad,” like he could hear me. And heck, in this place, maybe he can. He’d want me to get him a pint of pork to go, I know that much.

I also know this: Many of my father’s happiest childhood memories—memories of the warm embrace of family, memories of his own towering grandfather—came over a plate of barbecue at Parker’s. And he spent the rest of his life re-creating that sense of belonging, that love that crossed generations, for his own children and grandchildren. It’s a gift of immeasurable value, delivered with a side of coleslaw.

I got back in my car, pointed south toward Atlanta, and called my kids. Told them about Parker’s, and about their great-great-grandparents’ Wilson house, and about how their granddad used to live for visits to this lovely town. My tears were still there, but so too was a deep sense of satisfaction and gratitude, the right closing chord played at last.

And as I drove, I worked my way through that warm to-go bag of Parker’s corn sticks. They’ll tide me over until I can bring the kids back myself. And oh, will I have questions to ask of them, and stories to tell.