Some artists flock to New York City to find fame within the art scene, but the Mississippi native Dusti Bongé never lost sight of her beloved hometown, Biloxi. In fact, illustrious American painters, including Mark Rothko and Theodoros Stamos, came to visit her in the South, where she painted and drew for more than sixty years until her death in 1993.

After she spent her twenties in New York with her husband, the artist Archie Bongé, she returned to Biloxi in 1934 to raise her son, Lyle. But she didn’t head back home without leaving an indelible mark on the big city’s creative stage. While in New York, Bongé forged a lifelong friendship with the famed gallerist and artist Betty Parsons, who represented the imaginative Abstract Expressionists Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman.

Considered to be Mississippi’s first Modernist artist, Bongé started painting alongside her husband, who encouraged her to nurture her expressive, natural talent herself rather than attend art school and receive formal training. After he passed away in 1936, Bongé—then a widow and a single mother—turned to art for therapeutic healing, taking her sketchbook out to Biloxi’s Back Bay and harbors. She gravitated toward the town’s natural coastal beauty, drawing up geometric renditions on-site of fishing camps, shrimping boats, and shoo-fly decks.

When the circus arrived in Biloxi, she explored abstract forms of performers, cage structures, and animals. For Ligia Römer, the executive director of the Dusti Bongé Art Foundation, the circus series paintings speak directly to Bongé’s innovative vision. “Bongé would visit before the show was up, sketching and painting the big tents,” Römer says. “Her circus series was about her direct experience rather than trying to depict it accurately. It’s very magical. She could see the surreal in everyday life.”

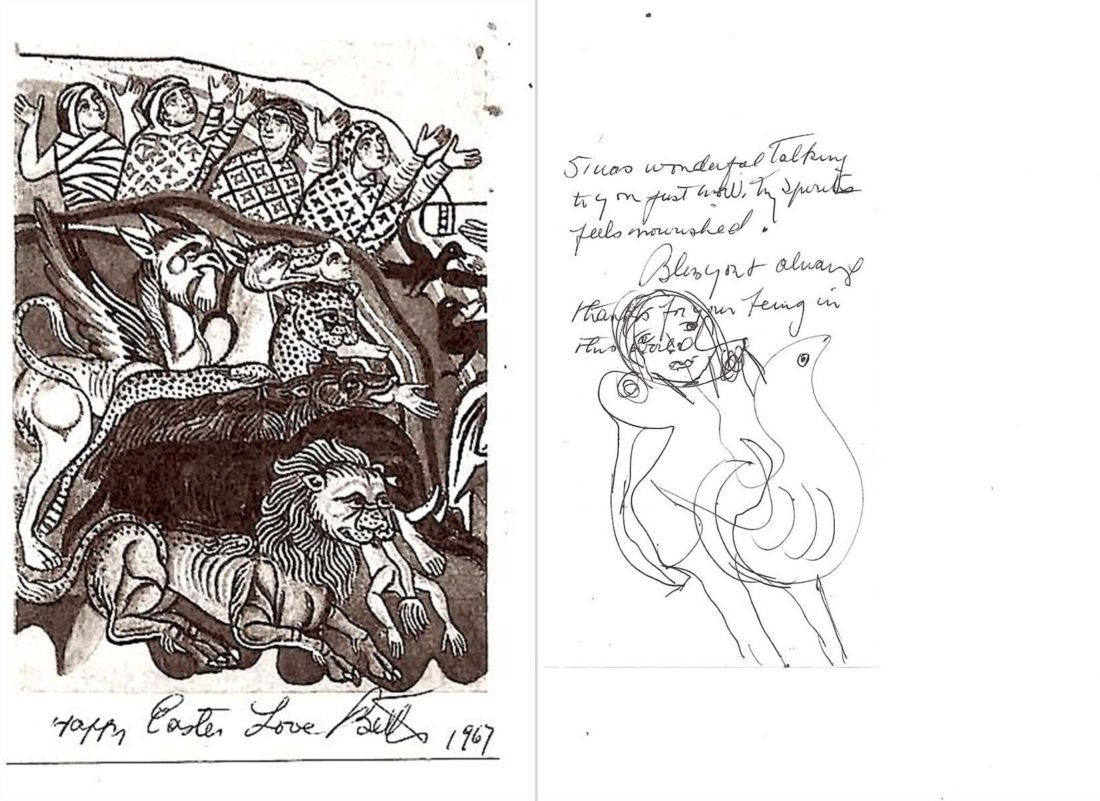

By the fifties, Bongé had joined Parsons’s male-dominated stable of avant-garde artists, exhibiting her work at Parsons’s gallery in New York. Despite the cross-country distance, the two women kept in touch, exchanging intimate notes and drawings on paper, organizing solo and group shows in New York, and joining together to travel to Mexico and the Bahamas.

This fall, the show Kinship: Dusti Bongé and Betty Parsons at New York’s Hollis Taggart Gallery will celebrate the two creatives from October 13 to November 12, debuting their never-before-seen notes and artwork. With thirty-five works from Bongé (and fifteen from Parsons), the exhibition offers an overdue spotlight for the lesser-known Mississippi artist. From her grandson’s expansive collection at the Dusti Bongé Art Foundation, Taggart organized a group of artworks to depict the stylistic evolution across Bongé’s lifelong career.

The gallery’s most pressing challenges included cleaning some never-before-seen pieces and packing artwork for a 1,200-mile journey to New York. But, for Taggart, the project was personal: “I grew up visiting my grandparents in Biloxi,” he says. “And when it comes to art in the South, it never receives the time of day. I wanted to offer recognition for an artist who was lost and forgotten in the shuffle and put her where she belongs in the pantheon of Abstract Expressionist artists from her period.”

Within the South, Bongé’s work can be found in the permanent collections of New Orleans’s Ogden Museum of Southern Art and the Mississippi Museum of Art. The Dusti Bongé Art Foundation in Biloxi, where admission is free for all visitors, always has her work on display. And, in New York, Taggart hopes to bring more of the South’s artists within the national spotlight. “There are many reasons why Southern artists were lost and forgotten,” he says. “But that doesn’t mean that they should have been.”