In the late 1970s, a plucky teenager named Dolly Freed wrote a book called Possum Living. The book’s unforgettable subtitle: How to Live Well Without a Job and With (Almost) No Money. Freed and her writing became instant hits when the book was published in 1978. Readers were fascinated by this no-nonsense teenager who lived on—and off of—half an acre of land near Philadelphia, raising and eating rabbits, distilling liquor, and swearing off most material possessions.

The 1978 original.

Memorable sections include this advice for turtle hunting: “Some people reportedly play turtle roulette. They feel around in holes in banks … I don’t know anything about this technique. If you want to learn it, go to any rural town and ask for Lefty.” The original Possum Living also included a controversial chapter on how to take legal and financial matters into your own hands to maintain your freedom (perhaps from tax collectors or assessors), including vigilante justice tips. Most of the book, however, was a charming, rambling look at how one eighteen-year-old had already decided to drop out of the rat race to live as a “possum,” sometimes taking odd jobs, saving money, growing tomatoes and drinking moonshine. As Freed describes it in the book, “to drift along from day to day… We live this way for a very simple reason: It’s easier to learn to do without some of the things that money can buy than to earn the money to buy them.”

Photo: Courtesy of Dolly Freed

Dolly Freed as a young woman.

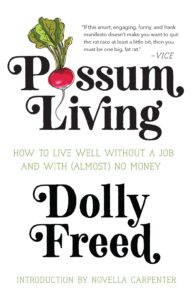

The newly updated release.

Forty years later, Tin House books re-released the title this month. In the new version, Freed provides an afterword. “I wrote Possum Living when I was a cocky eighteen-year-old. The amazing thing is how it’s still right on target,” she writes. “Prices and technology have changed, but the principals are the same.”

We caught up with Freed, who after the book’s first publication, went to school to become a NASA engineer. She moved to Texas, raised two children with her husband, and now tends a big garden and lives, as she calls, it, as a “half-possum.”

Possum Living struck a chord with people. What was the attention like in the seventies and eighties?

I had to get a phone so I could do interviews. When I went to New York to do a TV interview on the Bill Boggs show, they told me to wear something nice, something I wore daily. I put on my nice yellow gardening dress and my yellow gardening hat. I didn’t have a suitcase so I took a burlap bag. They asked about my food, so I packed a sample “possum” feast of flatbread and rabbit. When I came out of Grand Central Station, I watched how people got a taxi. I stuck my arm out, a taxi stopped, and I jumped in the front seat with my big burlap sack and my yellow gardening hat, and the driver said, You have never done this before.

On the show, Bill Boggs started giving me a hard time about buying my clothes at thrift shops, but then we had a great interview. After a while, the publicity was grueling and I just went back to possum living. Years later, we were trying to find some of the clips, and Bill said he remembered me because I was the only person who ever brought moonshine.

You were just a kid when you wrote the book. What was your writing and publishing process like?

I had dropped out of school in the seventh grade, so my mom gave me her typewriter so I would go get my GED. I went through my mom’s typing book and taught myself to type. Well, the typewriter was broken and it wouldn’t return, so I had to tie a huge rubber band to it and staple the other end to the wall so when I clicked the return button it would fly back.

We had a lot of free time to talk, to sit around the table, and write. I typed it all up. I went down to the library and got a book that listed publishers. I sent sample writing and cover letters to ten or twelve publishers. Some said no thank you, some didn’t answer, and one said this looks interesting and you should consider getting an agent. I went back to the library and had the librarian request a book of agents. I found one who did how-tos, and she picked it up and sold my manuscript to Universe Books.

Courtesy of Dolly Freed

You live in Texas now. How did you get there?

I decided I was ready to take on a bigger challenge and go back to school. I worked a year to save up money and started college when I was twenty. It was the equivalent of community college. I did my last year at Drexel University because they had a co-op program to learn about engineering. Then I went to Langley [NASA Research Center]. I met my husband there. I decided I wanted to be a NASA engineer, and I accepted a job at Johnson Space Center here in Houston.

I eventually realized that being inside was not for me. Always being on a computer was not for me. I had been volunteering at Armand Bayou Nature Preserve and it was a lifesaver. I could go canoeing for miles and not see anything manmade. I started helping with the trails and outdoor classes, and I finally realized I needed to make that my career.

It was hard to give up all I had put into being an engineer, but it was so obviously the right change for me. I consulted for environmental education programs around Houston and some of my outdoor programs are still running, twenty-five years later. Southern nature saved me, in a way.

Do you still live like a possum?

It’s not like you are or you aren’t a possum. It’s a sliding scale. You can be full possum and not have a car or a phone and really keep life to the basics. Or you can do half-possum, which is what I’m doing now. I have pets and I’m not going to eat them. [Laughs]. I have a car. I have a big garden. I cook all the time. Just knowing that I have the skills to live and be frugal has made so many potential life emergencies easier—my decision to change careers, my husband’s decision to retire early, my mom getting sick and moving in with us. We know that if everything goes to hell, we can live.

Looking back, what are some of your reflections on the first edition of Possum Living?

When you’re eighteen, it’s easy to think that what you’re doing is the right thing for everybody. But of course it’s not. Not everyone is going to want to be raising rabbits to eat and living without a car. But now that I’m older, I think there’s a lot that’s good about part-possuming. I’m going to be sixty next year. It’s interesting to me to look back all this time later, and think a lot of this is really valid today.

I’m going to get philosophical here, but I think about this a lot. When people talk about poverty, there are different kinds. There is a poverty of status in our country where you have all the food and water you need but you think other people are doing better all around you. You can also have a poverty of control. You feel you can’t choose how you spend your day, when to get up. We don’t talk about those kinds of poverty a lot. Possum living is about taking control of what you want in life.

Is there anything you need to set the record straight on?

There were some pieces about law enforcement that I wanted taken out of the updated edition, but the publisher thought it was a valid insight into some kinds of rural thinking and independence. I don’t go around terrorizing people any more. And in retrospect, that’s not a good way to go through life. Knowing how not to be intimidated is important, though. Sometimes I see someone out drinking beer in the nature center, and I have no problem saying, You’re going to pick those up and leave here now. I’ve come to see over time that it’s much more effective to work with the community than try to threaten someone to do something.

I also don’t make moonshine anymore.

Do you still go turtle hunting?

I’m going to stay neutral on the turtle issue. Turtles are good eating, but the problem with some animals is that they have been overhunted or overfished, and often not for local consumption. Usually when people are hunting for themselves, they tend to take good care of the resource and the environment. I think you can feel good about eating invasive species and not harming the environment. Down here, there are competitions for catching and cooking carp and lion fish. Look how much land is preserved by duck hunters and fishermen. They want to keep enjoying it.

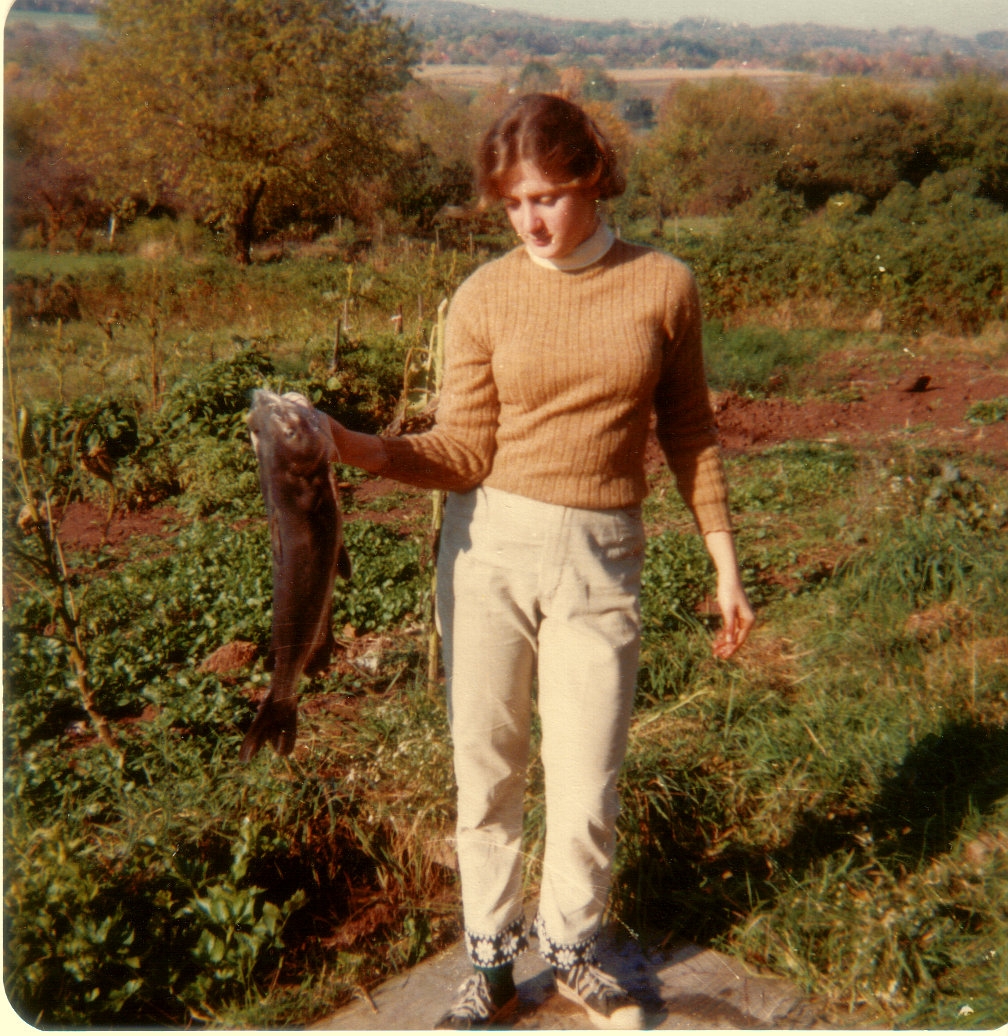

Photo: Courtesy of Dolly Freed

Freed shows off a fresh catch.

Is your garden still a big part of your life?

I still get excited every time a tomato seed sprouts. Even if it was just a basil pot on the balcony when I was in college, I have always been growing plants. Knowing you can garden matters. Having a little spot to tend gives you confidence when the economy and politics are out of your control. You’re taking a seed and some dirt and making something from nothing. That’s empowering.

In the afterword, you write about how you’re helping a younger generation learn to grow their food.

If you don’t know how to garden and you want to start gardening, ask someone. Help them if they’re older. Help them if they’re younger and new to it. Now I get to be the wise old garden lady. My biggest pieces of advice are: Start small and get a water meter from the hardware store. It will show you how to water things properly. And I always remind people, what’s the worst thing that’s going to happen if something dies? If it’s not perfectly weeded, it’s ok, we’re not depending on gardens for our lives anymore. This is just for flavor and fun.

The most satisfying thing about gardening is the food tastes great. Right now, I’ve got lettuce and greens and snap peas coming up. I’m not rich. I’m never going to have the best wine. But I have eaten the best peas that anyone has ever eaten in the history of the world.

Photo: Courtesy of Dolly Freed

A teenaged Freed tends to her garden.

Our readers are going to enjoy hearing this update from you.

Tell them, and this is just an aside, but I really like being a Southerner. I have no desire to ever go through a Pennsylvania winter again. Yeah, we have hot summers down here, but I don’t have to shovel the heat.

I also love the waterways here. I love how people will be fishing off a little scrap of land against the lake or bayou, and a little dinky spot is home to herons and pelicans. People understand when fish are coming or going. When I first moved here, I missed hills, but I’ve come to realize that in Texas, we have the sky. I can see the storms coming in and the low clouds and the sun dogs. I think I am a full-blown Southerner now.