In the Alabama parking lot that changed his life forever, the author Sonny Brewer turned toward me in his driver’s seat, called his dog, Bobby, into his lap, and told me the serendipitous tale of how his first novel came to be. We were sitting in Fairhope, the little city perched on Mobile Bay along the Gulf of Mexico where people come to eat, drink, and unwind. It’s also a place where pretty much everyone has a story to tell.

Forty years ago, Sonny was “a carpenter with a creative writing degree,” building a carport for William E. Butterworth III, a best-selling author of military novels under the pen name W. E. B. Griffin. One day, Sonny’s saw blade buzzed through a board and grazed his pants. He didn’t bleed, but it was what academics might call “an inciting incident.” Sonny scrambled down the scaffolding, banged on his client’s door, and declared he was through with carpentry. He would be a writer. Butterworth promised to help—once the carport was done.

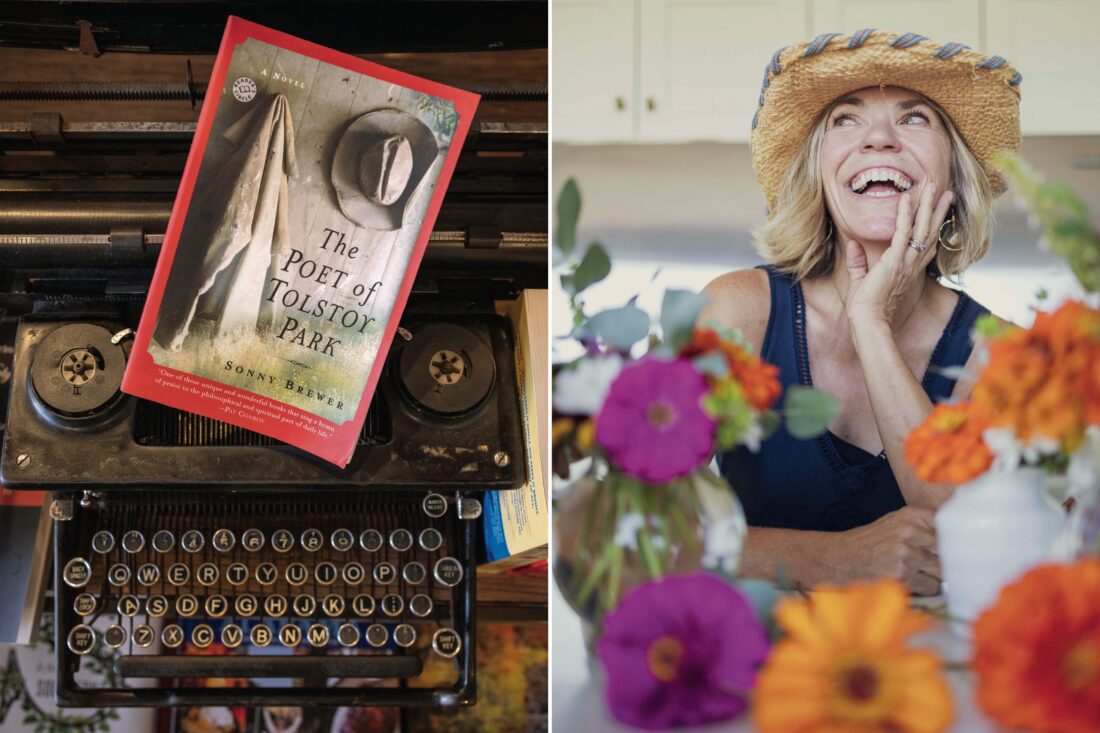

After driving in the final nail, Sonny was on his way to a real estate course (Butterworth’s advice for income and time to write). “I drove into this parking lot to attend class,” Sonny told me. “I saw this round house, and I thought, Oh my God, what is THAT?!” A concrete dome with knee-high windows, built at the foot of a gnarled live oak, it looked to him “like a hobbit house or something from a movie set.” What was this non sequitur in the middle of an office parking lot? That question set him on an almost twenty-year journey that resulted in his first book, a beloved tome of Fairhope historical fiction called The Poet of Tolstoy Park.

Before boarding my plane in Idaho, I’d called Page and Palette—one of the South’s best bookshops and a social hub of the town—to ask what I should read to ease into the Fairhope state of mind. Poet was their pick. Rick Bragg, my friend and mentor, narrated the audiobook version I downloaded, and his Alabama accent was a warm bath for my troubled mind. Coincidentally, the book begins in Nampa, Idaho—twenty miles from my house in Boise—where a real-life Idahoan named Henry Stuart was diagnosed with tuberculosis in the 1920s. His doctor gave him a year to live and advised that dying from consumption would be less miserable in a warmer clime. He boarded a train to Fairhope, where he built a tiny round house in the woods on property he named Tolstoy Park. His domicile stood unchanged as a town grew around it.

A century after Henry did, I was traveling to Fairhope to recover from birthing my latest book, a true saga about a famous child abduction and murder. I needed to read some fiction and fish my way out of a postpartum funk. Five years had passed since I moved my life from Alabama to Idaho. I longed to marinate in Southern salt water, to stick my head in some brackish bay and hear the crackle of sea life. Eighty miles from the Florida bayou where I was raised by a meat-pole fisherman, Fairhope feels like where I’m from.

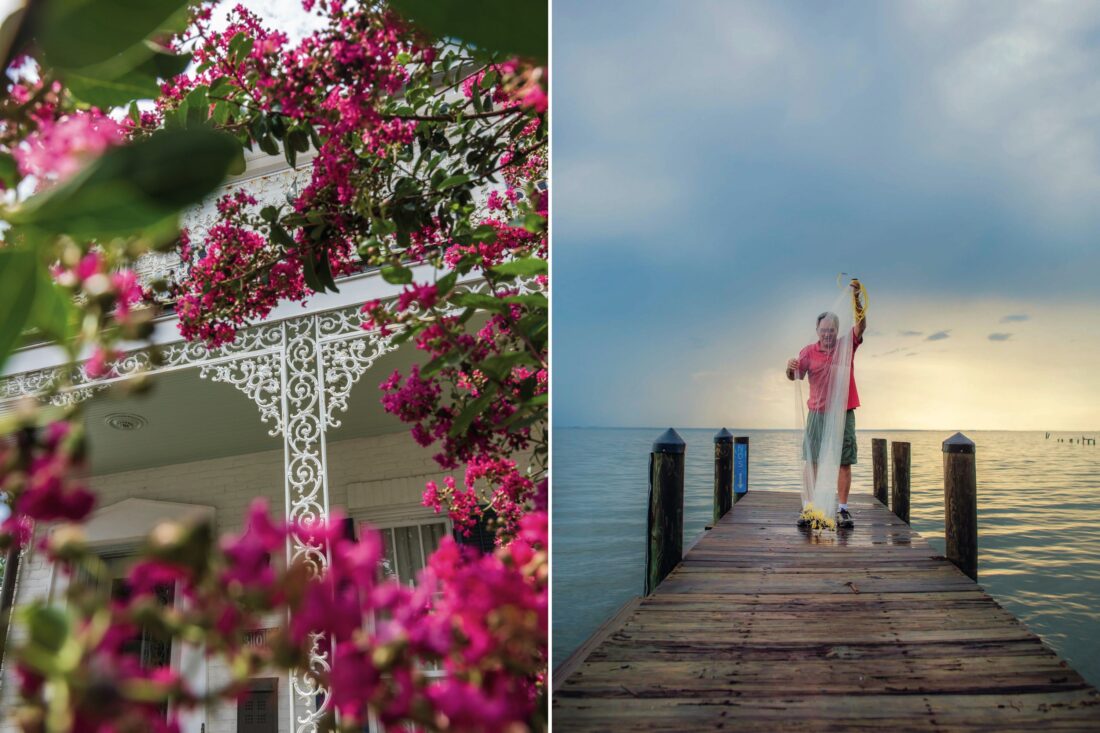

The classic resort in Fairhope is the Grand Hotel, with its golf course, dining spots aplenty, and spa. But I was drawn to the waterfront views of a boutique inn called Jubilee Suites. Housed in a World War II–era Mobile building moved to Fairhope in 1947, it has fountains and wrought-iron railings and balconies that reminded me of New Orleans. Paddleboards sit ready on its bayside beach.

I arrived on a stormy night and relished the echoes of my Southern childhood. Lifting the hem of my dress, I walked barefoot in the rain, mud squishing through my toes, listening to the symphony of a thunderstorm. Cicadas, katydids, spring peepers, and crickets sang their chorus from the dripping pines, and fat raindrops beat a percussion on the magnolia leaves.

The next morning, I had plans to fish with Bo Meador, who learned to swing a fly rod around the same time he mastered walking. Compared with wading in trout streams, he said saltwater fly fishing would be more “like hunting and fishing.” But on the morning of our trip, twenty-knot winds derailed that dream. Bo offered to just cruise me around in the Gulf near Dauphin Island. “We won’t catch fish,” he said. “But at least you’ll have a boat ride.”

As Bo foretold, we sighted no catchable fish. Determined to go fishing if not catching, I practiced casting at mullet. Vegetarians that will not eat a fly, they sufficed as moving targets. But the wind, the pitching boat, and the sinking line turned my casting into crochet. He dropped me back on Dauphin Island, and I drove my car onto the ferry to sail back across Mobile Bay, marveling at its vastness. That evening, sipping wine on my balcony, I watched the sun melt into the water.

I awoke to whitecaps—more un-fishy weather. I drafted plan B over oatmeal cake, Conecuh sausage, and slabs of local Bill-E’s bacon, thick and smoky enough to satisfy even a Benton’s devotee. I chatted with Christy Wells-Fritz, who tends the inn’s lush gardens, and she mentioned she was a musician from California wine country. “Ever play with Roy Rogers?” I asked. One of the finest slide guitarists of his time (yes, he’s named after the cowboy actor), he’s the only California musician I’ve ever met.

“I used to open for him all the time!”

“His wife is a character in my next book,” I said, smiling at Fairhope’s magic.

“What’s your book about?”

“The kidnapping of Polly Klaas.”

“I was there when that happened. I wrote a song about it!” Plucking a guitar off the wall, she sang themes at the heart of my new book, In Light of All Darkness, pausing to recall the lyrics she had penned three decades earlier.

After breakfast, I went to meet Bo’s father, Jimbo Meador, a pioneer of saltwater fly fishing. If I couldn’t fish, at least I could hear some fish tales. Jimbo is a local legend who inspired, at least in part, the character of Forrest Gump. The late Alabama author Winston Groom named him on the dedication page of the book, and Tom Hanks’s dialect coach taped his voice. He was a gray-bearded jogger in the 1970s, “a time when if you was runnin’, people thought you’d done somethin’ wrong,” and made a living on shrimp boats, tugboats, fishing boats, and a custom aluminum boat he used to give tours of the Delta.

I asked permission to record him. He laughed. “Can you speed that thang up?” Jimbo told me about Mobile Bay’s famous Jubilee, a phenomenon that occurs when low dissolved oxygen drives flounder, shrimp, crab, and eels onto shore, where they’re gathered up like Easter eggs. He spoke of frogging, catching soft-shell crabs, and landing mighty jack crevalle in hour-long fights with a fly rod. He’s retired from giving Delta tours, but he says the journalist Ben Raines has picked up the torch through his ecotour company, America’s Amazon Adventures.

For lunch, I met Sonny, a vegetarian, at the Sunflower Café, next to a health food store. “Rick refuses to eat here,” he said of our mutual friend. For the culinary record, Rick told me he prefers the fried chicken and pineapple upside-down cake at Saraceno’s, the beignets at Panini Pete’s, and the gravy biscuits with sliced tomatoes at Julwin’s. I always trust his food picks, but after the previous night’s supper of fried snapper throats at Sunset Pointe, I needed me some sprouts. Over vegan mushroom bisque and a mandarin orange salad with blackened shrimp, Sonny and I talked about how some stories choose us—not the other way around. These stories decide what they’re really about and refuse to be written before they are ready. In Light of All Darkness had to incubate for seven years. The Poet of Tolstoy Park took almost twenty.

Sonny drove us to the round house and pointed out tiny footprints in the concrete. Those inspired Anna Pearl, a fictional child in his novel. The nonfictional Henry Stuart labored for 381 days to build this strange abode, scratching the date of workdays into bricks—a storyline etched in the earth. Stuart outlasted the doctor’s predictions and lived another twenty years. Sonny is always asked why. “I think it’s because he left his boots on the train and walked barefoot in the Fairhope dirt.”

Underneath Fairhope’s art galleries, wine bars, and boutiques, Sonny swears, there’s some kind of literary magic in the soil, which may account for Henry Stuart’s longevity and might, if you love a good yarn, explain “a town with more writers than readers.” Nowhere is this more evident than in Page and Palette, a bookshop that’s been in the same family for three generations, with shelves filled with works by authors who have lived or written in Fairhope. “Mark Childress lived here,” Sonny said. “Jimmy Buffett had a place near here. Judith Richards. Suzanne Hudson. Joe Formichella. Tom Franklin. Beth Ann Fennelly. Fannie Flagg. On and on.” We grabbed a table at the Book Cellar, the bookshop’s watering hole, where you can sip a Tequila Mockingbird and listen to a reading or a bluegrass band, and I realized why Rick calls this place “the turnstile of the town.”

For dinner at the Hope Farm just up the road, we met the younger half of the father-son team who envisioned this hydroponic farm-to-table restaurant. Bentley Evans (named not after the car but the doctor who saved his sister’s life) gave us a tour of the pocket-sized urban farm that embodies their “fair hope” for a sustainable future. In raised beds, an orchard, and shipping containers equipped with a hydroponic system that cuts water use, they grow everything from oyster mushrooms to Queen of the Night tomatoes, seemingly all of which made its way to our plates.

Over Gulf snapper stuffed with crawfish and mushroom toast with aged fontina, I told Sonny I’d come to Fairhope to fish my mind off writing, only to find myself tangled in story threads. The storytellers of Fairhope were everywhere, winking from the woodwork. In the books on my hotel nightstand, and in a songwriter’s lyrics. Underfoot on the sidewalk by Page and Palette, where Winston Groom scratched his signature. In Jimbo Meador’s unforgettable voice, and in his son’s sense of adventure. In “Rick Bragg’s ‘Ode to Grouper’ Sandwich” at Sunset Pointe, inspired by a requiem he wrote for this very magazine. Henry Stuart enjoyed quoting Emerson on “the intoxication of travel,” Sonny told me. But in Sonny’s words, “No matter where you go, you find no one other than yourself and all of your ghosts there waiting to greet you.”

Garden & Gun has affiliate partnerships and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a product. All products are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.