Duke University’s Cameron Indoor Stadium may blend seamlessly with the rest of the Gothic architecture on the Durham, North Carolina, campus, but among basketball faithful, it’s a standout. With only 9,314 seats, Cameron has sold out every home game since 1990. Students camp outside the arena for weeks to get tickets. Painted-up Cameron Crazies pack shoulder to shoulder on the bleachers, causing the room to vibrate.

“The fans are right on top of the players,” says Lewis Bowling, a Durham-based writer and Duke sports historian. “In press row, you can feel your body move up and down because the Cameron Crazies are stamping their feet right behind you. The stadium is so intimate players can look around the court and see the faces of the fans.”

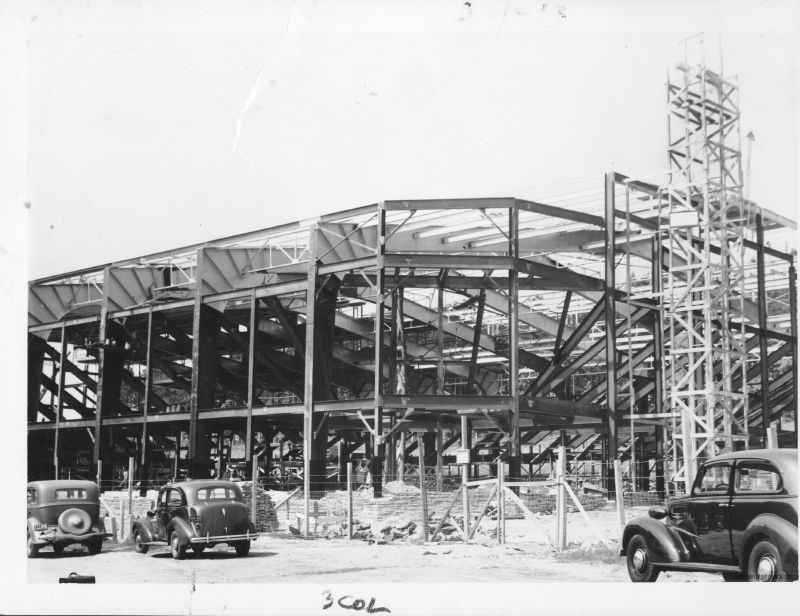

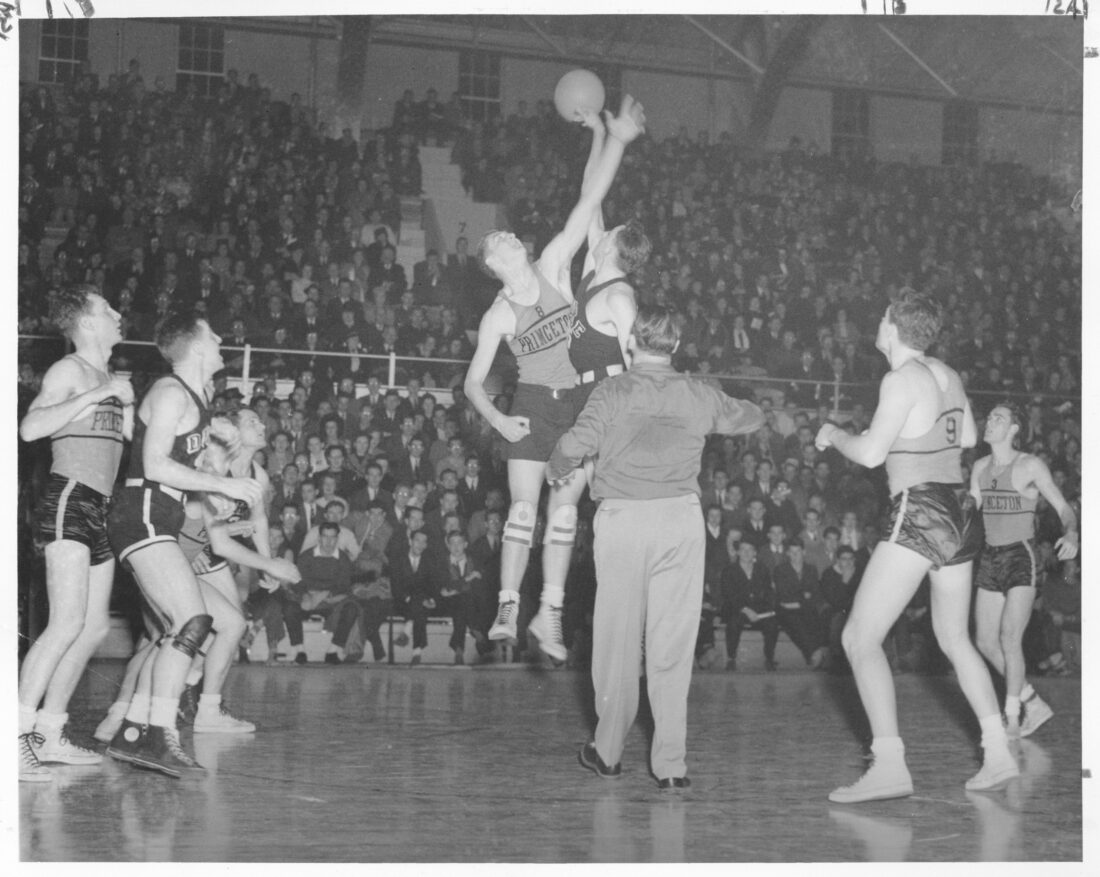

Construction started in April 1939 and lasted nine months, costing the school $400,000 (almost $9 million today). The stadium opened in January 1940 for a matchup against Princeton (which Duke won 36–27), and in the eighty-four seasons since, it has become a bucket-list venue for basketball lovers across the country.

Here are five reasons the stadium deserves its place in college sports lore.

1. The building’s initial design was conceived on the back of a matchbox—probably.

In the 1930s, the Duke men’s basketball program was gaining steam: They’d won a few conference titles here and there and were building a steady following under the leadership of head coach Eddie Cameron. At the time, the team played in Card Gym, a 2,500-seater that still stands some twenty feet away from Cameron. “It could maybe fit three thousand people if you stuffed them in. I’ve seen pictures of fans sitting up in rafters with legs hanging down,” Bowling says. “They were selling out the gym at that time, which is where the need for the new gym came from.”

Legend holds that in 1935, Wallace Wade, the then-football coach and athletic director, and Eddie Cameron scribbled their ideas for a new stadium on the back of a matchbook. For what it’s worth, that matchbox has never been found.

2. Cameron would not exist without the Duke football team.

Basketball may reign supreme these days on Tobacco Road, but when Wade and Cameron first conceived Duke Indoor Stadium, the university was considered a football school. Wade had left the University of Alabama after the 1930 season to coach the Blue Devils, and during his sixteen-year tenure in Durham, he led the team to seven Southern Conference championships and two Rose Bowls. “Wade agreed that the 1939 Rose Bowl proceeds would be the money to start the building of Cameron Indoor,” Bowling says. “And the 1942 Rose Bowl and 1945 Sugar Bowl pretty much paid the mortgage.”

And while Duke basketball was beginning to blossom in the 1930s, no one could have foreseen where the program would end up. William P. Few, the then-president of the university, said of the plans to build Cameron Indoor: “With the new gymnasium, basketball might make a moderate yield if the people are willing to pay a reasonable admission fee.”

Bowling laughs. “I would say they accomplished that.”

3. A Black architect designed the building more than three decades before C.B. Claiborne would integrate the Duke basketball team.

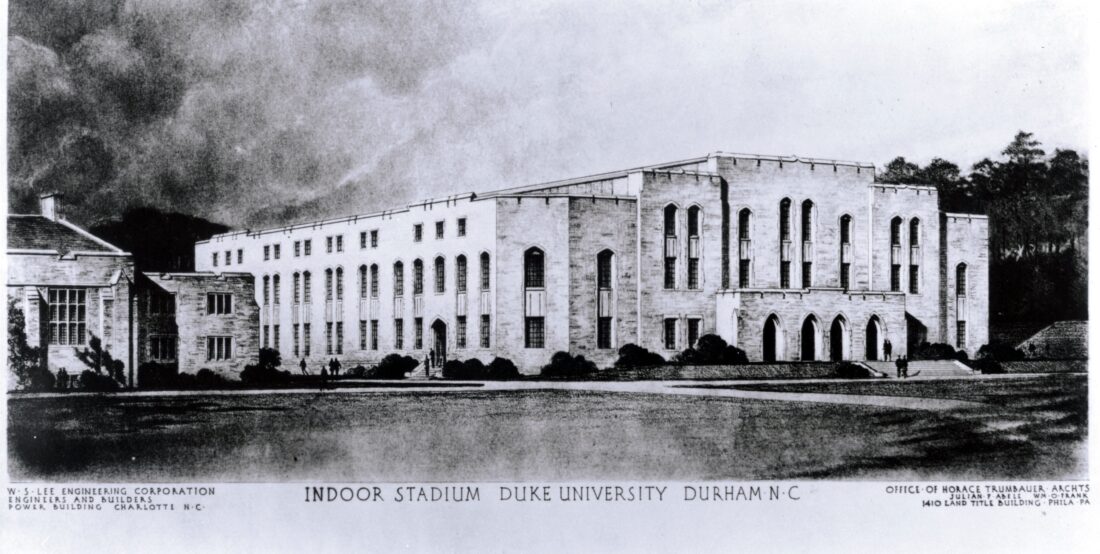

For the project, Duke administration tapped the Philadelphia architect Horace Trumbauer, whose firm had designed the majority of West Campus, including Duke Chapel. “Hence the stadium uses on the exterior that same distinctive stone from a nearby quarry,” says John Roth, a producer for Duke sports media and editor of GoDuke magazine.

But the real mastermind of the project, who fully took it over after Trumbauer’s death in 1938, was Trumbauer’s chief designer, Julian Abele. Abele studied architecture at the University of Pennsylvania before attending the École des Beaux Arts in Paris, becoming one of the first Black architects in the United States. In the midst of segregation, Abele signed his sketches for Duke Indoor Stadium, firmly cementing his place in American history.

4. One of the smallest Division I basketball arenas in the country today, Cameron Indoor was almost even smaller.

Abele, Trumbauer, and their team initially pitched a smaller gym that would have accommodated around five thousand spectators, a figure the architects already considered too large. Trumbauer wrote a letter to president Few saying: “For your information Yale has in its new gymnasium a basket ball (sic) court with settings (sic) for 1,600…I think the settings for 8,000 people is rather liberal.”

But Wade, Cameron, and the rest of the Duke athletic department pushed for their vision of a landmark venue. “At the time, it was the biggest arena in the U.S. south of Philadelphia’s Palestra,” Roth says. “When it opened to a crowd of eight thousand for the Princeton game in 1940, that was the largest audience ever to watch a basketball game in the South.”

5. It’s proof that bigger is not better.

A renovation in the late 1980s remodeled the concourse and added 750 seats. And while improvements have been made in years since—a new floor in 1997, air conditioning in 2001, a new lobby and hospitality space in 2016—more substantive changes to the gym itself are unlikely. “During the renovation in the eighties, they were looking over at Chapel Hill at the Dean Dome, which holds almost twenty-two thousand people,” Bowling says. “They’ve thought about expanding and making it bigger. But everyone—even Coach K—said let’s keep it like it is. It’s so intimate, and that’s what makes it one of the most revered arenas in the country.”

Caroline Sanders Clements is the senior editor at Garden & Gun and oversees the magazine’s annual Made in the South Awards. Since joining G&G’s editorial team in 2017, the Athens, Georgia, native has written and edited stories about artists, architects, historians, musicians, tomato farmers, James Beard Award winners, and one mixed martial artist. She lives in North Charleston, South Carolina, with her husband, Sam, and dog, Bucket.