The Foothills Parkway, a scenic two-lane that hugs the forested slopes of East Tennessee overlooking the Great Smoky Mountain National Park, has remained unfinished for decades. But this weekend, it’s sixteen miles closer to completion. On Saturday, November 10, a stretch of the parkway between Walland and Wears Valley that includes a 1.65-mile portion known as the “missing link” finally opens to motorists.

The story of the parkway begins in 1944, when Congress approved building a seventy-two-mile road that would stretch from Interstate 40 in the east, snake around the northern and western edges of the park, and end at Chilhowee Lake in the west. It was inspired by the Blue Ridge Parkway, which links the North Carolina side of the Smokies with Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. “The premise of the parkway was for it to be a scenic roadway that, by design, would allow spectacular views into the national park,” says Alan Sumeriski, who, as the park’s chief of facility management, has overseen this phase of the project’s construction.

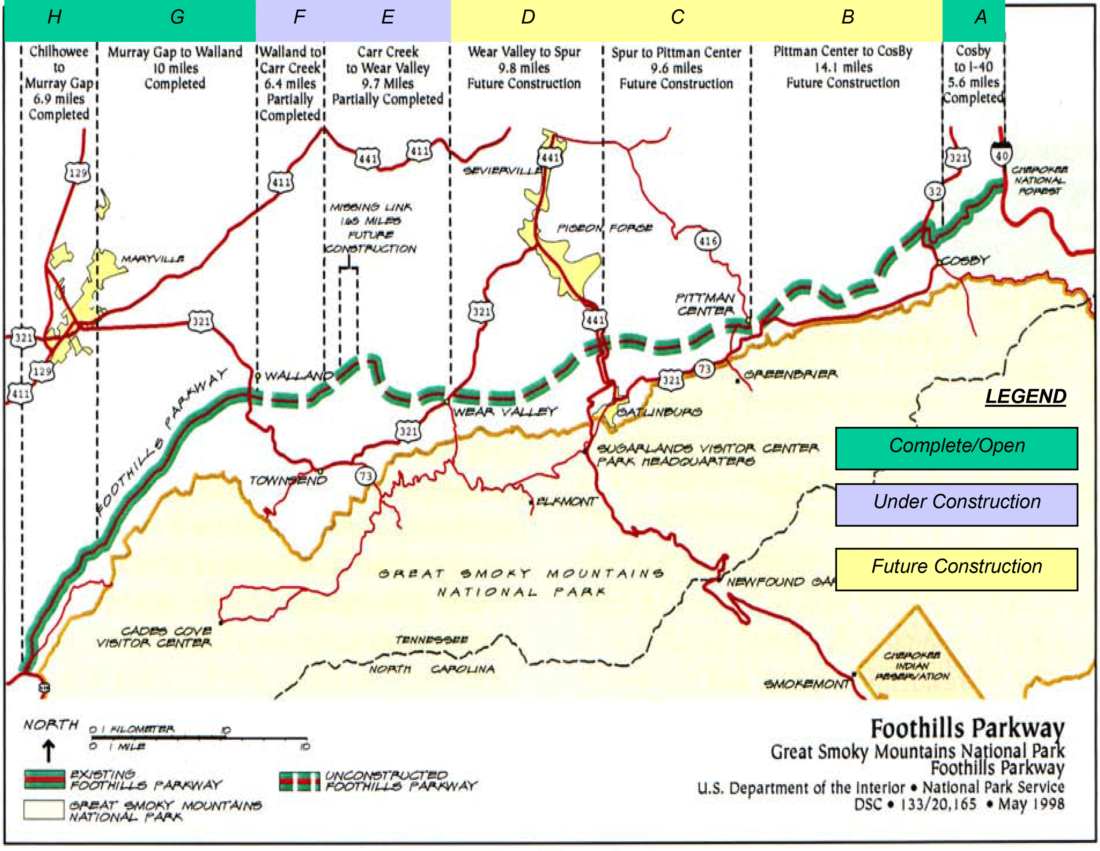

Sections E and F comprise the 16 miles opening this weekend.

The first of eight total sections of the parkway—sixteen miles on the far western end and six miles on the far eastern end—were completed in the late 1960s. Around that time, construction began on the western segment that connected Walland, now home to the famous Blackberry Farm resort, to Wears Valley. “But there was limited funding due to competing needs,” Sumeriski says. “Then, in 1986, one of the retaining walls fell, which put a pause on the project altogether.”

When building resumed in the 1990s, nine gaps in the road needed to be connected. “The question arose: Do we build bridges or cut-and-fill to connect the ‘missing link?’ What environmental risks do we have here?” Sumeriski says. The Park Service chose to build bridges, a more environmentally sensitive approach. (Both water and wildlife can pass beneath.) Construction continued to move slowly, though, until 2009 when the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act passed, providing funds to propel the project forward.

Photo: National Park Service

One of nine newly completed bridges.

“When we construct a road, we try to fit it into the landscape,” Sumeriski says. “This leads to engineering challenges, but it also leads to creativity and intriguing architecture.” Take Bridge Two, for example, which is similar in design to the serpentine Linn Cove Viaduct outside of Linville, North Carolina, on the Blue Ridge Parkway. Except that Bridge Two increases more than seventy feet in elevation in less than 800 feet in length—a nearly ten percent grade. “Bridge Two has won three different awards within the bridge industry,” Sumeriski says. “It was built in Strawberry Plains, Tennessee, shipped on site, and set with a crane.” After Bridge Two’s completion, the last five of the nine bridges were built in place using top-down construction, a method where equipment works from above, limiting the construction site’s impact on the environment.

“[The view] from this part of the parkway is a view that no one has ever painted or photographed before,” Sumeriski says. And now, an estimated 3,000 visitors per day will be able to enjoy it.

Caroline Sanders Clements is the senior editor at Garden & Gun and oversees the magazine’s annual Made in the South Awards. Since joining G&G’s editorial team in 2017, the Athens, Georgia, native has written and edited stories about artists, architects, historians, musicians, tomato farmers, James Beard Award winners, and one mixed martial artist. She lives in North Charleston, South Carolina, with her husband, Sam, and dog, Bucket.