Brandon Gaudin got his dream job this past February, when his phone rang one evening on the west side of Atlanta while he was eating queso dip at Taqueria del Sol. The man on the other end of the line, an executive at Bally Sports, was calling to offer him the gig to become the television voice of the Atlanta Braves, vacant after Chip Caray left for the St. Louis Cardinals. Gaudin didn’t exactly know how to answer, though he already knew the answer—he’d been fantasizing about such an improbable response for almost thirty years. “I remember when I picked up and he said, The position is yours if you’d like it, and it just took me a moment,” Gaudin says. “Truly, there were a couple seconds there where I just didn’t reply. It kind of all hit me. Oh my goodness, dreaming about this for almost three decades, and now here we are.”

Gaudin, thirty-nine, from Evansville, Indiana, has been a Braves fan since he was seven years old, indeed was inspired to become a broadcaster by watching games on TBS. His professional career out of college at Butler began by calling play-by-play for rookie-league baseball in Utah for $500 a month; then he became the voice of his hometown Evansville Purple Aces D-I basketball team; then he was behind the mic as Brad Stevens took Butler to the second of two Final Fours. He was hired by Georgia Tech and moved to Atlanta ten years ago, and shortly thereafter made the national stage, calling NFL and MLB and college football and basketball games. Gaudin is also the voice of the Madden NFL series, and he has a personal studio in his house so he can record his lines for the video games. He lives in Buckhead, frequents Henri’s Bakery and Souper Jenny, and drives to the stadium to work.

This is your dream job. Hardly anyone ever gets their dream job. You’ve barely had it for three months, but…what’s that like?

There have been a lot of pinch-me moments, if you will. The first one came when I got the call that they’re offering the position. And I remember picking that call up—we were out to dinner late, it was around 8 o’clock. An unknown 404 area code number came in, and I thought, Well, this is probably it, one way or the other. And the next one was opening day. When I sat up in the booth for the Braves and Nationals. Getting ready to go on the air for the first time, and I was just flooded with thoughts of my childhood.

When you went into the Truist Park booth for the first time, what did you see? Did you personalize your work area?

The first thing that struck me, there are pictures. You open up the door to that booth, there’s a picture there of Skip Caray. And there’s nobody that had a bigger influence on my career. That’s who I listened to, from age seven until he stopped doing the job. From then until the end of my high-school career, I watched him so much, and I studied him so much; that’s the first face you see. Even though it’s just a picture on a wall, since he’s passed.

I sat down in the chair. I got there early. I was probably there at 3:30 for a 7:20 first pitch. The stadium is empty. There are a few ushers out there. I set my scorebook down; I set my laptop down. I sat there in the booth, with nobody else in there, and just soaked it in for a while. I was gonna get there early, regardless. But especially with the impact of this job on me, I knew I wanted to make sure I was the first one there, and just have a little moment to myself.

How did you become a Braves fan in Evansville, Indiana? That’s Cardinals/Reds/Cubs territory.

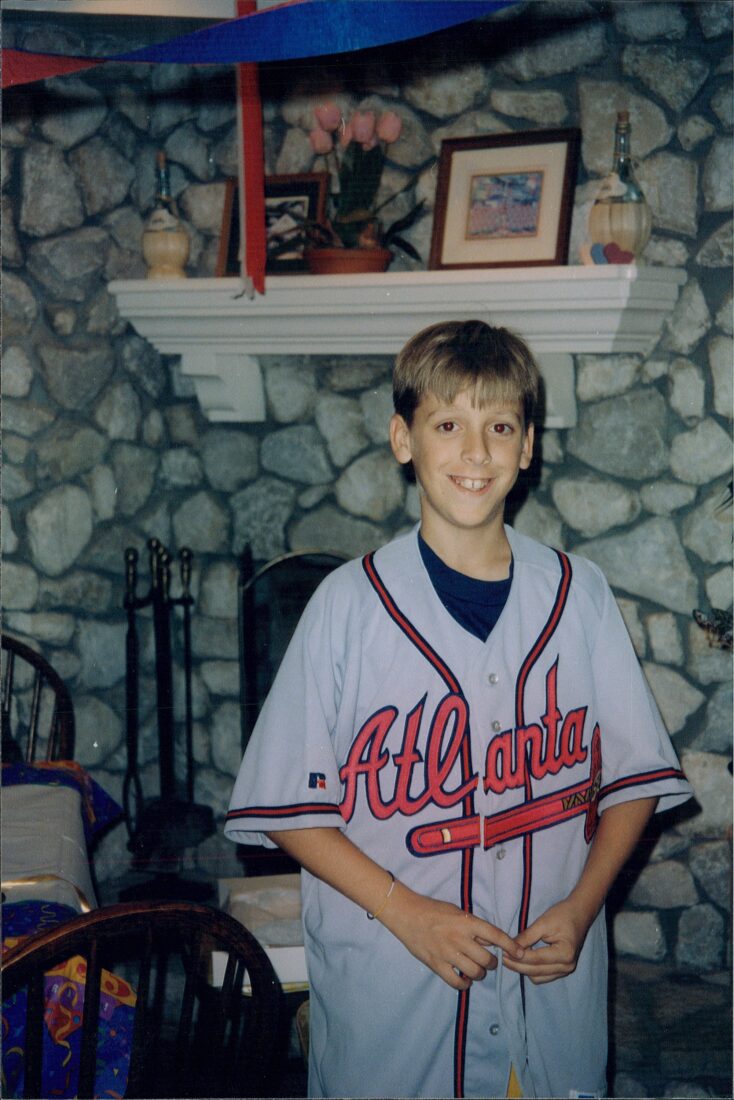

I’m a TBS Superstation kid of the nineties. In 1991 I was seven, and my mom has a brother who lives in Atlanta, my uncle Mike. And they had tickets to game five of the 1991 World Series. They invited our family down. That was the first professional sporting event I attended. I can remember vividly walking into Fulton County Stadium back then. The Braves won 14–5. I remember several plays like it was yesterday. I remember Mark Lemke’s triple with the bases loaded to bust the game open in the seventh inning. I remember holding my foam tomahawk as we were leaving the stadium and getting into my uncle’s car, holding it out the window on our drive home. From that moment forward I was hooked on Braves baseball. And through the nineties, you know, they aired on TBS. From that point forward I watched them religiously every night. In 1992 and 1995 (when they won it all), we came back down for the World Series.

So it was kind of a combination of the ability to come down to the games and watching nightly on TV, and I just started to listen to Skip, Joe, Don, and Pete and really became enamored with their commentary. That not only fostered my love for Braves baseball, but fostered my love for sports broadcasting. From the early nineties on, anyone that knew me, my friends and family, really anyone in Evansville, they knew I wanted to be the Braves broadcaster. That was always a part of my story.

Speaking of Skip Caray: He responded to a letter you wrote him as a kid, encouraging you to become an announcer. He even sent it back to you on official Turner Sports letterhead—you tweeted about it. You still have the letter. Do you have it framed somewhere?

I don’t have it framed but I’ve always had it in the envelope. I’ve got it here with me now. And a lot of people have asked, wait, how do you have the original letter you wrote him? And I thank Skip for that because he had the foresight, or for whatever reason, he put my original letter back in the envelope with his reply to me. I have both of them. And they’re obviously such treasured mementos. They’ve meant a great deal for the last thirty years, and now they mean even more. I remember holding the letter for the first time after getting the job, and re-reading it. It was an emotional moment. This letter you wrote when you were thirteen to your childhood broadcasting idol, the reason you got into this business, who’s now passed. I remember checking the mailbox every day after I wrote to him, and I remember seeing the Turner Sports letterhead, and I came in and showed my mom and dad and opened it up and read it. He was this figure on television, this voice I was trying to emulate. And when I saw he had written me a note, it made him human. It pushed me even more.

I knew I wanted to try broadcasting, but I was still so young I didn’t know how to do it. Well he told me in that letter to tape yourself, and go back and critique yourself. And I had a little hand-held recorder and I started to do that. I would mute the Braves games in our living room and I would go back and listen, and I hated hearing my own voice, but that was kind of the springboard for me getting my first job. It was unpaid, but I was calling my high school baseball games on the radio. So that letter, it wasn’t just a letter—it had a profound impact and kind of pushed me knowing that, hey, Skip took the time to do this.

You’re essentially taking over the Braves from the bloodline of that single family. Another Caray isn’t stepping into the booth—you’re the guy.

I understand that intimately, given how long I’ve watched Skip and Chip for the last three plus decades. It is daunting and it’s a lot to take in when I realize that nobody except the last name Caray has been the lead play-by-play announcer for such a long time. And I can’t be them. They are their own voices and their own family and such icons. Those are such big shoes to fill that you realize you can’t fill them. You realize you have to get your own shoes and try to stay true to yourself and do what you think is best on the broadcast, through your lens. I’m not a Caray, I’m not going to be a Caray; that’s a legacy they left that’s always going to be a part of Braves baseball.

Traveling with the players, being on the field, having to talk about them during 140 games—what is it like to try and get to know a baseball team?

I’d say it’s like you’re peeling layers off an onion. I want to fast-forward the process, if I’m being honest. To where I have meaningful relationships with the players and the staff. That’s starting to happen but it’s going to take time. There are so many people in the travel party and on the plane and at the hotel, I’m just now beginning to scratch the surface of being able to have conversations with people and get to know their story. I would like to expedite that process, because I think once you get to know people on a deeper level, there’s a trust there, and then they begin to know they can say things to you. And they know if it’s something sensitive, you’re not going to say it on air, but then that also brings out the good stuff you can say on air. Like a good story or an interesting nugget about their background. I’m only here in month three being around the team on a regular basis, and so those relationships are about to be built, but it’s going to take time to get them to the point where there’s a comfort level.

You live in Buckhead. What is your routine now?

I drive to the games. I get on West Paces and take it over to Northside and up. It’s fifteen minutes, traffic pending. Jeff Francoeur and I park in the Orange lot right across from the stadium. I walk in, head up the elevator, walk across the concourse, and what I’m starting to do and what I think I’ll continue to do is, I like to get there (most home games are at 7:20) around 4, so that I can quickly set up my stuff, write in my lineup card, and then take the elevator down and go out on the field for batting practice. Because when you cover a specific team, you need to start integrating new stories and nuggets in throughout the season. Because the fans watching are so educated on these players that you can’t just recycle the same few biography notes on all these guys. That’s okay to a degree, but at some point, they want you to go deeper, you know? They want to know what was said at batting practice. They want to know about your conversation with Brian Snitker or Austin Riley…Then I’ll hop on the headset and talk to our producer and just go over all of the elements we’re going to have on the broadcast. The sales elements, the promotional reads that I have to go through, and then we do a rehearsal for our on-air open, the first thing you see when we come on air—we rehearse that about forty-five minutes before first pitch. And then you just kind of get your final notes, a quick PowerBar and put the headset on and off you go. That’s the cadence I’ve settled into thus far.

You’re a Hoosier, but do you also consider yourself an Atlantan now?

Fifty percent of my time in Atlanta is on a Delta jet leaving from Hartsfield-Jackson. Well now I don’t get any more Delta SkyMiles because the team charters flights (laughs). I mentioned my mom’s brother, Mike, still lives down here. My uncle Mike and my aunt, they’ve got two kids. Growing up, we were far away and didn’t see them much. But they have been a great stability for me since I’ve been in this city. I always get together on Sundays with them for dinner. And I play basketball all the time with my cousin Jake. They have helped establish roots here for me. Having family here, and people that know and love this community, has expedited my process in doing the same. Atlanta’s become home. Hartsfield-Jackson is a second home to me. Henri’s is right across the street from me, that’s an Atlanta staple. I go there frequently. I go to OK Café a lot. I eat at strange hours—I’ll go to OK Café twenty minutes before they close and sit down and get either the egg salad sandwich with soup or the veggie plate with cornbread. I can pretty much guarantee you that over the last ten years, I’ve sat at every table in that restaurant.