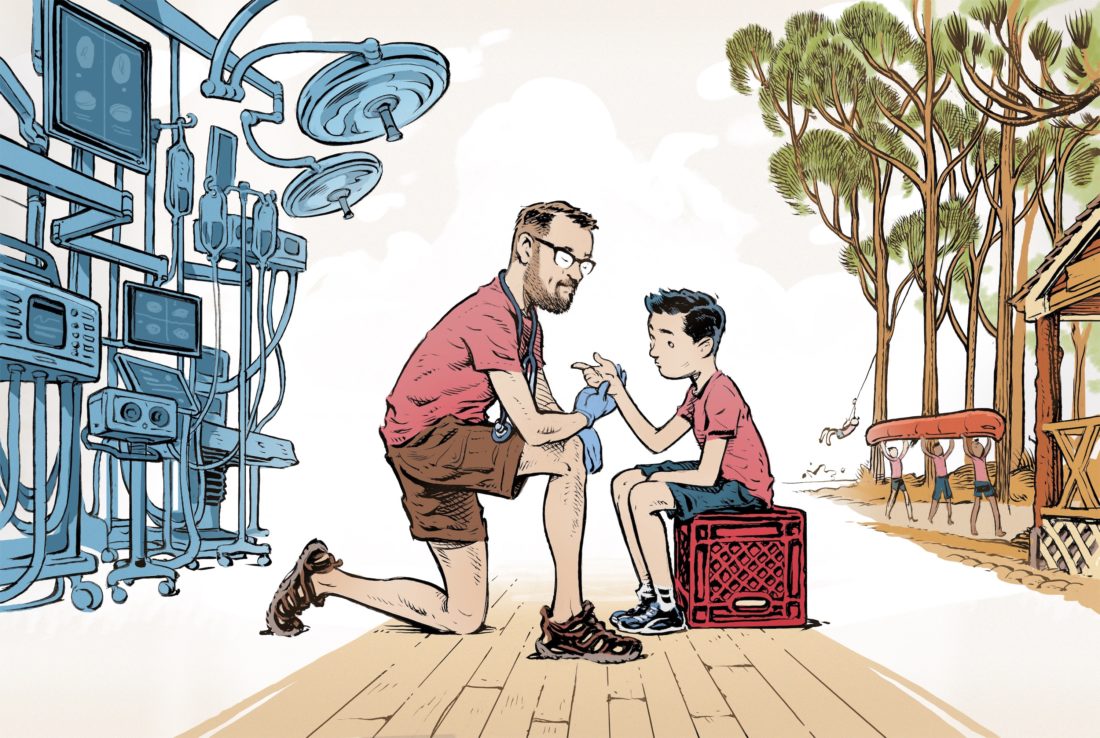

I sat at a worn wooden desk under fluorescent lights in the seventy-year-old cabin that serves as the infirmary of a boys’ camp on Lookout Mountain at the junction of Alabama, Tennessee, and Georgia. Cabinets full of medicine, bandages of all sizes, glucose monitors, and asthma nebulizers, and drawers of EpiPens lined the room. The chairs were mix and match, the footstools upturned milk crates, the wooden floors slanted just a bit, but all of it was clean and organized and ready for nearly anything after years and years of nurses and doctors running the space, ready for whatever camp could throw at them.

The week before, the camp owner, a friend, had called to ask if I would serve as the camp doctor for the weekend. She knew that I was coming to the camp’s annual father-son weekend with my son, who had finished his final term as a camper the previous summer and who was going to work as a kitchen server. My plan was to stay in one of the cabins to write and maybe canoe or bike ride with him on his breaks between meals. The year before, he and I had paddled farther down the Little River than I had when I was a camper years back, and we had raced to make it back to dinner. The riflery and archery huts were exactly the same as they were forty years ago. Now a new climbing barn entertained the boys, and I could walk among the pine trees along the trails next to the river. I loved this camp. It was a part of my past and an important part of my son’s life too.

“Thank you so much,” she said when I accepted. “Our scheduled doctor had to cancel, but there will be one of our very best longtime camp nurses there. I can’t imagine that you will have anything to do. You can wander around and the nurse will call you on the radio when she needs you.”

Even though primary care is way outside of my specialty of twenty-five years—pediatric neurosurgery—it sounded fine with an experienced nurse in front of me to diagnose and treat the routine things seen at a summer camp. I had a few friends who had done it in the past. Besides the occasional broken arm or anaphylaxis after a bee sting, it sounded low stress. Anything too big, and down the mountain the camper would go to the local emergency room. After a busy week and looking at another one to come, I was looking forward to taking a bit of a break.

As the camp weekend approached, I found myself squarely within my element as my fellow and I took out a brain tumor the size of a mandarin orange that had grown out of a two-year-old girl’s brain stem. It had gotten so large that it was pushing the brain stem over to the side and had wrapped itself around several critical blood vessels and cranial nerves. The effect of the direct pressure on the brain and the subsequent blockage of normal cerebrospinal fluid pathways through and around the brain was beginning to take its toll on her.

Over the month prior, the child’s parents had become increasingly concerned as she vomited more frequently and became intermittently lethargic. Multiple visits to the doctor and emergency departments ensued. Viral gastroenteritis? Perhaps a severe ear infection? They can cause similar symptoms. At first, medicine did seem to help. Everyone’s concern calmed down. But over time, the vomiting returned.

Frantic, knowing something was just not right, the parents called their primary care doctor’s office and begged for help. It was an astute child neurologist they were quickly referred to who ordered the urgent scan. When I walked into the room to talk to the parents, they were shell-shocked. “We saw so many people,” the girl’s mom said. “How did a brain tumor get missed?” She buried her head in her hands. “What else could we have done?”

The truth is that nobody is thinking brain tumor when a child first presents with vomiting or lethargy or headache. These are all very common symptoms for many pediatric medical issues. It’s only when they persist, worsening despite any action, that it becomes clearer that a brain MRI to look for something more sinister is the next logical step. When I spoke to the family, I gently tried to reduce the frustration about this idea of a missed diagnosis. This is how these cases always present, I explained, with these symptoms worsening over time.

We took out her tumor in an eight-hour operation that Thursday night, carefully dissecting the tumor away from each of the enveloped cranial nerves and taking it just up to but not into the all-important brain stem. Time became less important, and the work absorbed us. Her vital signs and nerve monitoring had remained stable, and I was cautiously hopeful and a bit elated as I often am in these moments just after surgery.

After I scrubbed out around 9:00 p.m., I looked at my phone. The camp director had texted while I was operating. It turns out the longtime camp nurse had a last-minute family conflict. Could I still come but do both roles? The nurse would be there when I arrived, give me a tour of the infirmary, and leave me on my own.

I stood in the operating room with my loupes and headlight still on, my fellow finishing up the skin closure. I thought about how this weekend had somehow morphed from a relaxing getaway with my son into a role that I had last entertained well over thirty years ago when I started medical school. Back then, I had seen myself becoming something like a country doctor, even making house calls and delivering babies if I had to—Mabel, boil some towels. This here baby’s a-comin’—the same way the doctor I shadowed in my small Mississippi hometown had done.

Then gradually came the early weekend mornings in the anatomy lab, teasing out the brachial plexus, the allure of the human brain and nervous system calling to me. Hour upon hour in the neurosurgical OR grew into a call that I was unable to ignore. I laid those early dreams at the foot of the all-consuming altar of neurosurgery and walked into my future.

But right then was not the time to think about any of that. There was an important conversation with the parents yet to come. Our patient awoke after surgery wiggling her fingers and toes to great excitement all around. In the family sleep room, I sat with her parents to explain what we had done over the past several hours, what to expect as she gradually woke up, and the importance of her MRI the next day. In the past few years, I have stopped feeling that there should be some impenetrable barrier between surgeon and parent, that somehow I must completely gather myself back up in suit and tie and look superhuman after laser-focusing on the child for hours. I have come to see it now as one human being sitting with another. One tired from working hard but who will, when the work is done, go home. The other’s journey, however, just beginning. That shared connection between helper and helped is one of the aspects of medicine that I find makes us essentially human, and I find, as both one who has helped and one who has been helped, that the connection in that moment is like no other.

The following day, the patient’s postoperative MRI looked clean of any substantial residual tumor, and I made it out of the hospital by midafternoon so that my son and I could begin our journey to camp. He is now old enough to drive, a milestone achieved nearly a year ago here in Tennessee, and because I was tired and he had made the same drive months before with my wife, I felt comfortable to let my mind consider the next couple of days while he drove.

I thought about how the last time I was in that same infirmary, forty years ago, I was a camper myself, getting a shot of straight epinephrine (those were the days before EpiPens) after I rode a horse knowing full well I was allergic to them. I also remembered, as a first-year camper, vomiting the hot dogs we had eaten around a campfire. At some point before my heaves subsided, the nurse turned to the counselor, who was all of nineteen years old in his first summer job taking care of anything more than his family dog, and said something like, Just how many hot dogs did you let him eat?

The idea of managing a child’s GI distress or allergic reactions should not be that daunting, I am certain you are saying. Didn’t you go to medical school? But one thing that a pediatric neurosurgeon likes is to be able to control those things that she or he can, because so much of what we do is far from controllable. When doctors gravitate toward superspecialized care, there is a great deal of knowledge that we leave behind, and that unknown can often seem larger than it is. I remember being grateful to our pediatrician when we brought in our son, then an infant, with a fine rash that I was sure represented platelet failure and leukemia. As the pediatrician calmed us by confirming it was simply a post-viral phenomenon and his platelets were indeed normal, he told me, “Try to just be the parent. Leave the neurosurgeon at work if you can.”

I mentioned some of this to the nurse as she gave me the crash-course tour of the infirmary soon after we arrived. She smiled, just as experienced nurses tend to, and reassured me that I would be fine. “So here is the medicine cabinet,” she continued. “Mostly allergy and over-the-counter pain medicine. Make sure you dose it correctly.” Right, dosing by weight. I got that, I thought.

“Here are the things for an upset stomach…maybe some probiotic gummies and powder for kids who are constipated. Kids do love the gummies!” Still okay so far. Ibuprofen and gummies I can do.

“And here are the buckets if you need them for vomiting.” She walked into the next room and clicked on the lights. I was briefly confused: Wait, why would I be vomiting? “In these two rooms are all the beds if there are a bunch of kids vomiting at once…I remember last summer…” and her voice trailed off as she gazed into a memory that did not seem pleasant. Two roomfuls of kids vomiting? This is karma coming around. I visualized a ward of kids vomiting hot dogs into plastic bins.

“Over here are the asthma nebulizers if you have someone wheezing and their inhaler isn’t cutting it.” As an asthmatic myself, I remember nebulizer treatments from years ago and how much they worked when I needed them to. I had her go over exactly how to load one up with medicine and connect the tubing.

“There is a glucose monitor…”

“Oh good grief, insulin,” I blurted out. “Will I have to dose insulin? I haven’t done that in…ever. Is there some kind of guide?” I was starting to sweat now.

“No,” she answered and laughed, looking slightly sideways at me. “We keep this tube of icing here in case someone has low blood sugar. High blood sugar doesn’t really present as lethargy. Plus, most kids either have these fancy new insulin pumps or know how to run their own insulin now.” I was thinking about how I had a 950-page textbook in my backpack that one of my ER friends had loaned me and that I needed to read about hypoglycemia as soon as the nurse was done with me.

Lastly, here was the drawer of EpiPens. That’s enough epinephrine to revive the dead, I thought.

When it was clear that the tour was over, I found myself telling stories to the kind nurse as a way to both calm myself and somehow keep her there. Finally, she said it was time for her to leave and that I would be fine. The last thing she did was give me her number and then show me the Wall.

The Wall was not immediately noticeable when I walked in, but it was clearly visible from the desk. On the side of one of the tall cabinets, the names and telephone numbers of nearly all the camp doctors and nurses over the years were written on strips of masking tape—all lifelines available to call in case something presented itself that was unfamiliar. I looked up to see the names of longtime friends, anesthesiologists, obstetricians and gynecologists, neonatologists, adult cardiologists, and even one of my old neurosurgery residents from the University of Alabama at Birmingham who had sons here (and whose wife is a pediatrician). There were contacts for orthopedic surgeons down in the nearby town, notes on how to call in local prescriptions, and emergency treatment pathways. All of it there, left for the next person sitting at that desk to know that others had been there and that the collective wisdom and care permeated these very walls and floorboards.

Soon enough, I had removed a tick, helped the director of the kitchen manage her reaction to her blood pressure medicine (finally sending her to the ER), and iced and wrapped a camper’s strained wrist. Quickly I began to realize that much of what I would see would be what I learned years ago as a Boy Scout. As the day wore on, the counselors would call up by radio to send me the walking (barely) wounded. I cleaned and bandaged a few scrapes and taught the boys how to do it as I went, perhaps a little too neurosurgical in my approach at times: Okay, Charlie, tell me the three steps of dressing a wound again. Eyes front. Don’t you look at your dad.

I iced and wrapped a few sprains from overexuberant adults, handed out ibuprofen like candy, and treated one counselor’s new onset seasonal allergies, going so far as to recommend a long-term treatment plan and specialty care in their home city. For the nighttime activities, I went mobile by taking up a first aid kit and a camping headlight and walked around to see if I was needed anywhere.

At one point the next morning, I heard over the radio a crackled and garbled message: …archery…first aid…emergency… and nearly leaped into action while going over the management of puncture wounds in my head. I had just picked up the radio and was about to yell into it, “Whatever you do, do not pull the arrow out,” until the message repeated itself more clearly: This is archery. We need a first aid kit to get some tape. It is not an emergency.

By the end, there were none of the pediatric emergencies that I had concocted, no broken bones or torn ligaments. All the known blood glucoses must have been normal, and no asthmatic flared (myself included). The vomitorium ward was quiet.

I know that two decades of pediatric neurosurgery call has prepared me for the worst of the worst, and society needs specialists ready to act when the time comes. But this work is so important too. In a way, camp doctoring was the very type of medicine that I thought I would be entering years ago when I first went to medical school. Helping people, connecting with them, and then showing them how to help themselves. Despite hospital mergers, electronic medical records, forms in triplicate, pandemics, vaccine controversies, and being surrounded at times by the suffering who I am not able to aid, it was important for me to connect back to why I chose this path. Whether I was dissecting a tumor off the brain stem five hours into a brain surgery or cleaning and bandaging a seven-year-old’s scraped finger, the compassion and the connection sustain us and move us all forward.

At the final lunch before traveling home, two of my adult patients stopped by, one to thank me for successfully extracting his tick and noting that both patients survived, he and the tick (I’m not much of a bug killer). The other thanked me for treating his allergic symptoms and noted how much better he felt and that he would follow up as I suggested. Then children with their dads close behind walked up for a handshake and a thank-you before their own journey home.

As I packed up my clothes (and one completely unused 950-page textbook) from the small bedroom just off the infirmary office, I looked up at the Wall. With just a bit of ceremony, I put up my own strip of masking tape in the space just between two others, yellowing with age, and wrote my name and number there. Then with one last look, I clicked off the fluorescent lights, closed the screen door, and headed home.

Jay Wellons is the author of the recently released book All That Moves Us: A Pediatric Neurosurgeon, His Young Patients, and Their Stories of Grace and Resilience.

Garden & Gun has an affiliate partnership with Bookshop.org and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a book. All books are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.