I first fell in love with Texas while swimming in the Guadalupe River after dark. Just downstream rose the silhouette of a two-lane bridge—FM1340, leading ten miles east to the town of Hunt and empty of drivers at this late hour. Limestone bluffs hugged the opposite bank, and the Perseid meteor shower threaded the sky with silver.

In a few short weeks I’d begin my new teaching job at a small Austin private school. To kick off the year, my colleagues and I had gathered for an all-staff orientation at Presbyterian Mo-Ranch Assembly, a five-hundred-acre retreat center and summer camp nestled along the Guadalupe two hours west of Austin.

I was new to the state, and in the year since I’d arrived its shrubby trees and ubiquitous limestone had yet to grow on me. The oaks and maples I knew back east in Virginia formed lush canopies high overhead; the mountains were rich with blue-gray shale and rivers the color of tea. This sun-beaten new landscape felt disorienting.

At the Guadalupe that night I was joined by a fellow teacher who shared my penchant for spontaneous night swims (and would, in the tradition of all great summer camps, become one of my closest longtime friends). As we slipped into the cold water, its surface reflecting the stars overhead, our hushed conversation fell into total awestruck silence.

A hundred million years ago, the shallow Cretaceous Seaway flowed across Texas, essentially dividing what is now called North America in two; its marine deposits form the hills and caves that define much of Central Texas today. Along the Balcones Fault, cool water streams from porous limestone, creating treasured swimming holes like Jacob’s Well and Blue Hole in Wimberley, and Austin’s own Deep Eddy and Barton Springs. Numerous rivers and creeks run toward the Gulf, nourishing local wildlife and providing community gathering places for human inhabitants.

Kerr County, situated on the Edwards Plateau in the heart of Hill Country, is home to both the Guadalupe and its two tributaries, the North and South Forks. Summer camps, many of which date back a century or more, line their banks. The county is also at the center of Flash Flood Alley, a swath of land that cuts diagonally across the state from its southwestern border. In the dark, early morning hours of July 4, slow-moving thunderstorms collided with an unusual degree of tropical moisture in the air to spawn the river’s second-highest flood on record, as the current surged from around a gentle 400 cubic feet per second to a stunning 120,000 cubic feet per second. At least 120 people lost their lives in the torrent, and as of this writing, at least 173 are still missing.

Mo-Ranch—where I once swam under the stars—evacuated its campers early, but the nearby Camp La Junta and Camp Mystic were caught off guard by the swiftly rising water and an ineffectual emergency alert system. The boys at one La Junta cabin survived by clinging to the rafters, flashes of lightning briefly illuminating the darkness. When the water eventually began to recede, counselors carried them to safety. At the all-girls Camp Mystic, the flood swept away and killed at least twenty-seven campers and counselors.

Among the victims was the camp’s owner and director of over fifty years, Dick Eastland, who died trying to rescue campers. Texans of all ages harbor warm memories of him. Hanly Banks, who grew up in Houston and spent her childhood summers at Camp Mystic, spoke with me by phone from her home in Austin. “You’ll never meet people this nice,” she said of Eastland. As a role model, he provided her with “an embarrassment of riches.”

After that night under the Perseids, I remained in Austin for over a decade. In the autumn of my first year teaching, the whole school—including roughly two hundred students—traveled back to Mo-Ranch for three days of riverside games, swimming, and talent shows where previously reserved teenagers told stories and performed songs. I spent summers swimming in Barton Springs and Deep Eddy or ducking into community pools after hours for a clandestine (if not particularly legal) night swim. I most loved, however, the emerald or jade-colored creeks and rivers. Floating along on my back, staring up at the enormous cypresses, I felt as though I’d slipped into some other primordial time and place.

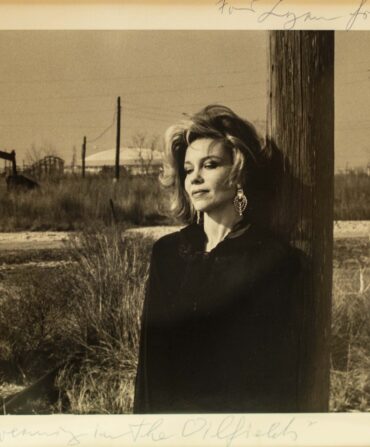

I wasn’t alone. “The rivers always felt more special,” said Dottie Wagner, a former Texas resident who grew up in San Antonio, in a phone interview this week. “Something about the water flowing over you and having it surround you.” As a high school student, Wagner enjoyed countless weekends at the nearby Guadalupe, “dam sliding” or just sitting on the limestone ledges and grooves in the shallows. “It’s a Texas thing. You go to the river.”

Although my conversation with Wagner was full of nostalgia, the still-unfolding tragedy on the Guadalupe overshadowed each memory. Other exchanges with friends included safety check-ins, anecdotes of escape, and news of those who lost someone. One close friend, whose children planned to attend both Mystic and La Junta later this summer, texted: “We can barely form a sentence yet.”

Banks had been excited for her ten-year-old son to attend Camp La Junta for the first time last week, with its natural beauty, comradery, and outdoor recreation providing a respite from screen time. While her son was among those safely evacuated from the flooded cabin, I could hear her voice constrict as she recounted his harrowing experience.

We pivoted to her own summer camp memories and her voice opened, making room for grief and joy. She described the omnipresence of music—whether songs, chants, or the Bangles’ 1980s hit “Manic Monday” blasting over the camp loudspeaker each morning. “Mystic was the place that you went and it just made your life better.”

Austin resident Ladye Anne Wofford, who attended Mystic for six weeks each summer from age nine through fifteen, echoed Banks’s feelings. She shared that many Texans had such a “life-changing, beautiful experience” at both Mystic and La Junta that they now send their children. Her own nine-year-old daughter attended Camp Mystic the past two years and was scheduled to go back later this summer.

For Wofford, too, music played an important role in her time there. “[We sang] lots of beautiful, fun camp songs, songs that we would sing in rounds…a lot of songs that are just funny.”

The camp is nondenominational, but Wofford told me that evening devotional songs along the water at night were a part of its magic. “We would light candles and sing and look out over the mist,” she said, choking up. “Just singing in the glow of candlelight, right there on the river.”

I asked if she recalled any songs in particular. She sang me her favorite:

There’s a camp on the Guadalupe River

It’s the camp of my dreams

Where the whip-poor-wills blow softly

And the bright moon beams

On the banks of the Guadalupe River.