Even at eighty-five, I have never acquired much wisdom, other than perhaps the value of reticence and avoidance of judging others, lest I invite condemnation of myself. That said, I did learn a lesson many years ago about the earth and humankind’s duration on it and the great ironies that often characterize our lives.

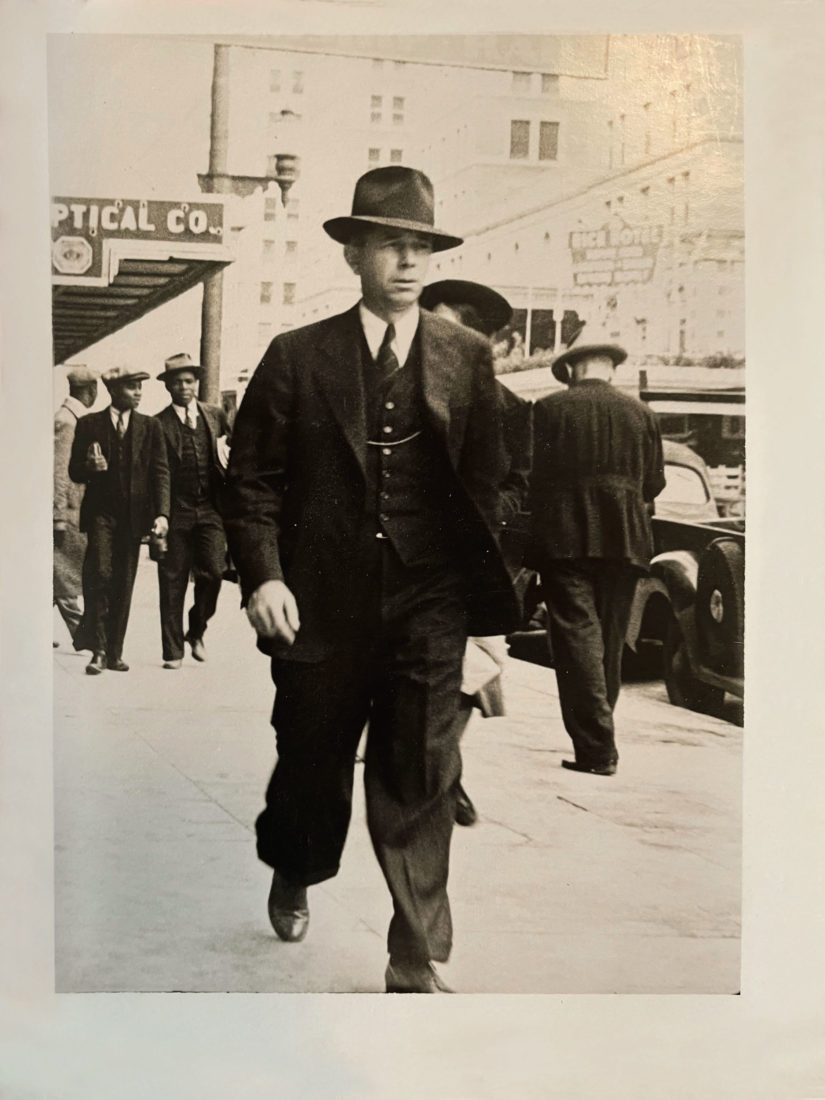

My grandfather was Walter James Burke, one of Franklin Roosevelt’s appointees to the Public Works Administration, and one of the few men in Louisiana who had the courage to testify against Huey Long during Long’s impeachment hearing. He was also one of the most admired attorneys in the history of the state, particularly for his charity and integrity. In January of 1941, when I was a very little boy, my father and I rode the train from Houston to New Iberia to be at my grandfather’s bedside in his last days. The train was crowded with soldiers, the cars musky, the window glass cold. My father stood all the way, even though several soldiers offered him a seat; I sat on his suitcase. The sky was gray, the stubble in the cane fields smoking, the ash black, spinning into the sky. My grandfather died the next morning. His last words were “The final chapter is written. The book is closed. God forgive me for not teaching my children religion.”

The next day was unseasonably warm, the sun spangled in the live oaks along Bayou Teche. Then a purple cloud moved across the sun, and immediately rain rings chained the surface of the water. Even at my early age, the rain always struck me like a secular baptism—cold and clean and magical, clicking on the live oaks and palm fronds and the elephant ears that undulated in the current humming like a sewing machine close to the bank. Back then southern Louisiana was Edenic, like an island that had floated loose from the Caribbean and attached itself to the rim of the American South. I loved Louisiana, as I do today, but I did not know that Louisiana is like the drunken courtesan who drowns in her own laughter while the vilest of the vile rob her of all her gifts.

After the funeral, it was obvious my father was concerned for me, and he put his hand in mine and walked with me along the Teche and began to tell me stories about the events in and around New Iberia in the spring of 1863, when General Nathaniel Banks and twenty thousand Union soldiers invaded southwestern Louisiana. Among the cypresses and willows and oak trees along the bank, the bow of a Confederate gunboat jutted like a giant brown rotted tooth from the mudflat. My father pulled a rusted iron spike from one of the timbers and handed it to me. It was heavy and crusty in my palm and left a wet orange smudge on my skin. Up the slope was a plantation home that had been burned to the ground, the Roman columns standing starkly in the rubble.

“Why are we here, Daddy?” I asked.

“I know you’re sad about your grandfather. But you shouldn’t be.”

“Why shouldn’t I be? Papa was my grandfather.”

“He lived a good life and tried to make the world a better place. This plantation represents the world in which he grew up. That monument has been destroyed. But your grandfather’s deeds have not.”

I understood nothing of what my father said.

“I tell you what,” he added. “You’ve never gone fishing, have you?”

“No, sir.”

He winked. “Let’s take care of that.”

We walked back to my grandfather’s home, a rambling two-story brick house with a gazebo built on East Main in 1927, and borrowed two bamboo poles from a Black man named Batist. Batist owned a cat named Tom who used to sit with his tail in a pool of water on the brick patio at the back of the house. No one knew what Batist did, nor did anyone ever ask. He came in the morning with his cat, smoked his pipe for several hours in the shade, then took his cat back home. The pole he gave me was strung with green line, a hook, a carved piece of wood for a float, and a perforated .58-caliber minié ball that he had found by the crumbled plantation house down the bayou. He also gave me a tin can of night crawlers. Then my father and I walked along the water to an enormous live oak and swung our lines into a quiet pool on the edge of the current.

Right next to us sat a deserted cabin that had once been the quarters of an enslaved family. Now it was stacked to the roof with baled hay. Like the cabin, the ancient oak under which we stood was another reminder of Eden gone wrong, this one even darker. Long ago three chains had been nailed with iron spikes to the oak’s trunk, and slowly the tree began to subsume the chains, as though to conceal their purpose, burying them in the heart of the wood, a few stiffened loops protruding from the bark, like snakes with broken backs. I asked my father why the chains were there.

“This is where Jean Lafitte and James Bowie moored their boats and held slave auctions,” he replied.

“James Bowie was friends with a pirate?”

“Bowie was a brave and good man in many ways, but in some ways he was not. We have to accept people as they are, Jimmie.”

I knew better than to continue. My father did not like to talk about evil. He lost his best friend in France on the morning of November 11, 1918, and he would walk out of a room when people talked in a celebratory fashion about war or militarism.

Suddenly my bamboo pole plunged in my hands, the carved floater disappearing in the murk, the fishing line beading with drops of water. I jerked the pole with all the power I had in my little arms and ripped a goggle-eyed perch from the bayou’s surface into the tree limbs overhead. The cane pole was snapped in half and hanging with the fish and the floater and the minié ball and the fishing line in the leaves and twigs and Spanish moss on a thick limb. The goggle-eye was dark green and brassy, its gills swelling and closing as it tried to breathe. I felt sorry for the fish and wished I had not caught it.

My father stared up at the limb. “I think we have a dilemma here.”

“What’s a dilemma?” I asked.

“Wait here. I’ll be right back.”

He walked up the incline, then returned with a ladder and a garden rake he had borrowed from Batist and combed the broken pole and the goggle-eye out of the live oak. Then he dipped one hand in the bayou, picked up the fish, slid the hook from the corner of its mouth, and crouched down by the water and let it swim from his hand.

“I think we made history, Jimmie.”

I had no idea what he meant.

“We may be the first people in the world to catch a fish in a tree with a garden rake,” he said. “Secondly, we used a minié ball that was fired seventy-eight years ago by a Yankee soldier and missed the target and ended up as a weight on your fishing line.”

“How do you know a Yankee fired it, Daddy?”

“There are three rings on the lead. The Rebs had only two rings on their bullets. But don’t worry about that. Batist is the descendant of slaves owned by our family. Yet it was he who let us borrow his fishing poles and minié ball and worms and the rake we used to catch a fish in a tree.”

I could not keep up with what he was saying.

“It means this, Jimmie. There are only two things you have to remember about the nature of God: One, he has a sense of humor, and two, he’s a gentleman, and as such he always keeps his word. Don’t ever let anyone tell you different.”

So when the days and the seasons pass and I have a melancholy moment and wonder about the great mysteries, I think back on that day when the Axis powers had already begun their attempt to turn the Big Blue Marble into a concentration camp, and I take solace in my father’s patrician humanity and Batist’s generosity and his cat with his tail in the water and a fish that contravened its own evolution and a God that gave us Eden, if we would only recognize the bargain that is all around us.

I think it’s not a bad way to be.