Before Joe Namath was one of professional football’s most famous quarterbacks, he was a kid from Pennsylvania playing college ball under Coach Paul “Bear” Bryant at the University of Alabama. In Namath’s three years at Alabama, he led the Crimson Tide to a 29-4 record and a national championship his final year, in 1964, and Bryant once called him “the greatest athlete I ever coached.” As a pro, Namath would go on to guide the New York Jets to victory over the Baltimore Colts in one of the biggest upsets in sports history in 1969’s Super Bowl III.

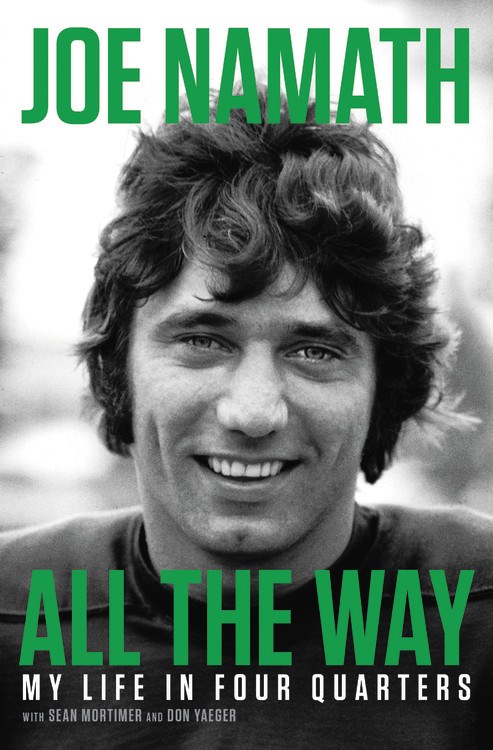

Now a resident of Tequesta, Florida, Namath, who is 76, released a rollicking autobiography this spring, All the Way: My Life in Four Quarters, which offers an intimate look at his college and pro years, struggles with alcohol (he abstains now), plus his abiding sense of fun. We chatted with the Hall of Fame quarterback about his memories of Coach Bryant and his thoughts on Southern sayings, fishing, and fried okra.

You’re calling from Florida, where you’ve had a home since the 1970s. What was your first experience of Florida?

When I was in college, Coach Bryant had given us three days off before we played in the Orange Bowl in Miami in January, so I went home and visited my family in Pennsylvania. Driving back to the airport, we had snowflakes falling the size of silver dollars. When that plane landed in Florida and I walked out on that platform, the first thing I saw—flowers! They were red and white flowers, orange flowers. The colors amazed me. I had never seen anything in the wintertime like that. Now I know those flowers were probably some bougainvillea.

Do you grow your own flowers now?

I do have bougainvillea here, too. I have plenty of yard. We planted some oak trees. I have jasmine and honeysuckle. I like the aroma, the fragrance. And I have ficus hedges that border the whole area. I love nature, and I appreciate the colors blue and green better than gray and brown.

I’m looking at a beautiful river right now. I live on the Loxahatchee River down here, and I go fishing. But I’d rather go catching. I have friends I love to go with because they know where to go, when to go, what to use, how to use it, and what’s going to be there. I’m not that astute when it comes to being successful at catching. But off my dock, I can catch redfish, snook, and snapper.

In your book, you talk quite a bit about how Coach Bryant shaped your life, including that he taught you how to negotiate?

If you could picture it, we’re in the locker room after the game with Auburn [in 1964], our last game. We won. And our quarterback that game, Steve Sloan, hurt his knee, and that’s why I played a bit. [Namath had been battling his own knee injury that season.] Well I was down on the floor on one knee putting Steve’s sock on his foot, and Coach Bryant comes walking over. He’s standing there and says, “How you doing, Steve?” Steve says, “Okay, coach!” And Steve sounded like Jiminy Cricket. High pitched country voice, kid from Cleveland, Tennessee—“I’m fine, coach!”

Coach Bryant takes a big old draw off one of his cigarettes. He used to carry two packs—Pall Malls and Chesterfields. He says, “Joe, you know the pro scouts are going to be coming around talking to you about pro ball, and do you know what kind of money you’re going to ask for?” I’m finishing up with the sock and putting Steve’s shoe on, and I said, “Well, coach, Don Trull [the quarterback for the Houston Oilers at the time] signed for $100,000 last year, and I think I’ll ask for something like that.” He took another draw off that cigarette and blew it out and said, “Well, you go ahead and ask them for $200,000. That’s a better place to start.” [Laughs.] Coach Bryant was a classic, a great man who taught us all about respect. He was a respectful man with everyone, unless it was someone who wasn’t giving the kind of effort he should give.

Photo: James Drake / Sports illustrated / Getty Images. Used with Permission of Little, Brown

Namath and Bryant on the sidelines.

How did Coach Bryant show respect to his players?

His respect to us started out in the first meeting we had. He told us about what we would remember if we stayed there and followed his plan and rules. If we were able to endure, we would remember the losses and the tough games quicker than we were going to remember the good games and the wins. We were going to have a lot more wins than losses, but those losses would stay with us for the rest of our lives. And I’m going to tell you what, that’s a fact. I still think back to the games we lost, where I messed up. I could go back to the Texas game my senior year or the Auburn game my junior year, or the Kansas City Chiefs game in pro ball that we lost.

And Coach Bryant told us, “I can’t make y’all study, but I can make you go to class.” Because if you had three cuts in any class, you were running at 5:30 in the morning with some assistant coach watching you until you fell. So we did go to class. I wish I had studied more, but being a Gemini—I still use that as an excuse—I needed some freedom.

You mention some phrases you learned in Alabama, like “A chicken ain’t nothing but a bird.” Any other memorable lines?

I’ll tell you one that Coach Bryant laid on me. I was a sophomore and getting ready to play Georgia in the first game of the season, so coach says, “Joe, you got the plan?” And I said, “Yessir! I think so!” And he said, “You what? You think so? Hell son, the hay’s in the barn!” And I’m thinking, the hay’s in the barn? Now what the heck… I learned after that you say, “Yessir! I’m ready!” There’s no “I think so” business.

And on the field when we called right or left, if we were going to be strong right, Coach said “Gee,” and if we were left, he said “Haw.” So in the huddle, you might say “Haw, eighty-six!” Well, that’s what you tell a mule! Gee! Haw! Coach Bryant got that from driving a mule. So I started talking Gee and Haw stuff.

What were some of your first tastes of Southern food?

We had a dining hall in the athletic dorm, and the first time I had what I thought was pumpkin pie, it was sweet potato pie. I was stunned. Sweet potato pie just didn’t sound good to me. Pumpkin pie we had in Pennsylvania. But on my second bite it tasted good, and on my third bite I loved sweet potato pie.

I’ll tell you what, I like okra, too, but the first time I had fried okra, I did not care for the texture. It wasn’t exactly crisp—it tried to be crisp. It was slimy for the most part. Now my diet’s changed quite a bit, and there are a lot of things I don’t add to my food such as salt and sugar. There was a time I got my sugar from alcohol. I didn’t even know alcohol had sugar in it. Last night I had two bags of vegetables with tuna fish and put some cinnamon on it and some cayenne pepper and olive oil and vinegar and that was my dinner. And I take a line from Mary Poppins now: “Enough is as good as a feast.”

Photo: Courtesy Little, Brown

Namath and two of his grandchildren on the beach.

What do you hope people take away from your book?

It’s the fiftieth anniversary of the New York Jets championship victory in 1969, the first time the AFL beat the NFL in a championship game. And there are experiences from then, and from my life, that I’ve learned I could share. It doesn’t matter who you pull for. I think that all of us who feel like we’re underdogs from time to time, and I know I do, we pull for the underdogs to come through. Part of this book is trying to stress that if you have a passion, if you have a dream, keep trying to make it come true. Don’t let anyone say that it’s too big for you. That’s one of the messages in the book that I swear by, that I live by.