Without setting out to, I’ve somehow become a cookbook collector. I read them front to back, taking in new tips and techniques, even for dishes I’ve cooked many times. I find myself flipping through them while I watch television, missing major plot points in favor of insights on a new marinade or superior seasoning technique. Recently, though, rather than opening something new, I carefully pulled from the shelf a black notebook falling apart at the seams that had belonged to my paternal grandmother Ruth Sikes Orr, better known to the residents of Monroe, North Carolina, as “Toodie,” a nickname she’d had since childhood.

Toodie, who died in 1999, was known for many things, but cooking wasn’t necessarily high on the list. Not because she wasn’t a wonderful cook—she made dinner for her family of six every night, and her Thanksgiving dressing is the stuff of legend—but she was more likely to be remembered as the person you wanted beside you at the table, someone with a sharp sense of humor who left everyone feeling in on the joke. There was hardly a kooky story or embarrassing anecdote that couldn’t be laughed off. “They’re ours, and we love them,” she’d reply, a simple phrase that meant we accepted our people for who they were—and we seemed to have a lot of people.

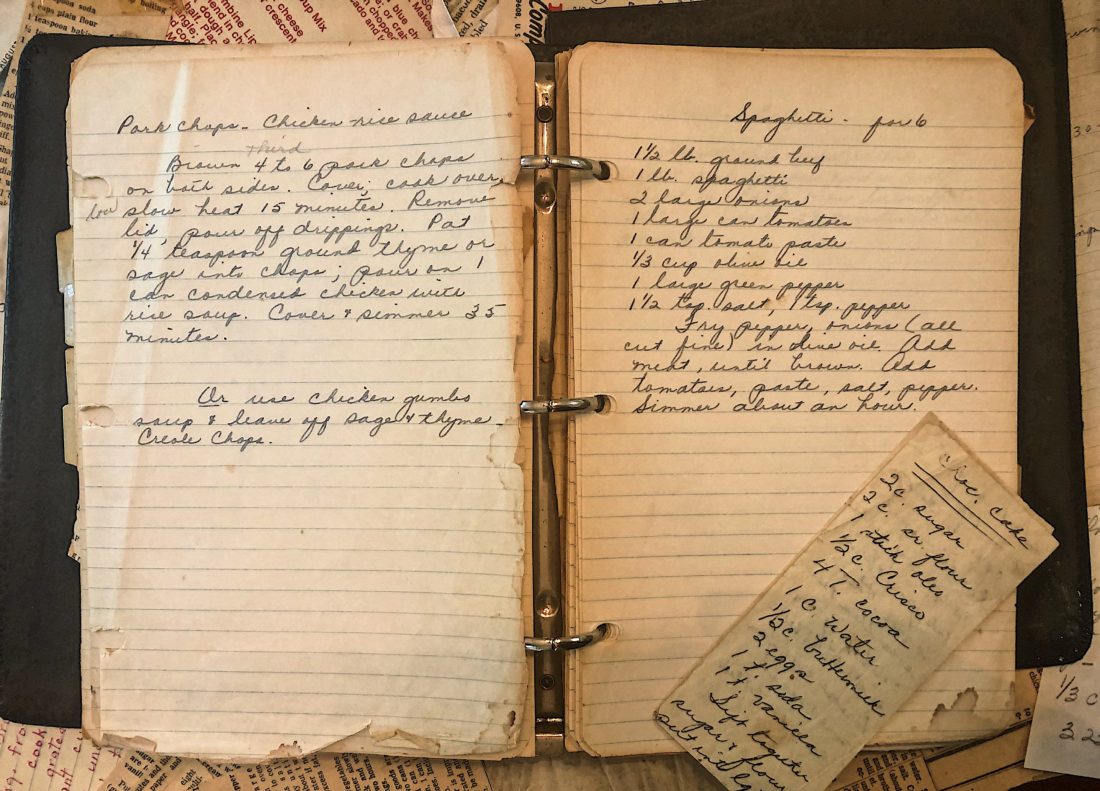

Cooking was primarily a tool to bring her family together, at least for a few moments around the table each day. For many years, Toodie kept the same menu every week: pork chops with field peas and spinach on Tuesdays; spaghetti on Fridays; Campbell’s soup with fruit on Sunday nights. The menus became so deeply ingrained that years later in Atlanta, when my mom invited my dad’s sister Ruthie over for a casual weeknight dinner, she declined immediately upon hearing that meatloaf was on the menu. Ruthie told my mother it was because she didn’t like little green peas. “Your mom was like, ‘What? I’m not making peas,’” my dad recalls with a laugh. “I had to explain to her that for us, that whole meal went together.”

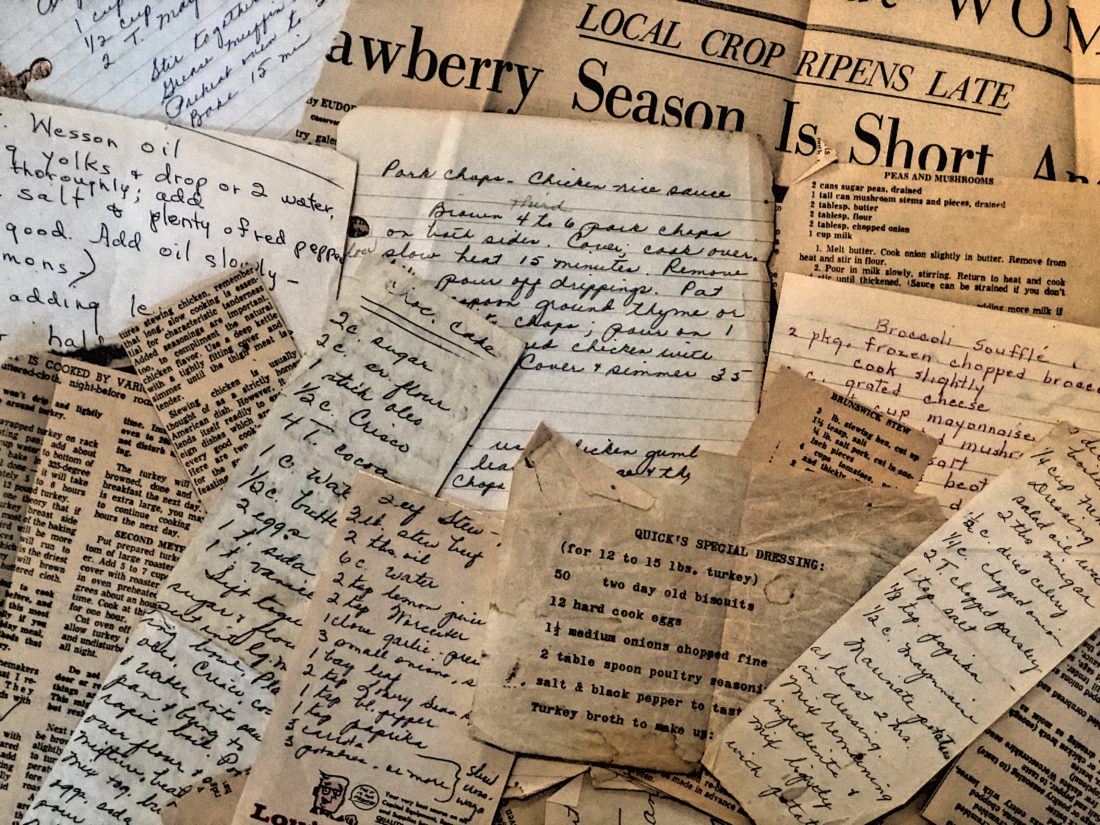

Several years ago, when I was first trying my hand at home cooking, Ruthie brought the worn-out notebook that served as Toodie’s cookbook to our family Thanksgiving gathering at my parents’ house, pressing it into my hands before she left that night. Later, I finally gave the book a proper look, and it didn’t take long for me to fall fully down the rabbit hole. There, handwritten in Toodie’s perfect cursive, lie the secrets behind many of those regular menus I’d heard about for so many years. The weekly pork chops are to be seasoned simply, browned, and topped with one of two condensed soups—chicken and rice or chicken gumbo—or tomato sauce. Spaghetti has three entries, seemingly differentiated by how much time you have before dinner needs to be ready. There are more dated entries—tomato aspic, tomato crab meat aspic, Mrs. Jonas’s tomato aspic, you get the gist—but enduring classics such as cheese straws, biscuits, and coffee cake fill the pages, too. She also clipped recipes: cereal boxes snipped and saved with dishes we still make today (albeit by Googling them), such as Toll House cookies and Rice Krispies Treats; a frozen orange treat from 1955, predating my dad; a four-ingredient recipe for Icebox Candy, the “honorable mention” in a newspaper recipe contest (the winner nowhere to be found). There are recipes from friends, too, easy to pick out not only for the different handwriting, but by the notes left at the bottom: “I loved seeing all of you,” writes a friend, below what looks like a decadent Grits-Cheese Casserole recipe, “but missed seeing Ruthie and Bubba. Anybody come to spend the night with us anytime.”

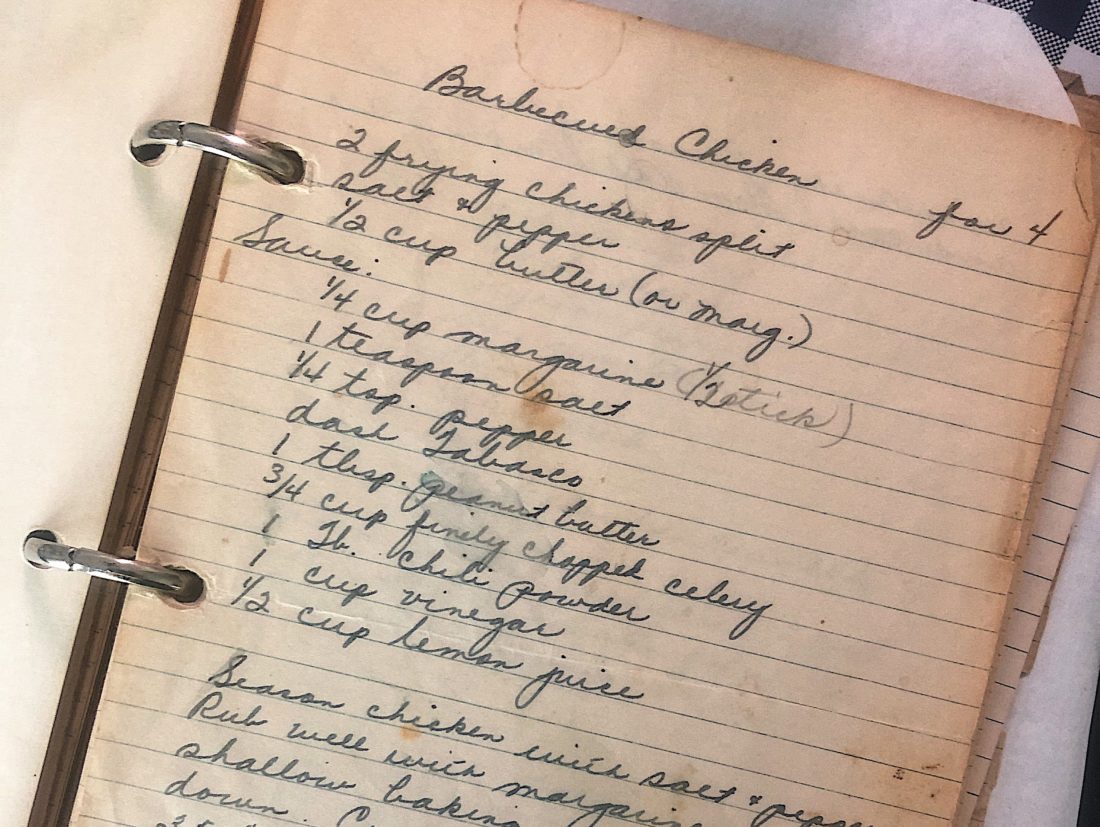

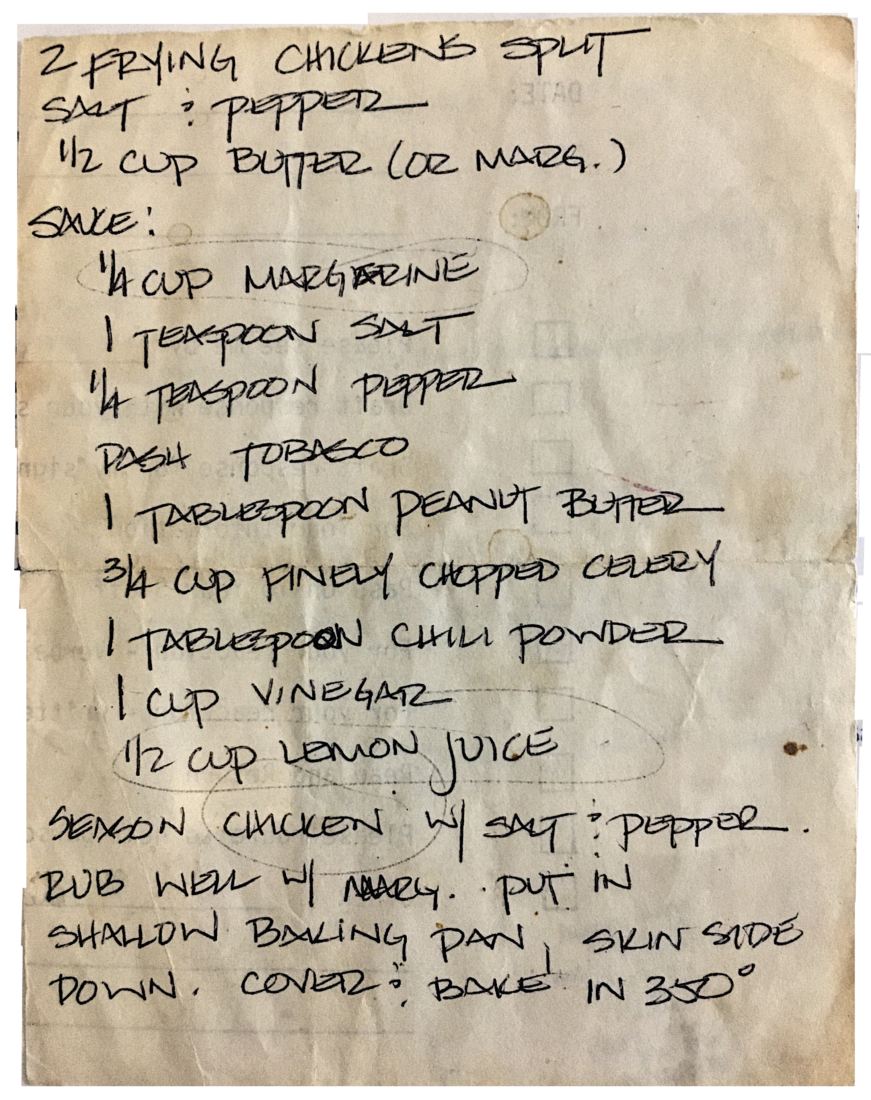

Like any good cookbook, you can spot the most popular entries by how many drips and stains adorn the page. Her barbecue chicken certainly counts among them: The recipe calls for peanut butter, an ingredient that surprised me and my father, despite the fact that he vividly remembers the dish as an after-church staple. “You mention that recipe and I’m right back there in the dining room,” he says. “I can see the little bits of celery, the Sunday clothes, down to the damn wallpaper.” His other sister, my Aunt Liz (Elizabeth, always, to Toodie), was less phased by the ingredient list—she’s been cooking it regularly ever since she went home to Toodie’s one weekend years ago and copied down those handwritten recipes in her own all-caps scrawl.

Whether cobbled together in a falling-apart notebook, scribbled on scraps of paper in my family members’ kitchens, or intertwined with their memories of Sunday suppers and school nights, these recipes feel like a stolen glimpse into the life of a woman I wish I’d had more time to get to know. And at a time when many of the splashier events in life feel like they’re being postponed or taken away, the routine these recipes represent serve as a reminder that some of the best memories are made in the mundane moments—the little green peas, Sunday night soup, the cardboard cutouts. Fancy or not, they’re ours, and we love them.

Dacey Orr Sivewright is a writer and editor based in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina. An Atlanta native, she was Garden & Gun’s digital editor from 2016 to 2021 and has spent the last decade and a half covering music, food, and culture for Billboard, The Village Voice, Stereogum, Apartment Therapy, and other outlets. When not writing, she’s probably making a mess in her kitchen or spending time outside with her husband and daughter.