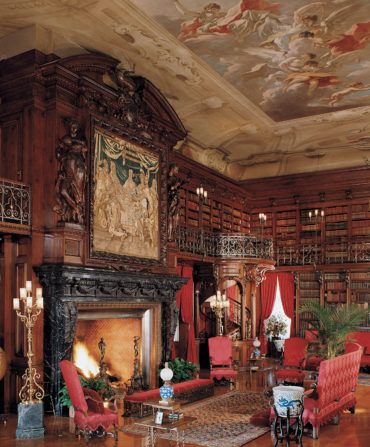

George has always been the Vanderbilt who Southerners know best, a credit to his opulent Biltmore Estate in Asheville. But thanks to the Raleigh, North Carolina, writer Therese Anne Fowler and her page-turning new work of historical fiction, A Well-Behaved Woman, another member of the Gilded Age family with roots in the South may soon get her due.

Born in Mobile, Alabama, in 1853, Alva Smith agreed to marry William K. Vanderbilt, one of George’s older brothers, during a party at the storied Greenbrier in West Virginia in 1874. William, a grandson of railroad tycoon Cornelius “the Commodore” Vanderbilt, was an eligible young bachelor, but Alva had something even he couldn’t attain: a family name respected by society—her parents’ families had been in the South a century before the Revolutionary War, and she could trace her lineage to both French and Scottish royalty.

The Vanderbilts, on the other hand, were still considered nouveau riche, and New York’s upper crust shunned them. William and his eventual inheritance—about $1.5 billion in today’s dollars, after his father died—would offer Alva something she needed, too: security. Though her parents had decamped for New York before the Civil War, the family was nearly destitute. As Alva later quipped: “First marry for money, then marry for love.”

And so she did. Once she was a Vanderbilt, Alva revelled in what her new fortune could afford her—jewels galore, including a rope of pearls that once belonged to Catherine the Great; the largest luxury yacht in the world; a stunning Manhattan mansion on Fifth Avenue; furniture originally made for Marie Antoinette; summer homes on Long Island and in Newport, Rhode Island; and the ability to support numerous charities, many focused on poverty.

She also used her wealth to find ways to work around New York’s insular Knickerbockers. When they wouldn’t sell the Vanderbilts a box at the Academy of Music, she helped found the Metropolitan Opera. And when the grande dame of society, Caroline Astor, wouldn’t receive her, Alva threw a party in 1883 that put the “gilded” into “Gilded Age”—a costume ball for 1,200 people that cost a staggering $3 million—and left the Astors off the guest list. Caroline capitulated and invited Alva to her home, unable to resist the allure of the gala of the century—and with her approval, the Vanderbilts evolved into the dynasty we know today.

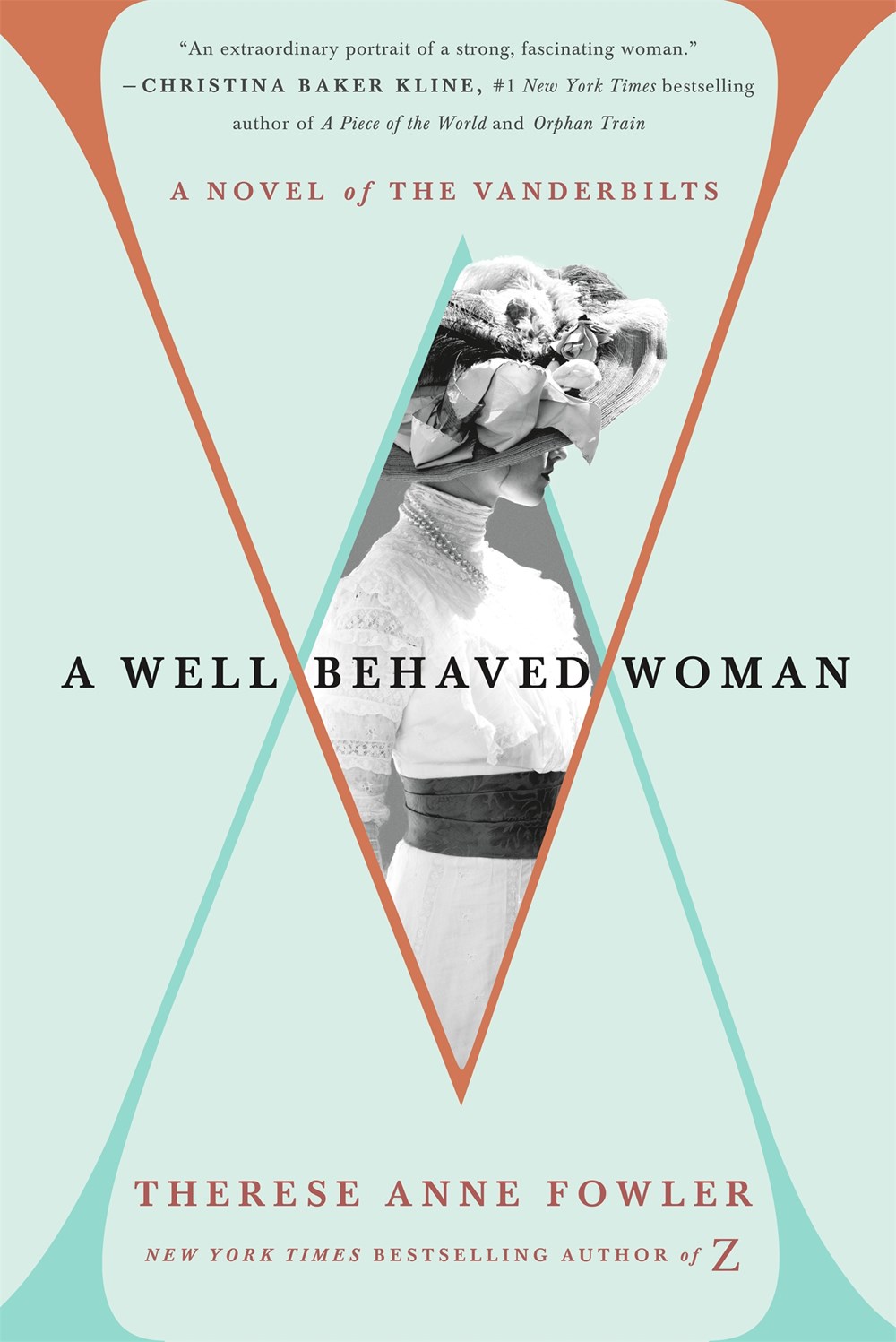

Photo: Alamy

Alva Vanderbilt Belmont

Alva defied convention at every turn: She built grand houses, working hand in hand with the esteemed architect Richard Morris Hunt to shape their designs. And she divorced William after he proved unfaithful—practically unheard of at the time. When she remarried, she did so, yes, for love, to Oliver Belmont, heir to August Belmont, for whom the Belmont Stakes is named. And she spent her latter years campaigning wholeheartedly for women’s suffrage, founding the National Woman’s Party and bucking the status quo by including the rights of black women, who were often neglected by the movement.

On Equal Pay Day in 2016, Alva’s contributions were acknowledged when President Barack Obama christened the Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument in Washington, D.C. In general, though, Alva’s accomplishments have remained unsung—Fowler’s riveting novel, and a subsequent in-development series with Sony Pictures Television, may just change that. Here Fowler—who also wrote Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald—reveals how she fashioned this three-dimensional portrait of an overlooked but zealous Vanderbilt.

How did you discover Alva’s story?

I found this article that was about Gloria Vanderbilt, who we know as a fashion designer and artist and the mother of Anderson Cooper, and it was about how in 1934, her aunt [Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney] sued her mother for custody. And I gathered that women who are a generation or so older than I am are fairly familiar with that story, about little Gloria and how her family was basically tearing itself apart over who should have custody of her, and I was really interested in that—like, who are these people?

Each step back led me further into the past. Of course, the women are the ones who history doesn’t pay attention to, or doesn’t treat very kindly. I started reading the things that people think they know about Alva [Gloria’s great-aunt], and eventually what I came to understand is that she’s been maligned in so many of the same ways that Zelda Fitzgerald was maligned, and been reduced to this caricature. When I see that happening it gets me excited about finding out what the real story is, about who these people are.

Because you didn’t initially like Alva as history had recorded her, right? She was known, you’ve said, as pushy, selfish, materialistic.

Exactly. And that was my initial response to Zelda, too. I should have learned my lesson!

When did your opinion begin to change?

It was really late in the writing process when I sort of got clear on how she must have been, who she must have been. Even early on, when I was taking on the project, I was still sort of fascinated by this woman who was so different from all of the other women of her time and her class.

How do you think Alva’s Southern upbringing influenced her?

I’m sure it had a fairly strong effect. She was about six years old when her family left the South and moved to New York City, so she was quite young, but of course she had her family around her. And some of the slaves who had been emancipated were working for them in the household as paid employees. Something that no one in Alva’s biographies addressed in any substantive way is the fact that Alva was one of the only women’s suffrage supporters who not only wanted to include African American women in the suffrage effort, but actively took great pains to make sure they were included. It wasn’t just lip service. So in order to understand how this person could have come to be this way, I of course had to look at who was around her while she was growing up, and why would she have these attitudes?

Even so, within the women’s suffrage movement, Alva’s name doesn’t come up as often.

I think that what happened to her is what often happens with women who are a little bit abrasive to other women: They get judged. Alva didn’t fit with the other women suffragists, the ones whose names that we recognize, because she came from this place of great privilege in comparison to them, and because she wasn’t the one actively getting her hands dirty, the way some of them were, and also because she had this attitude that was much more aggressive than a lot of the women were comfortable with at the time. She had to go and form her own organization, essentially, because she was getting impatient with the attitudes of some of these other women.

With a work of historical fiction, you have to couch what you can’t know—conversations, inner thoughts, private moments—in what can be known. How did you go about your research?

I’ve got everything from biographies that are specific to Alva to others that are more broad about various members of the family, and newspaper articles. I read a lot of literature set in the era—Edith Wharton, Henry James—and historical cultural books like Fashions of the Gilded Age. There’s this big fat, fantastic book that’s called New York in the 1880s. I had to learn about the architects, I had to see the city at that time, and understand the politics of everything that was going on, and then try to put these real people in these real settings. It’s a terrific intellectual exercise.

How hard was it to get Alva right?

We have to be empathetic in order to represent characters, whether they’re people we invented or people who really lived. There’s an additional layer of challenge when the person is a real figure from history because there are truths known about them. So if you’re a responsible author, you can’t take liberties with the established facts. But there’s still plenty of room for interpretation. My job as a novelist is to read all the sources, and form up this view of this individual, and then try to draw from the things I know to be true about being a human being in a culture that I’ve grown up in, and try to extrapolate from there. It’s kind of an organic thing. It’s not simple.

And now A Well-Behaved Woman is in development as a possible TV series. Can you share any plans?

We have a writer signed on to the project, so it is actively in development, meaning Sony didn’t just option it and is sitting on it, which is sometimes the case. We are developing the pitch to take to networks and are hopeful that somebody will give us the chance to put it on the screen. The way that Sony has been talking about the show-to-be is that it would be an American version of The Crown with a little bit of Downton Abbey flavor. Wouldn’t that be cool to see?