Joseph Norman’s work graces the collections of such institutions as the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. His pieces have been acquired by the Smithsonian—oh, and also by Oprah. But these days, Norman is giving art students the opportunity to create work that can be seen well beyond the walls of a museum.

A professor of painting and drawing at the University of Georgia’s Lamar Dodd School of Art, Norman directs Color the World Bright, a program to create and restore public murals. And while his decades of experience in the highest echelons of the art world have made him no stranger to the questions and criticisms that can accompany art, it’s an especially important lesson in the case of murals.

“When you’re painting a wall, everyone who lays eyes on it has an opinion,” he says. “A mural becomes a matter of civic pride, with everyone dropping by.”

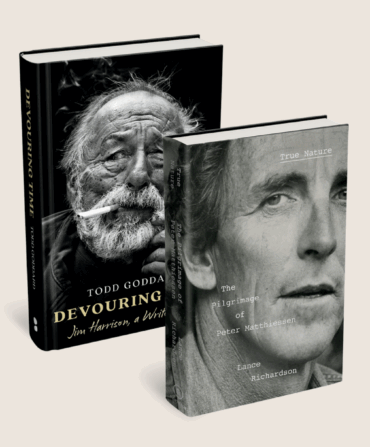

Photo: Courtesy of Lamar Dodd School of Art

Another painting restored by UGA students in Madison, Georgia.

Consider the case of a mural in Rutledge, Georgia. Never Forgotten, commissioned by the Rutledge Garden Club and completed in 2017, honors veterans. Norman and the students strove to depict a diverse collection of servicemen and women. Some sponsors of the project wanted to include a Confederate veteran, a position opposed by the students. The solution: a soldier in silhouette, allowing passersby to project their own take.

“We have a simple philosophy, to do good and bring people together,” Norman says. “Murals can transform a community.”

Photo: Courtesy of Lamar Dodd School of Art

Art professor Joseph Norman (center) with students in front of a mural they created to honor veterans.

Norman, also a distinguished visiting professor at Johnson & Wales University in Rhode Island, first devised mural projects for his fine art students as a service element of study-abroad trips that he and other professors led in the Caribbean and Central America. The Color the World Bright program brings that work closer to home, with teams of students collaborating on commissions and community projects that have ranged from an enormous portrait of Uga, Georgia’s famed bulldog mascot, on the side of a Waffle House to a 60-foot interpretation of a historic landscape in the tiny town of Tignall, Georgia, and religious panels for Ebenezer Baptist Church, West, in Athens.

In addition to original murals, Norman and his students have also branched into restoring vintage “ghost signs” on the sides of Southern buildings. In Greensboro, Georgia, they painstakingly revived a faded Chero-Cola advertisement painted on the brick façade of what is now Oconee Brewing Company (once the home of a bottling plant for the old Georgia soft drink). They restored a second Chero-Cola painting in Madison, and in Elberton, Georgia, they brought vibrant life back to a Coca-Cola sign.

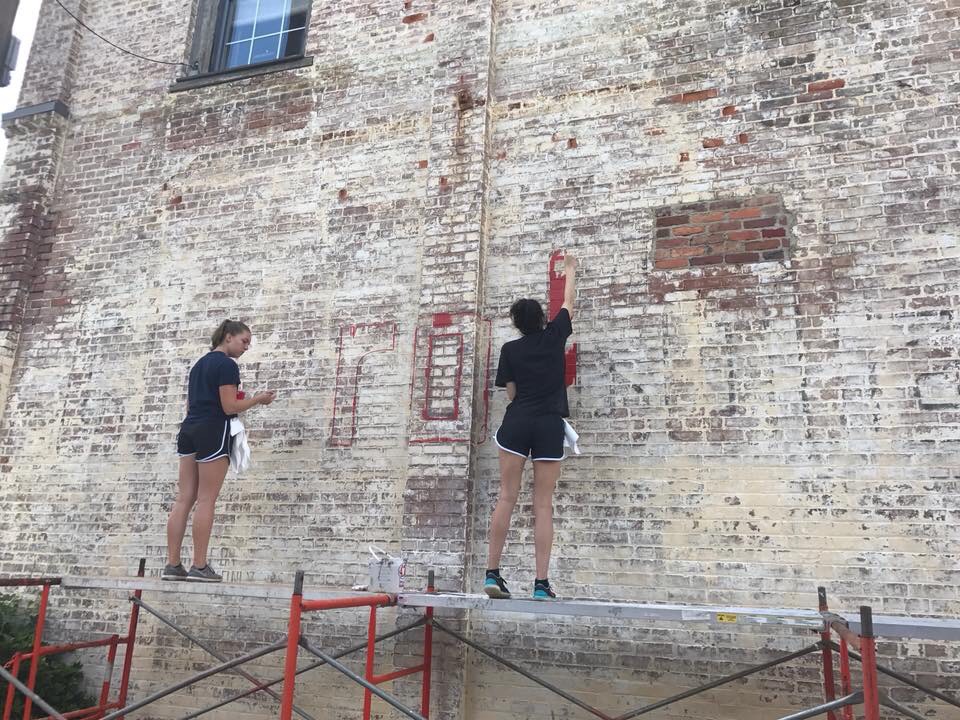

Clubs, businesses, and communities raise funds to cover the labor, and fees for the murals are paid to students as scholarship funds, with student managers overseeing the projects. “It takes a certain kind of creativity for an original mural,” Norman says, while restorations require “a very steady hand and being able to trace those curves.” Working on a mural can earn an art student somewhere between $200 and $1,000—along with bragging rights, valuable experience, and plenty of home cooking.

Photo: Courtesy of Lamar Dodd School of Art

Students begin work in Madison.

“The communities embrace the students,” Norman says. In Tignall, they were served fried catfish. In Madison, meeting a deadline to complete a mural meant missing a big Georgia game, and community members brought radios and food to the worksite.

“A mural unites a community,” Norman says. “It becomes a landmark.” He recalls, as a child in Chicago, passing the Wall of Respect, a groundbreaking celebration of black achievement and culture. “I was influenced greatly by that.” Now, he says, “I’ve come full circle.”