Tracing through tall straight trees, the old logging road shows no brighter than a phosphorescent afterimage racing across a retina, all that is clearly visible being the toe caps of knee boots striding in the scarlet corona of a headlamp. Then, even the red illumination switched off, the last steps, to carry on the final few hundred yards to calling distance of the roost tree, are accomplished in consummate darkness.

To be acquainted with the night is the soul of hunting the American wild turkey. The young moon set and the stars washed away before dawn, this is the hour of the hunt most vividly recollected, though it passes while looking not at the things that are seen, but at the things that are not. It is this one hour of the day that you desire most to be unceasing. Without the sun to refer to, time seems held not in amber but in obsidian, impermeable, a bit of immortality in the midst of Mississippi.

Nocturnal considerations, surely, for a nocturnal soul, but ones of an ultimately diurnal hunter. So you locate a seat in the duff of longleaf needles, back resting against the alligator hide of the pine, while the decoys are put out and the other two hunters find their own seats. Then you wait for the sunrise in perfect (or as near as you can imperfectly accomplish it) silence, hoping for the singing of the redbirds, the hoot of the owl, and the incensed gobble in retort from the limb of a tree, not far off.

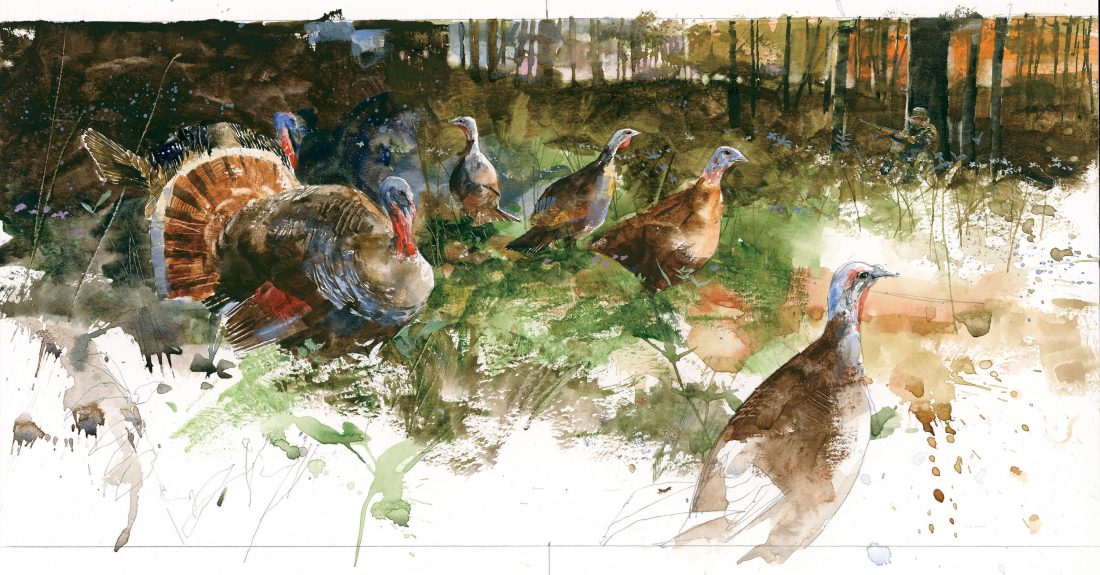

Before you spreads, still unseen, the carpet of a food plot, just now greening in the lately arrived spring. When you begin to see them, the woods around the plot remain mute testaments, leaving only the internal echo of musings to threaten distraction.

The saying of the Portuguese is that you plant pines for your children—and cork for your grandchildren. Longleafs are part of the long game. It is a pine that in recent times has had to grow in the literal shadow of the loblolly, in no small measure due to the unreasoning devotion of Southern authors to the beguiling consonance of the latter’s name. That, and the facility of the loblolly to achieve a size ready for harvesting as fence posts in a mere fifteen years, while it takes a longleaf a full two generations to be fit for more profitable felling as a telephone pole.

Not exactly a Bierstadt portrait of the forest primeval. It should be said that a million acres or more of the Magnolia State continue in public hands, yet the portion of it that survives as wilderness is no more than what that silver paring was to the totality of the waxing moon. Vanished are the groves of hundred-foot cypresses a thousand years old that filled the bottomlands when the pioneers came at the turn of the nineteenth century into the last most-wild territory east of the Mississippi, rolling their goods packed in hogsheads coopered from Virginia oak and hauled behind yoked oxen. Despite panegyrics offered in evidence of a fabled Eden (in the manner of combed-over real-estate developers down through the ages), what awaited most immigrants in what was in fact Indian country was a malarial hinterland teeming with savage beasts where hookworm, the “germ of laziness,” lurked.

White-tailed deer, black bears, red wolves, Alligator mississippiensis, panthers, banked clouds of green-headed ducks, detonating coveys of bobwhite quail, ivorybills still, venomous vipers in plethora, and wild turkeys severely outnumbered human inhabitants, particularly after the “removal” of the aboriginal peoples.

Here, close by Magee, between Jackson and the Gulf, the conditions were ideal for timber and cattle, if not cotton. Grain was grown, too, ground in the first gristmill to be built in the locale, in the 1840s. And, it goes without saying, double-bitted axes and thwart saws soon rendered towering forests into milled planks and stumps.

The limbless trunks begin to take on substance. The air is windless and velvety, but still without sound, as if in an auditorium awaiting the lifting of the curtain. There are even a few throat clearings and foot shufflings. Yet, no louder noise. It can seem interminable, waiting as the light climbs like the imperceptible upward sweep of an hour hand. Meanwhile, shotgun bolts are actioned, safeties set.

You hear the first birdsong now, a tremulous note. To your right and a little behind, Preston Pittman, five-time champion turkey caller (no need to give his physical description, as he is disguised behind camouflage), produces a soft yelp on a slate.

The virgin trees cut, the game could only follow, first the most rare, wolf and cougar, then the bear, almost—predators everywhere swiftly banished with the advent of civilization. The whitetail barely survived. In time, by the 1940s, even the turkeys were all but gone. Come the 1950s, new realizations about wildlife, and other matters, began to take root in Mississippi. What there were of turkeys were now transplanted and reintroduced around the state. From who knows what paltry few, the turkey population climbed, till today the birds number some quarter million.

The virgin trees cut, the game could only follow, first the most rare, wolf and cougar, then the bear, almost—predators everywhere swiftly banished with the advent of civilization. The whitetail barely survived. In time, by the 1940s, even the turkeys were all but gone. Come the 1950s, new realizations about wildlife, and other matters, began to take root in Mississippi. What there were of turkeys were now transplanted and reintroduced around the state. From who knows what paltry few, the turkey population climbed, till today the birds number some quarter million.

There came also a clearer recognition of the inherent value of longleafs and fire. You can burn a stand of longleafs the way votes are cast in Chicago: early and often. Fire creates more and finer habitat among the trees, to the benefit of all that walks, crawls, roosts, and flies there. And of the ones who hunt.

From the bottom below the food plot comes a tree gobble. Then farther back beyond Pittman, another tom calls out. Then a third, distant, out past the third hunter, Bobby Berthelot, of the National Wild Turkey Federation, equally indescribable as he sits tented in a full gillie suit, resembling a raked pile of green leaves. The gobbles continue, caroming around the woods.

Some will naturally wonder, about turkey hunting, WTF? (No relation, BTW, to the NWTF.) Why would sane adults dress ludicrously to sit motionless for hours with their spines against trees, sensation in their ischia deteriorating from torment to anesthesia, cradling shotguns awkwardly across their knees, waiting for the strutting appearance of an animal more commonly associated with a pop-up timer?

Saying it is indefinable would be too simple, if not simplistic. It is as definable as the impulse to cast a dry fly to a sipping trout, or to entreat a skein of ducks into a spiral culminating in setting into a spread of decoys. For all the ways we pursue game, from sweeping rows of harvested corn or patches of broomsedge, still-hunting the verges of timber to trolling for tuna in blue water, there are only so many that involve the genuine imitation of the animal. In that, we transmute ourselves from pursuers to the pursued. Those who profess perceiving Zen in the art of archery speak of being the target; and in a very real, practical sense, that is what takes place when we use friction to converse in the voice of an animal not even in the same taxonomic class. I may not be the walrus; but to hunt the wild turkey, I am the turkey. At least to the bird’s satisfaction.

Preston Pittman is one to give such satisfaction. His quintet of championships is not so much the result of an indomitable spirit of competition as a natural outgrowth of an immersion in the world of the wild turkey, dating back to a childhood spent in the turkey woods, beginning at a time when his index finger was too short to curl into the trigger guard of a shotgun. He learned to shoot with the tall finger of his right hand, a manner you can see he effects to this day. He did not have to go out in deliberate expedition to learn the calls of turkeys; he merely had to be attentive to what was around him, and absorb.

His pot call reaches to the nearest gobbler, the one that flew down into the timber below the food plot. Five thousand acres surround this turkey, a mix of loblolly and longleaf, black-oak bottoms, and dogwoods starting only now to flower into sprays of porcelain white. For all its perceived ungovernability, there remains something manicured about this land, something telltale of a place attended to.

With the brown 870 he calls Feed the Children across his knees, Pittman is gradually working his way through his entire repertoire of calls, using slate and box and diaphragm. The woods speak with gobbles answering back from all around. (At one point a gobbler walks to within sight of Berthelot, but at the wrong angle and out of range, stretches its neck to peer for a moment, then turns and walks away.) With the morning light a crescendo is reached, then begins to recede.

Pittman starts calling with his voice alone. The physical demands of this are extreme. It can lead blood vessels in the vocal cords to burst, so it can only be done as a last resort, and only for a limited amount of time. It’s like a pitcher going to his fastball, though he knows he will pay for it by retreating into the clubhouse for hours, soaking his elbow in a bath of ice.

Pittman’s calling, so perfect it carries a sort of orchestral quality, draws excited responses. But no birds are drawn in. It seems obvious that with the exception of one lone scout, the turkeys are hung up. Your mind can think of a host of reasons. The late spring, as evidenced by the dogwoods just now coming into bloom; the weather—it has been raining for days; the proximity of live hens, wishing to mate; or the sheer universal contrariness of turkeys, respecters of no hunter’s hopes. And as you sit, you hear the chorus of gobbles fading off.

The woods are hushed for long stretches as it grows longer in the morning. You start to shift more, less rigorous in your attention to silence.

There is one sound. It is like a heavy buck splashing out of a creek. It takes time to realize a dead tree fell in the sodden woods. Hard to imagine a tree old enough to have died in these woods, though maybe it was lightning-struck. Reminding you that not for all the husbanding and culturing of this land can true wildlife be compelled to come into gun range, if it does not take a mind to.

There is one sound. It is like a heavy buck splashing out of a creek. It takes time to realize a dead tree fell in the sodden woods. Hard to imagine a tree old enough to have died in these woods, though maybe it was lightning-struck. Reminding you that not for all the husbanding and culturing of this land can true wildlife be compelled to come into gun range, if it does not take a mind to.

Woods like these are a hand-carved board and chessmen, upon and with which the game is conducted. The live part, the one of sentience and movement, is not played by them, but through them. No matter how artfully crafted the landscape (and consider that the word landscape, when it came over into English from the Dutch, first referred to a picture of the land, an artistic creation, before it was applied to the actual view of a natural vista), what occurs in it resists, utterly, all efforts at art. Certainly, a tract can be laid out in an enclosed way to ensure that game will be killed upon it. What can never be done is to fashion a patch of land with the object of guaranteeing “genuine” hunting on it. The best that can possibly be done is to shape an environment that is the most inviting to wildlife, and then leave it up to the animals. Which is what Mississippians, at least these Mississippians, have done.

There is a way of telling time here without watch hands: When the sun climbs high enough that the light no longer spangles through the orb-weaver webs, but leaves them dried and removed from sight, the saying, not from the Portuguese but of local origin, is that it is time to piss on the fire and call in the dogs. You catch sight of Pittman gathering himself to stand, as Berthelot resumes human form from out of leafy matter. Blood is stamped into feet, and knees creak as a torso is levered back into an erect posture. Whatever needs to be is gathered up from the ground, and shotguns are slung on shoulders. Pittman, Berthelot, and you draw together and start to walk out in the slanting light over the brown bed of needles, among the crackleware bark of the pines.

The gobblers are silent. The woods have spoken.