When I was a child in the declining days of the solidly segregationist South, when Jim Eastland was still a Mississippi senator and Herman Talmadge was his Georgia counterpart and George Wallace was governor of Alabama (the list of similar, ahem, “statesmen” goes on and on—and on), there was an extremely popular license plate containing the message “Keep your heart [with an image of a splashy red heart subbing for the word] in Dixie, or get your ass [garish illustration of donkey’s behind] out!”

Now, I hated that thing even before I was old enough to grasp the offensiveness of its meaning, primarily on aesthetic grounds. It was super tacky, and I knew the noble donkey (otherwise known as Equus asinus and already among my very favorite animals) did not deserve to be used in such a way. But the long-suffering ass, which was first domesticated around 3000 BC and has been used as a working animal ever since, is a beast of burden that has borne far more than its share. I recall an image of Talmadge, the staunch segregationist governor and senator whose Georgia reign lasted from 1948 to 1981, rather stiffly wearing a suit and tie astride a donkey. He was finally banished from political life after his second wife, Betty, testified against him during a Senate investigation into a financial scandal in which he was found to have accepted substantial reimbursements for official expenses not actually incurred. Betty, whom he had married when she was eighteen, was not Herman’s hugest fan. When they divorced, she accused him of “cruel treatment” and “habitual intoxication,” but in apparently happier times, as First Lady of Georgia, she and Herman hosted lavish parties at their plantation in Lovejoy, where Betty was an enthusiastic slaughterer of pigs. Upon arrival, guests were greeted by soldiers in Confederate gray, Dixieland banjo players, and a pet donkey named Assley Wilkes. Take your pick about which is the most odious, but I’m going with Assley. I felt the same way about his namesake the simpering Mr. Wilkes as my man Rhett Butler did. No self-respecting animal deserves that moniker, especially not in that hideously cutesy version.

Donkeys have also been consistently derided as stupid and stubborn. Not so. They are, rather, intelligent and cautious, possessed of a healthy sense of self-preservation—their big, thoroughly adorable ears afford them excellent hearing so they are aware of danger way ahead of most creatures. Their so-called stubbornness, then, turns out to be an asset, a fact Andrew Jackson was smart enough to capitalize on. During the 1828 presidential campaign, supporters of John Quincy Adams called him a “jackass.” Jackson ran with the comparison, putting donkeys on campaign posters and highlighting his “stubborn” nature as a weapon in his battle against corruption and elitism. By the 1880s, with the help of the political cartoonist Thomas Nast, the donkey had become the unofficial symbol of the Democratic party.

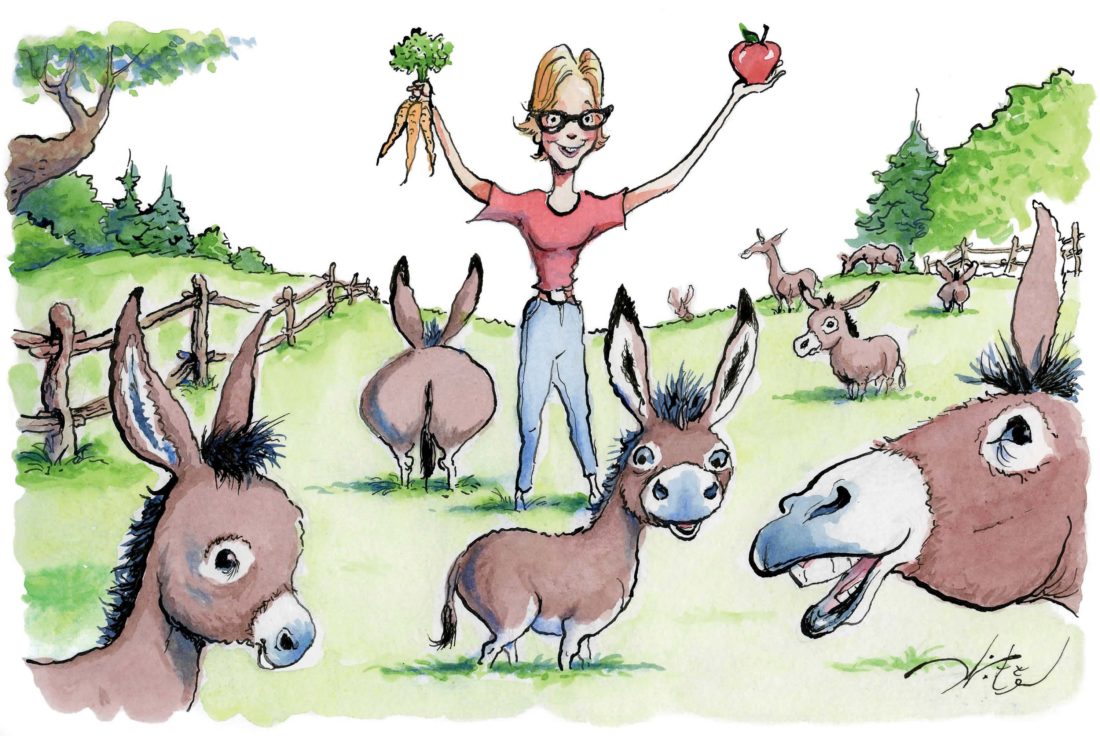

The Scots, who know a thing or two about a lot of things (including my favorite whiskey in all the world), are smart enough to use donkeys in Scottish heraldry as symbols of humility and patience. Exactly. And let’s not forget Christ his own self riding into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday in “lowly pomp” astride the humble beast. How could anyone gaze into those liquid brown eyes and not immediately recognize the donkey’s finer qualities? When I was on my first African safari, our group decided to choose what today would be dubbed our “spirit animal.” I chose the antelope because I felt such empathy, as though the creatures could look inside me and read my very soul. On home ground, it’s a donkey, hands down. For the last ten years or so, I’ve passed a seed barn in Chatham, Mississippi, where two donkeys and a black-and-white paint horse are kept. Recently, I’ve been making the trek on purpose, armed with bags of carrots and apples just to commune.

I’ll keep visiting my pals, but now I realize I could avoid the twenty-five-minute drive and install some of my own four-legged friends in the pasture across the gravel road from my new house in the Delta. I will have to rent or buy the space, but it will be worth it to wake up to the sight of my beloved donkeys, the odd horse, and a handful of mules (the offspring of the first two). I may even indulge in a long-held fantasy about freeing the sweet but miserable mules that pull carriages of overweight tourists around New Orleans’ French Quarter in the hot sun. They suffer such indignities as wearing plastic “straw” hats festooned with flowers while listening to the driver/“guides” get pretty much every piece of New Orleans history wrong. Once, while residing on the lower end of Bourbon Street, I went out to get my mail only to find a self-liberated mule on the run, cheered on by the gathering crowds on the sidewalk. He was hauling ass (an extremely useful description, and here, only a half bad pun), his harness sending up sparks as it scraped the pavement. It was a hell of a sight, and while I prayed he’d make it to safety in a field somewhere on the other side of the levee, I feel sure he was caught and pressed back into his dismal duty.

So, the pasture it is then. I will free some mules, buy a horse, collect some gorgeous long-lashed donkeys. I’ll make like the St. Francis of the Mississippi Delta, though since I can’t quite pull off the saint part, perhaps I’ll go with Lady Julia of Asinus. Anyway, I’ve a history with this particular piece of land that goes way back. Our neighbor Mr. Smith, who owned what were then hundreds of acres of pastures and fields surrounding the house I grew up in (behind which my current house stands), kept some cows and a big old bull back there. Since Mr. Smith was not so good at maintaining his fences, the bull escaped into our backyard, walked out onto the flat swimming pool cover, and promptly fell through it. It was three days before he allowed himself to be led up the steps at the shallow end, which, it must be said, demonstrates no small amount of stubbornness. But you know, he was traumatized. Several years later in the same pasture, I kept a horse named Hi Joe, who, when I was not riding him, did duty as a literal shoulder to cry on. In the winter I’d bundle up and lie down on top of him in the barn, weeping into his mane over various heartaches and reading novels that underscored my maudlin drama. Joe, a docile creature, did not seem to mind, and until I went off to boarding school and we put him out to pasture for good, he was my closest companion.

Unlike my late first cousin Frances, who was an accomplished rider, competing at Wellington well into her forties, I was not a serious horsewoman. When we were little, my grandmother bought Frances a fine chestnut pony named Key Biscayne, while I rode my riding teacher’s fat white pony, Mary Poppins. The pony and I won a few ribbons in our country horse shows, and I adored my teacher, Sue Chick, who later graduated me to a dappled gray horse named London Fog. But perhaps my greatest triumph was my first-place win as Lady Godiva in the costume class astride Mary Poppins. My mother outfitted me in a flesh-colored leotard, and I sported a waist-length ponytail made from at least a dozen blond Dynel falls purchased at Morgan & Lindsey, the local dime store. This piece of maternal ingenuity puts me in mind of the time Mama pinned Frances’s and my matching Florence Eiseman dresses together at the hip and sent us off to a costume party as Siamese twins (an event I’ve written about in more detail in this space previously). It never occurred to me how weird that might have been until I proudly told a friend of mine about it just a few weeks ago and he gave me a look that can best be described as What??? And I hadn’t even told him about impersonating a naked English noblewoman at age six.

As usual, I digress. Let us return to my dear friends the donkeys. They are even useful when they don’t carry packs in third-world countries. While they may not deserve it, their name has provided some of the greatest and most varied epithets of our time, especially when paired with such words as hat and, well…there are a lot. The insane Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez once said to George W. Bush, “You are a donkey, Mr. Danger,” but horses are not spared either. As Secretary of State Dean Acheson once said of Lyndon Johnson, “A real centaur: part man, part horse’s ass!” One of the countless funny lines uttered by my friend the inimitable Howard Brent involves a horse, but the behind in question is his own. “That horse threw me up so high, birds were building a nest in my ass before I even hit the ground.” And then there are the mules, also erroneously tagged as stubborn—among their many exceptional qualities are hardiness and longevity. There’s a passage in Andrew Lytle’s short story “Jericho, Jericho, Jericho” in which one of the characters insults the protagonist’s fiancée, who comes from the “new” industrial city of Birmingham rather than the fine old agrarian South. “Birmingham,” says Miss Kate, “I’ve got a mule older’n Birmingham.”

But back to my pastoral—or pastural—pursuits. I might actually ride my new horse, in a wholesome, healthy way, fully clothed in jodhpurs or breeches and posting properly up and down or galloping along the levee. I have photos of my last riding expedition about twenty years ago and most involve my friends atop their mounts, putting on lipstick and drinking beer. There’s one of me passing my lit Marlboro to a fellow rider so she could light her own. The actual riding part is a tad hazy. But the donkeys’ mere presence will change all that. I’ll gaze at them and get all centered and Zen and ride the horse and feel good about the rescued mules. In this particular case, my asinine plan feels like the opposite of what that adjective usually implies. I can’t wait.