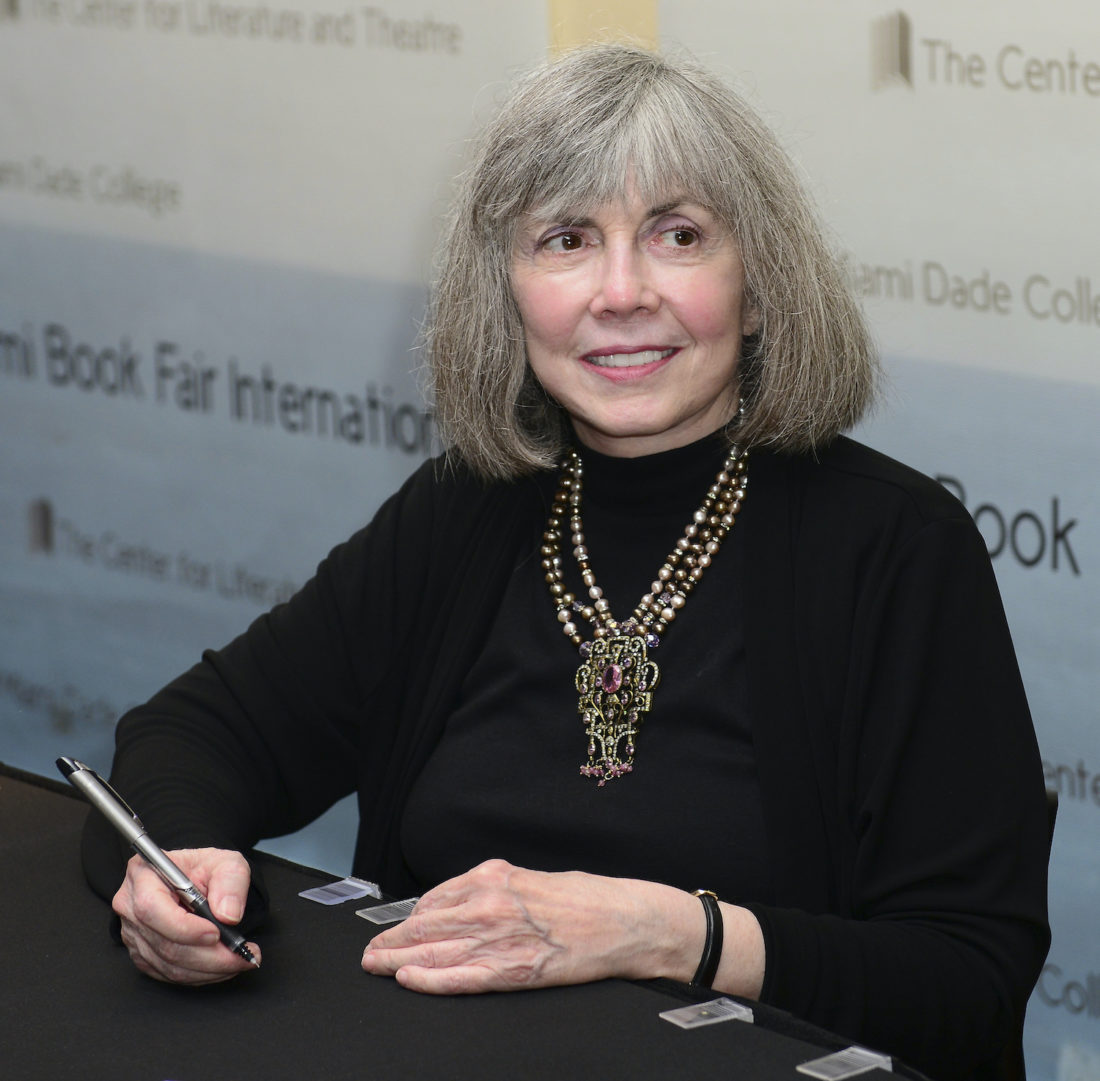

Editor’s note: Anne Rice, who died on December 11 at age eighty, was the author of more than thirty novels including the 1976 bestseller Interview with the Vampire. The supernatural fiction writer was a native of New Orleans, and the city influenced much of her work. Here, the author Constance Adler shares how Rice inspired her to move to, and write from, New Orleans.

Anne Rice’s novel The Witching Hour put a spell on me. The infestation occurred in New York, when my friend Colleen and I sat in the audience for an author talk with Anne. We were nuts about the Mayfair Witches and their uncanny ability to shape physical reality with their thoughts. When I lifted my head from that book, I felt my brain cells had been rearranged in a new order to see the world animated by an intelligence beyond ordinary logic. Anne Rice made the force of the unseen real. She was fearless in pursuing her own curiosity and crafted a stunning climax to The Witching Hour that held up a dark mirror to the Annunciation that a Catholic girl like me would never recover from. The word “magic” doesn’t go far enough to name her theme. Something more elemental and ancient undergirded her imagination.

The author event was informal. Anne and the interviewer chatted for an hour. Among her erudite remarks about the craft of writing, Anne also described how her native New Orleans informed her work. She mentioned coffee and chicory as an inspiration. With those words her voice dropped in pitch, her eyes half-closed, and she smiled secretively, as if savoring the taste on her tongue. I was a snooty, West Village brat. What did I know of chicory? Yet, I longed for this thing. She opened a new doorway—sensuality married to the cool work of the writer.

Anne also made a passing reference to the power of therapists, warning us to heed the potential for harmful enmeshment in such a relationship. After the talk, we waited to have our books signed. When my turn came, I asked Anne to elaborate on her comment. I was on the brink of breaking up with my (terrible) therapist but hadn’t found the guts yet. Anne told me that years earlier, before her great success, she was seeing a therapist who advised her that writing was making her miserable, and that she must stop writing and concentrate on being a good wife, if she ever wanted to be happy. It felt normal to have an encouraging exchange with this lovely, warm, smart woman—but really who else but Anne Rice would take the time to reveal so much to a needy young writer. Oh, and she fired that therapist.

Eventually, not only did I fire my own therapist, but I fired New York too. I packed up my life and moved to New Orleans in 1995. My home was a few blocks from Anne’s famous house on First Street, the setting for The Witching Hour’s extravagant plot points. I walked my dog in the evenings through that neighborhood. One night I was hit by a car because, rather than watching where I was going, I was gazing up to the attic window in Anne’s house, trying to envision bloodied, one-eyed Antha plummeting to her death on the flagstones. The driver of the car was not watching where he was going either; maybe he was bewitched by the house as well. In any case, he braked in time before causing serious injury. So, I was not so much hit by a car, as nudged by a car. The driver jumped out and apologized eloquently. They do that in the Garden District, apologize for hitting you with their car.

A few months after my arrival in New Orleans, Halloween rolled around. I had been hearing about this fantastic Memnoch Ball, launched by the Vampire Lestat Fan Club with the author’s blessing. Anne was hosting the party at her new home, the former St. Elizabeth’s orphanage on Napoleon Avenue that she had recently bought. (Anne acquired New Orleans real estate with as much appetite as she wrote books.) St. Elizabeth’s is an enormous three-story brick fortress, dating from 1865, that takes up the entire block with sprawling out buildings, a chapel, and a ballroom. It’s fronted by two white stone angels. Invitations were available to anyone—even desolate newcomers like me—costume required.

I had a short time to get ready. Fortunately, I happened to have a midnight blue, floor-length gown, cut on the bias, sort of Carole Lombard style, plus two long strands of pearls. Topped with my new mask of leather shaped into a grotesque beaky bird of prey, I was good to go.

The Memnoch Ball at St. Elizabeth’s in 1995 was attended by 6,000 of Anne Rice’s closest friends. Boy, was I embarrassed by my paltry costuming effort. The dazzling parade of vampires wore frothy lace and paisley velvet waistcoats, ivory-topped walking sticks, boned corsets, ribboned Louis XVI slippers, and eighteenth-century hair towers. A few had gone to the dentist to have fangs permanently cemented to their eye-teeth, such was their commitment to Anne and her fertile fictional world. There were fire-eaters, tarot readers, and a brass band followed by a second-line snaking through the grounds. The party was so crowded, I began to feel claustrophobic. At one point I was getting myself a drink in a first-floor room, and I glanced up at the ceiling, which sagged and bowed in time to the music above. The weight of too many passionate vampires dancing on these delicate 150-year-old floors was going to bring everyone upstairs crashing downstairs any second. I got out of there and went for a walk. Where was Anne? I wanted to see her.

I came to a cluster near the front door. When I peeked over the heads in front of me, I glimpsed a diminutive woman wearing a black wedding dress, a ball cap, and eyeglasses, her dark hair styled in a glossy pageboy, as she stepped out of her limo. I knew that Anne usually traveled by coffin to her parties. Tonight, I guess she opted for the mortal way. Everyone cheered when Anne’s husband Stan offered his open hand to his bride. They danced on the sidewalk, and kissed each other, before disappearing into the throng. Later Anne would stand on a stage to address her guests. I recall the warmth in her voice, her delight, when she exhorted us to embrace, “a truly romantic vision of life, where there is room for all the creative outcasts.”

Even though Anne Rice moved away from New Orleans years ago, when we learned of her death, something departed our city, as well. A poof of gas escaped the freak fun balloon. New Orleans is a bit smaller now.

Anne Rice accomplished a lot with her time and her talents, but one of the most noteworthy and perhaps least lauded was that she made people feel welcome. She opened her home. She answered the phone. She responded to serious questions from anxious strangers with a serious answer. She also gave good advice. To wit: when someone is giving you bad advice, fire that person. The second part I take from her example: Follow the thing that unnerves you, follow it far and into the dark, until it leads you someplace exhilarating, gorgeous, splendid. Good night, Anne.