Ralph Waldo Emerson never met the Slim Duck. He never met Gray Dude or Ginger. And he certainly never crossed the great American West in a ’67 Barracuda convertible. But had RWE experienced anything akin to making a road trip with a bewitching heartthrob like the Slim Duck, he might have tempered his opinion about traveling being a “fool’s paradise.”

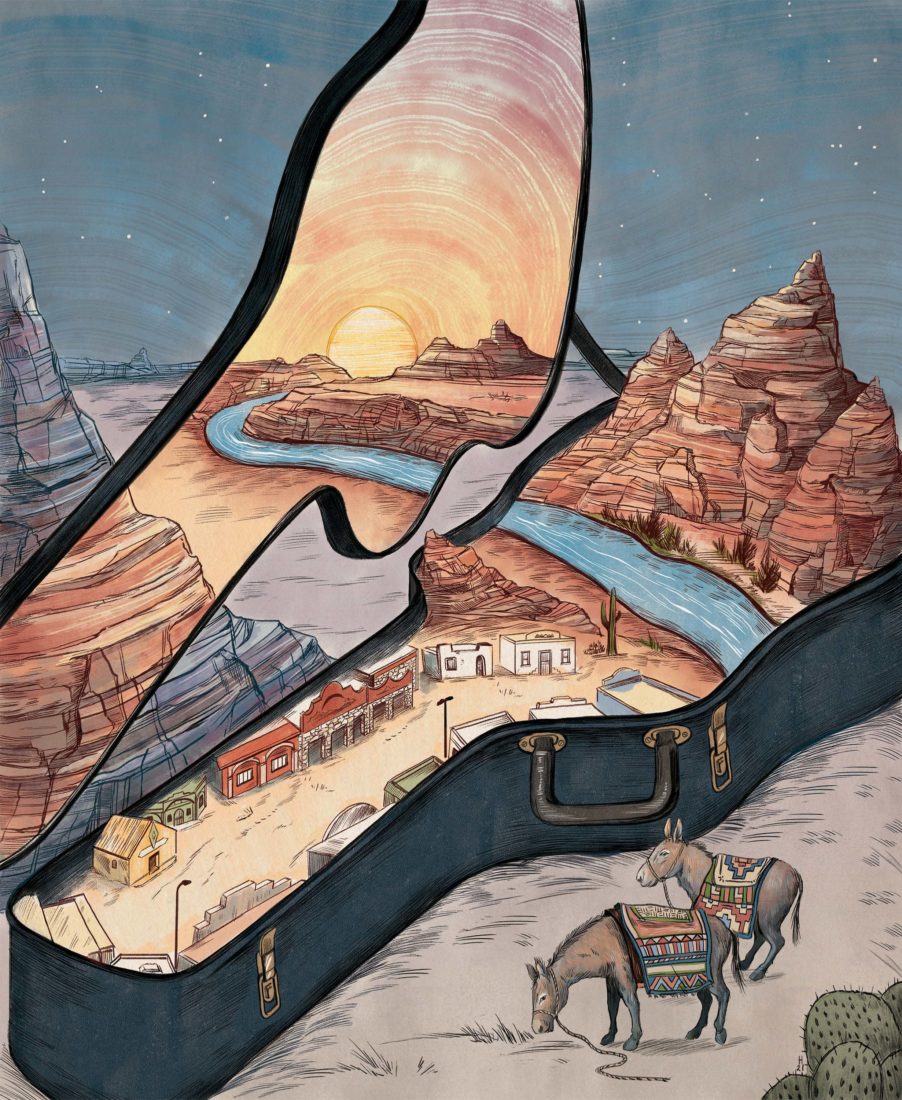

If traveling is a fool’s paradise, then hand me those sunglasses and pass the beer. I’ve been a fool for traveling since the last quarter of the twentieth century began, and I made my virgin road trip to Los Angeles with the Slim Duck, her black Lab, Ginger, and her surly African gray parrot, Gray Dude. This was my first adventure born of reckless abandon. The Duck, a ravishing and fearless freedom fighter, threw her compass to the wind and put her barefoot fun locator to the accelerator. Along the way, we experienced everything from breakdowns to break-ins; from sleeping in the car to cantina bar fights to camping under the desert night sky with a zillion stars. Our L.A.-or-bust interstate expedition gave birth to a lifetime of wanderlust. Moreover, our junket gave me my first glimpse of the vast Far West Texas land known as the Trans-Pecos.

A dozen years, a bountiful marriage, and enough gigs to pay the bills later, I was perched on the staircase landing above the San Antonio River, idly watching a party boat full of tourists float the day away. It was a surprisingly cool afternoon for summer in South Texas, and the River Walk was bustling with smiling faces and laughter. I was lost in thought when I felt a tap on my shoulder. I turned to see a small man who smiled and addressed me by name. I had no idea who he was. I don’t recall the exact interaction, but we found a rhythm to our conversation. I casually told him how my wife, Kathleen, and I were headed to Chisos Mountains Lodge in Big Bend National Park. His face lit up like the neon sign on San Antonio’s legendary Mi Tierra restaurant.

John, my new stranger friend, grabbed my hand and without any preview to his sales pitch, whispered one word, “Boquillas.” He went one step further: “Ask anyone in Big Bend how to get there. If you go, you’ll remember it for the rest of your life!” I was somewhat stunned and starting to get that “where is the exit?” feeling in my gut. I slowly slid my hand from his clammy grasp and walked up the steps. When I reached the top, he hollered, “Hey, you’re gonna write a song about it!”

Well, hell. What Gordon Lightfoot song did this guy crawl out of? How did he know me and what was the name of that town that sounded like a breakfast taco?

On our way to the Trans-Pecos and Big Bend, I gave Kathleen an abbreviated version of my afternoon rendezvous with John Stranger and suggested it might be worth investigating. Kathleen, who is always game and the most we-should-have-done-it-yesterday person I know, agreed. We jettisoned our hiking plans and set out for our new destination the following morning. After several false starts, a few wrong turns, and one photo shoot with a dead rattlesnake, we found the lost landing of Boquillas. That is to say, the sandy knoll that drops off into the Rio Grande.

The town of Boquillas, on the Mexican side of the river, is a border town like no other. It was a village where time seemed to stop in the decades somewhere between the Roaring Twenties and World War II. Our first indication of any chronological aberration was the uninspiring means of river transport. Resting on the sandy banks of the Boquillas landing was a small tarred and faded jon boat that had not seen an ounce of love since Andy and Opie left Mayberry. Sitting motionless and waiting patiently on a hard, grainy cross plank was our captain, Pablo. Kathleen and I stumbled into the boat, and after an embarrassingly butchered attempt at a Mexican greeting, I handed Captain Pablo two U.S. dollars and off we went. Almost simultaneously we left the country where time never ceases and entered a land where time never began.

Historically, Boquillas served as a mining town and a water stop for Mexican ranchers. Caballeros and outlaws alike enjoyed a bar, a livery stable, and a dry goods store. It looked like a Sam Peckinpah Western town—dusty, sparse, broken, and remote. As we floated, I was thinking about the movie The Wild Bunch and at the same time trying to gauge Kathleen’s reaction to our adventure when a metamorphosis began to permeate our collective consciousness. The combination of the time-travel crossing and the smell of fresh water on the desert air, coupled with the sepia-toned, dreamlike quality of our surroundings, was intoxicating. I turned and looked at my wife. She was smiling like a child in a room full of fluttering monarch butterflies. Her eyes shone with the magic of the moment. It made me laugh. Still does.

We made landfall and kissed the sunbaked sand (or did I snag the toe of my boot on the bow cleat and execute a hapless face-plant?). Twenty yards from the water’s edge stood a large tree. It was old and gnarly and looked like a spot where banditos once swung from the short end of a rope. At the base of the hanging tree sat an old man surrounded by a half dozen donkeys. I was still reeling from my linguistic flub with Captain Pablo, so I stuck with default communication skills. I held up two fingers and pointed at the donkeys, then threw my hands up above my shoulders. The old man flashed two open palms at me. I paid him ten bucks American, and he handed over two sturdy donkeys that made the half-mile trip into the heart of the town of Boquillas in a bit under an hour.

Our first commercial foray in Boquillas was a smeared-glass and wind-ravaged gift shop. It reminded me of all the crap that I loved and longed for when my parents took us to Piedras Negras or Nuevo Laredo on family vacation. How many onyx chess sets is too many? If one has a black-and-white bullwhip and a brown-and-white one, is it considered extravagant if one buys a red-and-white bullwhip? (“¡No te préoccupes, mijo! ¿Quieres este?” No problem.) The switchblades were on back order, however, so we moved next door to the cabana, where we met the man who was known as the unofficial mayor (or was it sheriff?) of Boquillas, Danny Hickle. He downloaded a taco bite of delirious color into our international odyssey. My experience has taught me that all worthwhile adventures include a human caretaker, and when it comes to road trip road managers, they don’t get better than the fugitive Danny Hickle.

From the outset, Danny came on a little strong for my taste, but he and Kathleen were on their way to becoming famous before I found the baño. By the time I returned, they were doing shots and making pinkie promises, with plans to turn Danny’s hovel into a political meetinghouse. I paid up, grabbed my beer, and caught up with the newly forged demonic duo in time to enter Danny’s dugout bunker—a postapocalyptic edifice of rock, asphalt, and chicken wire. Mezcal was passed around. Toasts were given. So many plans and promises were made that it would take five lifetimes to honor them. Finally, the excitement started to wane, and I was missing my donkey. We decided to bid Danny a fond “vaya con dios.” It was almost a clean exit.

Our Boquillas road trip ended with an epic finale. We were still in earshot of Danny’s house when he hollered, “One for the road?” And soon we were standing in what most considered to be the best bar in this part of Mexico. Icicle shelving lined the bar, sending cool slivers of dancing colored light throughout the room. A caballero brought his guitar and sang strange and beautiful songs. More beer. More mezcal. More pinkie promises and plans of reunion. There were tears but no regrets—except for the mandatory donkey curfew.

On the boat ride back to the U.S. side of the Rio Grande, Kathleen and I sat wrapped in a blanket looking up at the stars. In a somewhat rhetorical fashion, I asked her, “How did we get here, KK?” She reminded me about the guy I met on the River Walk, John Stranger. I thought about him for a minute and then told Kathleen the bit I hadn’t mentioned. The part of the story where John Stranger told me if we went to Boquillas, I’d write a song about it. Kathleen looked at me and said, “He’s right. You will.”