Much of what we now call “old-time” Southern music was on the verge of extinction when the Texas native David Holt arrived in Western North Carolina in 1969. So many of the South’s traditional music secrets—from how to play the banjo claw-hammer style to how to build hammered dulcimers—were locked inside amateur musicians, and those people were fast dying.

Holt decided to do something to preserve that knowledge, eventually devising and hosting UNC-TV’s Folkways, which began airing on Southeastern PBS stations in 1980, and Fire on the Mountain, which ran on The Nashville Network from 1984 to 1989. For both, he’d visit Southern musicians playing with under-heralded techniques and instruments—North Carolina’s Etta Baker picking guitar in the two-finger style characteristic of the then-little-known Piedmont blues, for instance.

The TV appearances were, in many cases, the only wider recognition these musicians and their methods received, and broadcasting them into peoples’ homes helped motivate the modern resurgence of acoustic Southern music. Virgil Craven, for one, was the last known player of the hammered dulcimer when Holt met him in 1976. Now there’s a crop of luthiers making hammered dulcimers for a passionate customer base of players.

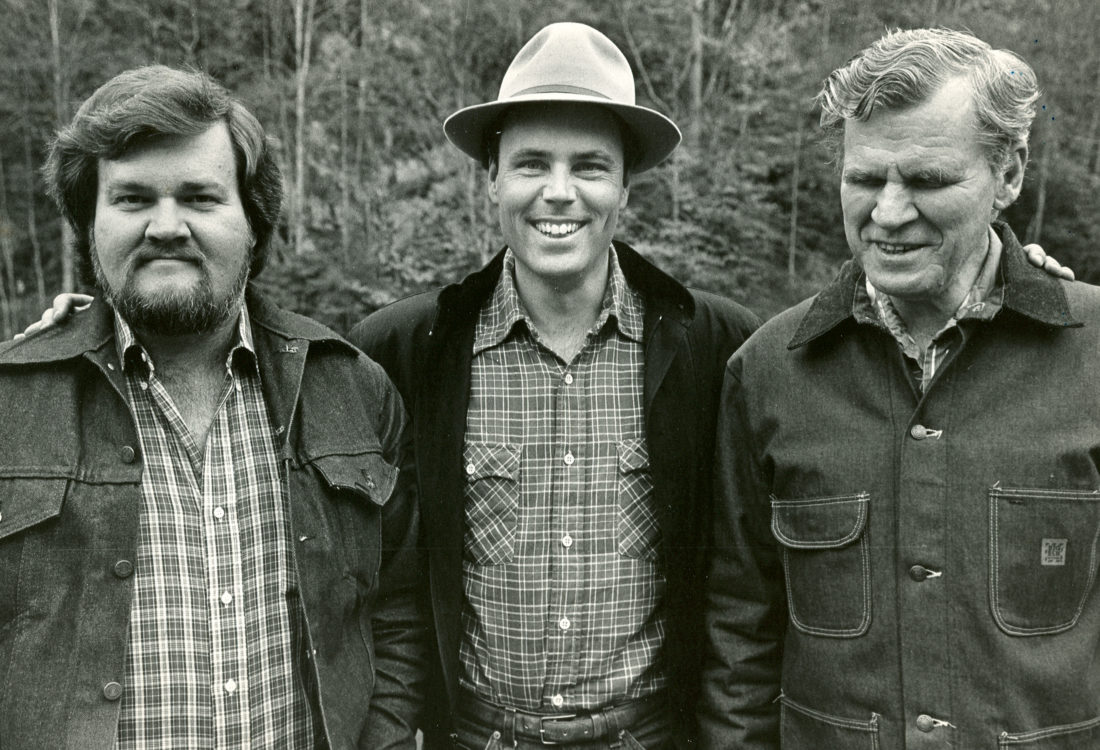

Over the years, Holt, who plays ten acoustic instruments himself, also toured with Doc Watson, winning two of his four Grammy Awards recording with the legendary folk musician. Now the walls of Holt’s home near Asheville are plastered with photographs of people he has met and featured on his programs, the latest of which—David Holt’s State of Music—is in its second season this summer on PBS. This time, the focus is on the future: how Southern music is evolving.

What originally sparked you to track down these forgotten amateur musicians?

I got jumped and beat up and left for dead when I was twenty-one, and that really changed my idea of what life is about—to “You got something interesting [you want to do], go do it now.” I grew up in Texas, so I got some 78s of old cowboy singers, and a fellow who collected them said, “You know, that very first cowboy singer ever to record [in 1927] is alive. He’s in Bryan, Texas, his name is Carl Sprague.” I went to Sprague’s house, and he spent the entire day with me. I still play the harmonica from what he showed me. I thought, “Man, there’s gotta be other people like that.”

How’d you end up in the Appalachians?

When I heard about the Southern mountains, that there were thousands of [these traditional] musicians alive, I came to Asheville and got a job as a sign maker. I did that for a year and just worked on [learning old-time] music every minute I had out of the job. What’s now the Asheville Citizen-Times did an article on me, and people started asking me to perform. I started doing it and realized I really liked getting in front of a crowd and trying to interest them in these older, odd traditions that I’d come across, and they seemed to enjoy it. By 1975, Warren Wilson College invited me to start an Appalachian music program, so that was a great learning opportunity for me to be able to get old-timers on campus to teach the students to play. I did that for six years.

Bluegrass shows and old-time folk shows have become popular with twenty- and thirty-somethings, even on the West Coast. Twenty years ago, you’d never see such crowds of people that age. What changed?

This music is all about community. It’s all about people playing together and having a rapport together. I think people are looking for something that has some solid gravitas, or seriousness, to it. I like to say these old [musicians] came of age before self-doubt was invented.

Linking the music and instruments with peoples’ personal stories has become a calling card of yours in your concerts and shows. What makes David Holt’s State of Music different from Folkways?

Folkways was all about North Carolina traditional crafts and music. It’s probably half crafts stuff and half music. David Holt’s State of Music is all about music and what’s starting to be a wider range in music from the Southeast outward. When I was doing Folkways, I was really looking for people who you probably wouldn’t have heard of unless you were really deeply into this music. On David Holt’s State of Music, we’re trying to have a mix of people who’ve already broken and then people who you’d never, ever see any other time. We’ll have Rhiannon Giddens, the Steep Canyon Rangers, the Kruger Brothers, and then somebody like Dom Flemons or Amythyst Kiah, who few have probably heard of.

What do you think about old-time bands bringing in electric instruments and fusing other musical styles with old-time to make new genres out of old ones?

That’s what I would consider Americana. I think that’s wonderful, all that goin’ on. I hope there are still a few people who will hang with the old music and keep it going, because it’s got a lot of power too. It always has changed, it’s always been changing. It’s never been static.

David Holt’s State of Music airs nationally on PBS. You can stream full episodes at PBS.org.