There’s a reason more than a million people flock to Biltmore Estate every year—it’s simply the closest you can get to a fairytale castle this side of the Atlantic. Constructed between 1889 and 1895, this colossal estate outside of Asheville, North Carolina, seems like a fantasy, but it is very real. The word ‘Biltmore,’ however, is pure invention. When it came time to name his estate, sophisticated bachelor George Vanderbilt combined ‘Bildt’—his ancestors’ Dutch surname—with ‘more’—the Anglo-Saxon word for rolling, open land, coining a charming name for what would eventually become an international tourist destination and million-dollar brand.

Photo: The Biltmore Company

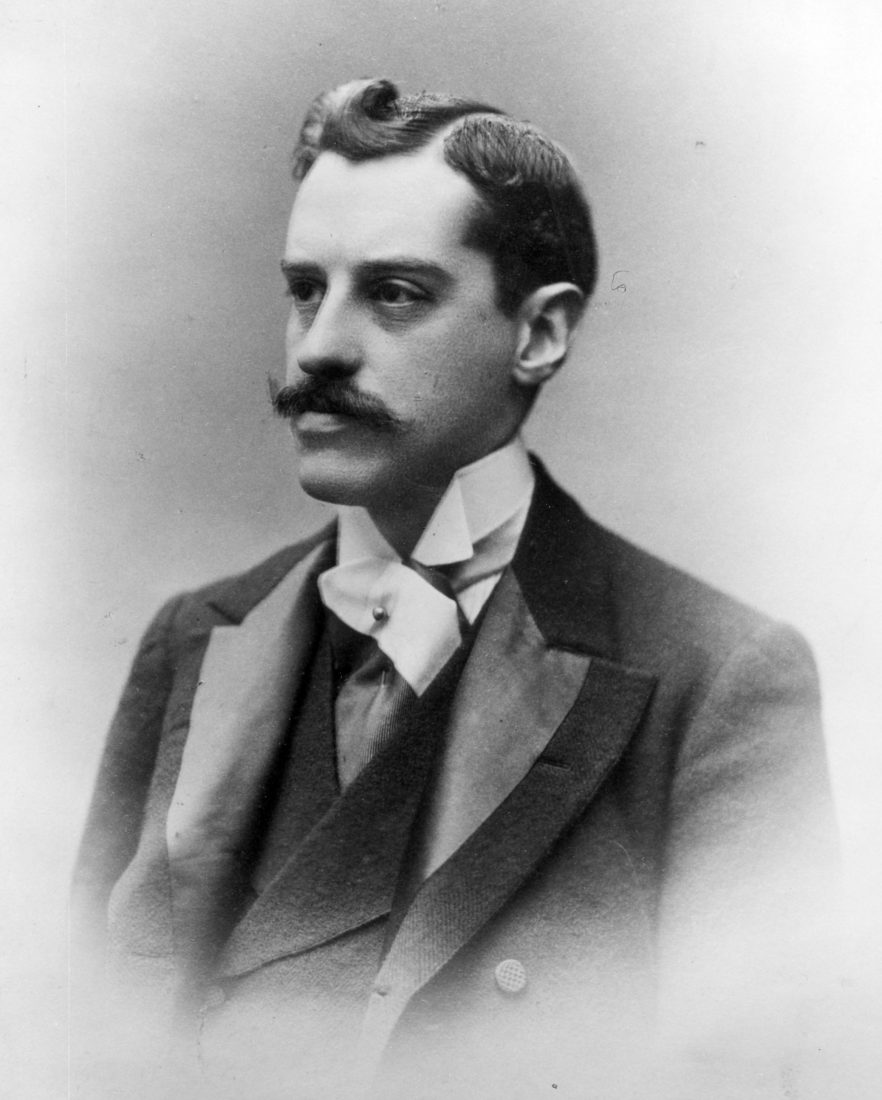

George Vanderbilt.

Approaching Biltmore, the largest privately-owned home in America, is not unlike approaching the great cathedrals of Europe. The scale of the east façade, bristling with gargoyles and clad with gleaming Indiana limestone, is staggering. Biltmore encompasses 175,000 square feet—35 bedrooms, 46 bathrooms, a cavernous indoor swimming pool, and an indoor bowling alley (among other charming amenities). Biltmore’s immensity is matched only by the thoughtfulness and attention to detail of the three men responsible for its design and construction: George Vanderbilt, architect Richard Morris Hunt, and landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted.

Biltmore first glimmered in Vanderbilt’s eye at the tender age of twenty-five. During a visit to Asheville in 1888, he looked out from the ridge where the house is now built and declared his wish to own everything he could see. (A lofty goal achieved by the time of his death.) While land acquisition began in earnest that year same year, Vanderbilt hired Hunt, an accomplished architect responsible for a handful of Vanderbilt residences in the Northeast. Vanderbilt and Hunt traveled together to England and France to gather design inspiration, paying particular attention to Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire and several sixteenth-century chateaux in the Loire Valley. The structure they realized together was a technological marvel at a time when indoor plumbing was rare—not just in Appalachia, but across America. When Biltmore opened in 1895, it boasted electricity, instant hot water, central heating, two elevators, refrigeration, an elaborate call system, and a brand-new invention—the telephone.

Photo: The Biltmore Company

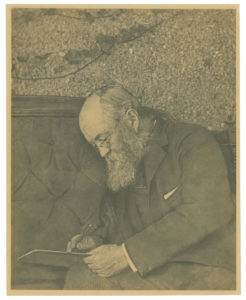

Frederick Law Olmsted.

When tasked with designing the expansive gardens and grounds surrounding Biltmore, Olmsted recorded his candid assessment of existing conditions as, “the soil seems to be generally poor. The woods are miserable.” A majority of Vanderbilt’s new estate had been poorly forested for some 200 years, “leaving the runts behind.” Olmsted and Vanderbilt worked closely together to design the winding approach road, formal walled gardens, picturesque retreats, reflecting ponds, and sublime tracts of planned woodlands. The estate was Olmsted’s final and most significant project, and his achievements stretch far beyond its gardens. Biltmore was first placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966, not necessarily because of the house, but because the estate is the birthplace of American forestry. Working alongside forester Gifford Pinchot, Olmsted and his team planted millions of trees on thousands of depleted acres, an unparalleled effort that led, ultimately, to the founding of the U.S. Forest Service. Before his death, Olmsted called Biltmore “the most permanently important public work” of his career.

Photo: The Biltmore Company

The Biltmore’s Italian garden.

Biltmore is a fantastical structure, and the contrast of building a Gilded-Age chateau amid the historically impoverished Appalachian Mountains still seems an incredible leap of faith, some 120 years later. George Vanderbilt’s legacy isn’t the house, although it’s certainly easy on the eyes; it his dedication to improving the lives of the hundreds of people who lived and worked at Biltmore above all else.With a dairy farm, a railway station, a church, and a school, the estate functioned as a self-supporting agrarian village, and provided jobs and a regular wage for people who desperately needed it. Generations of people in Western North Carolina benefited from Vanderbilt’s philanthropic vision—a tradition that continues to this day.

Photo: The Biltmore Company

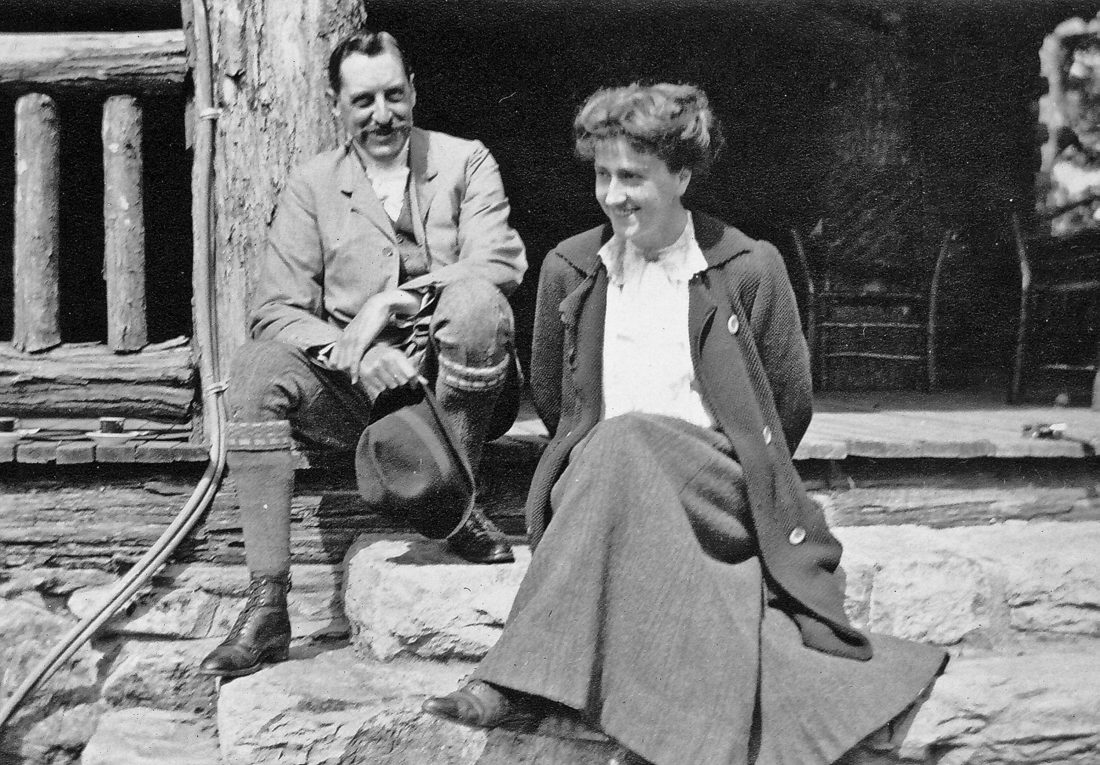

George Vanderbilt and Edith Stuyvesant Dresser.

In 1898, three years after moving in at Biltmore, George married Edith Stuyvesant Dresser. Their daughter, Cornelia, was born in 1900. George Vanderbilt died suddenly in 1914, leaving his wife and young daughter to shoulder the burden of the enormous estate and the livelihoods of those who depended upon it. Edith and Cornelia survived by selling portions of the land surrounding the estate and continued to run Biltmore Farms at a profit. Cornelia’s son, William A.V. Cecil, transformed Biltmore from a struggling private home to a self-sustaining tourist attraction in the mid-twentieth century. He added parking, restrooms, and cheerful tour guides, and worked tirelessly to promote Biltmore and the Asheville area as a tourism destination. When asked about his determination to reverse the fortunes of Biltmore, he said, “If you ever want me to do something, just say ‘It can’t be done.’ Everyone told me it couldn’t be done, so I just stuck my feet in it and said, ‘We’ll see about that.’ And that is what motivated me.” The family turned their first profit in 1969—$17.

Click to go behind the scenes at the Biltmore Estate

Photo: The Biltmore Company

The tapestry gallery.

In 2018, Biltmore continues to thrive. The Estate is still owned and operated by the family (William Cecil, Jr. is the CEO), and a dedicated museum-services staff oversees the structure, collections, and landscape. These twenty highly-skilled curators, conservators, and collections managers ensure the preservation of the most important resources at Biltmore, and their perspectives on the house and gardens is unique. Quite often the best people to ask about a historic site are the people who periodically clean parts of it with a toothbrush.

These are five things they recommend you look for on your next visit.

#1: PRINTS

Vanderbilt was known as one of the world’s great collectors of etchings, engravings, mezzotints, and wood cuts, and he amassed an important collection over his lifetime. There are 1,228 prints in the fine art collection at Biltmore. In a house with four acres of living space to furnish, perhaps Vanderbilt economized by purchasing prints instead of original paintings? “We’ll never know,” says Collections Manager Laura Cope, with a laugh. “He was careful in his collecting,” she adds. “Patterns emerge, and you can tell what he was most interested in.”

The print collection is displayed throughout the house, and works are often hung in places where visitors can get quite close to them to appreciate details. “Most guests walk by and miss them,” says Chief Curator Darren Poupore. “Once you stop and look, you realize how important they are within the aesthetic of the house and how they were used to furnish rooms.” In fact, Vanderbilt named certain rooms after artists and subjects in his prints. Print collectors in the nineteenth century focused on series of prints, and Vanderbilt was no exception. He was fascinated by the changes between series, and deliberately collected examples of them. In the Claude room, look for two seemingly matching prints (“the Enchanted Castle”) hung side-by-side. This was a deliberate choice by Biltmore’s Curatorial staff; an invitation to look closer and see if you can spot the differences.

Photo: Courtesy of the Biltmore EstateThe Biltmore Company

The Claude room.

#2: INHERITED FINERY

George Vanderbilt spent years acquiring fine and decorative art to furnish Biltmore, but there is a small group of objects he inherited from his grandfather, Cornelius, and his father, William Henry. The third floor living hall is the best place to find these inherited and, in some cases, repurposed objects brought to Biltmore from Vanderbilt properties in the northeast. Look closely at the display cabinets and bookcases in the third floor living hall–they are repurposed from cabinets built by Herter Brothers for George’s father at 640 Fifth Avenue in New York City (now demolished). If it’s a slower day in the third floor living hall, ask the host to see a reproduction copy of a book published in 1883 called Mr. Vanderbilt’s House and Collection. It includes detailed interior shots of the demolished Fifth Avenue mansion, and you can easily spot the pieces saved and brought to Biltmore. Also, if you find yourself near the tasting rooms at the Biltmore Winery, be on the lookout for a stained-glass window by genius glass artist John La Farge. Nine were salvaged from Fifth Avenue, but this is the only one you can examine up close (perhaps before you visit the tasting rooms).

Photo: The Biltmore Company

The third floor living hall, which features bookcases made using columns salvaged from another Vanderbilt home.

#3: HIDDEN GARDEN FEATURES

“The cactus room [at the conservatory] is my favorite place on the entire estate,” says Leslie Klingner, Biltmore’s Curator of Interpretation. As the curator responsible for Biltmore’s impressive schedule of blockbuster exhibits, Klingner has perfected her break times, and knows exactly where to escape for a quiet moment.“When I walk in there, I feel like history is literally alive,” she says. If you have enough time, walk from the conservatory down to the boathouse, a secluded and often overlooked stopping point by the banks of the lagoon. Olmsted designed the gardens leading down to the lagoon to be transitional—from the most formal to the least. In half an hour’s walk, you move from the walled garden with its razor-sharp rows of springtime tulips to the sublime bramble of the lagoon. “[It] makes me feel like I’m in Central Park or a private camp in the Adirondacks,” Klingner says. For guests with mobility concerns, a new hop-on, hop-off tour will deliver you to the lagoon and pick you back up again.

Photo: The Biltmore Company

The conservatory.

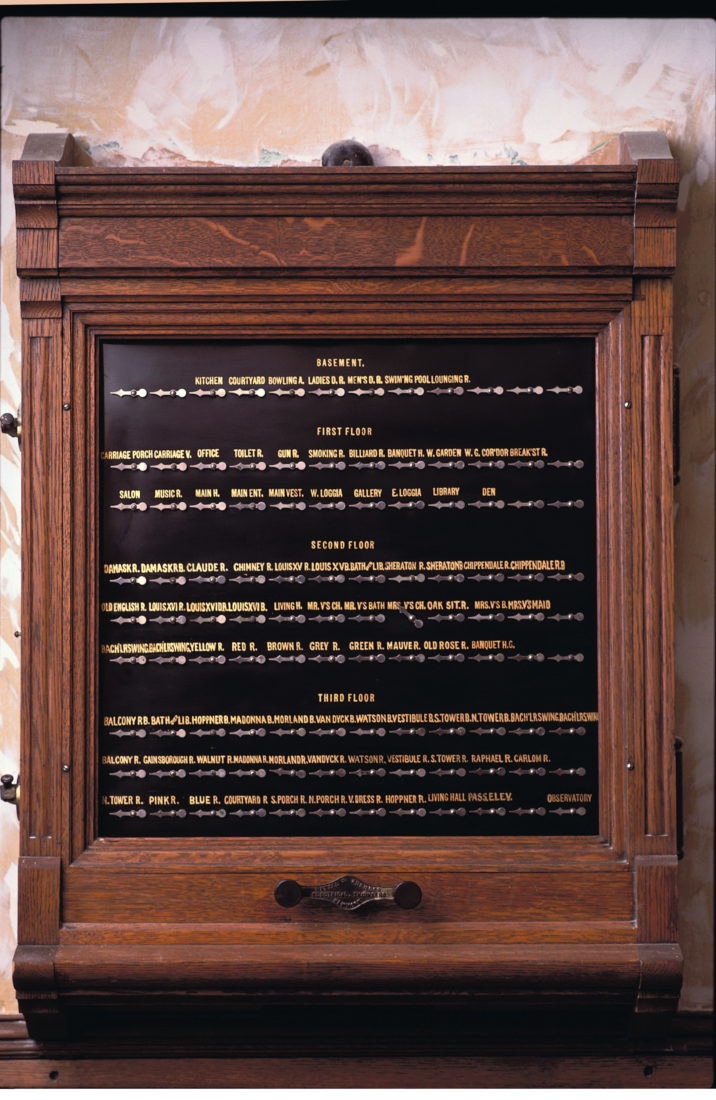

#4: HOW THE HOUSE ACTUALLY FUNCTIONED

With so much splendor to see at Biltmore, it’s easy to forget how the house was lived and worked in. Nearly every room has a servant call button, and if you attend a behind-the-scenes tour, you can see the servant call boxes. This is a great way to understand how the house operated more or less like a hotel, and in a very efficient way. According to Darren Poupore, the two-story butler’s pantry will be added to regular tour in February 2019. He calls it the “central nervous system of the house.” Walking through the kitchens is an experience, and it’s interesting to see the technology employed for the first time—electric lights and refrigeration! Ask to see a reproduction of the 1904 Menu Book; it gives incredible insight into what was happening below stairs—the type of food, how many courses, and how intimately involved the Vanderbilts were in planning every detail of their entertainment schedule.

Photo: The Biltmore Company

The kitchen.

1 of 3

Photo: The Biltmore Company

The servant call box.

2 of 3

Photo: The Biltmore Company

A dumbwaiter in the main kitchen.

3 of 3

#5: GEORGE AS A CHILD

If the meteoric rise of the Vanderbilts in the nineteenth century was a spectacle from the outside, imagine what it was like for George Vanderbilt to grow up at the center of it. To the casual observer, Biltmore might seem like the Gilded Age run amok, but if you consider George Vanderbilt as a child, his choices become more understandable and even endearing. Look for a pair of paintings on the second floor that depict George as a young child. The first, entitled Going to the Opera, hangs in the hallway outside of Vanderbilt’s bed chamber. George’s father, William Henry, commissioned Seymour Guy to paint the intimate scene in 1873, and it provides a rare glimpse of George as a child, surrounded by his family. “There’s just so much of his personality in this picture,” Klingner says. “He grew up in a time when his father was retiring from business, so he was surrounded by connoisseurship. He is literally at the center of it, absorbing everything.” As you walk into the Oak Sitting Room, look carefully for the portrait of a young George with his sister, Lila, and brother, Frederick. George is the one with the sweet pink cheeks and little pink bow tie. “We don’t know where it hung originally,” Klingner says, “but we put it here because it is a private family space. There is so much going on in this room, I think people don’t see it. It is such a special glimpse of George as a little boy. Parts of the core of him are already developing—those parts that will inform the development of this house.”

Photo: The Biltmore Company

A portrait of George (left), Frederick, and Lila Vanderbilt.

Click here to see more photos from the Biltmore Estate

Lauren Northup is Director of Museums at Historic Charleston Foundation