Shelby Lee Adams’s uncle was a country doctor in the remote hollows of eastern Kentucky. During his high school years, Adams often traveled with him as his ersatz medical assistant, helping set broken bones, patch gunshot wounds, and treat mine-accident traumas. It was and is coal-mining country, and Adams saw the poverty and suffering the people—“my people,” he calls them—endured.

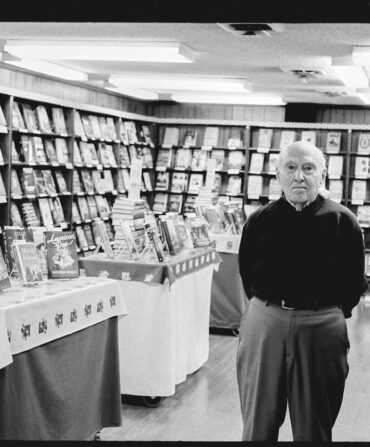

“I grew up with a different vision,” says the sixty-one-year-old photographer, whose body of work—some ten thousand images from Appalachia—is represented in the permanent collections of museums across the country and internationally. “I’m trying to put a little light in some darker areas.” His fourth book of portraits, salt & truth, was recently released by Candela Books, and selected images will go on display beginning in March at Louisville’s Paul Paletti Gallery.

Adams knows dark. He likes to quote Cormac McCarthy, and in the narrow side-winding valleys of Kentucky, he’s had guns pulled on him. (“They’re just testing you,” he says.)

His uncle’s patients were his first subjects, and he treated them all like family, collaborating with them on the shots and giving them prints afterward. His reputation spread throughout the hills, and over four decades he established deep ties to the families he photographed. Take Louverna, who lived in Lost Creek. Adams had been photographing in the area since 1989 but had never met her. Then her brothers flagged him down and told him that she wanted to talk to him. Adams went to see Louverna, who said she was very ill and wanted him “to make my picture.”

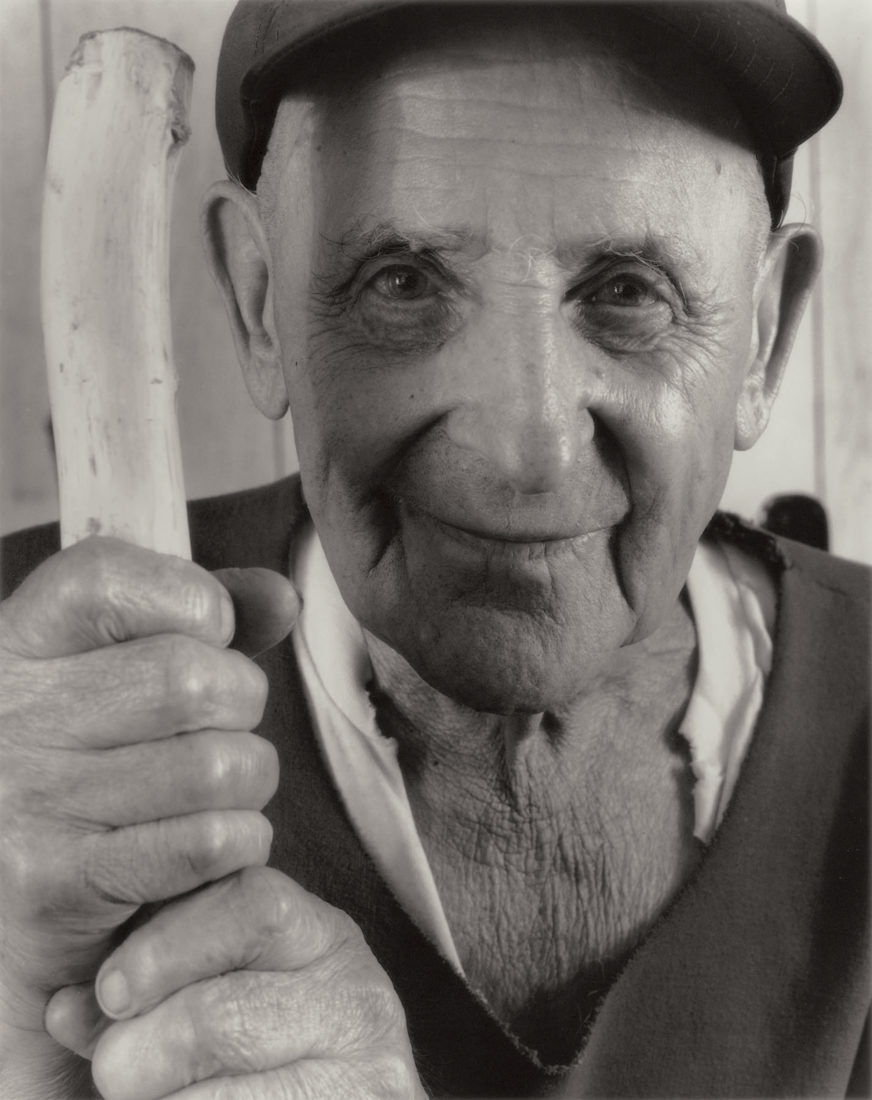

Photo: Shelby Lee Adams

“Louverna, 2008”

“I knew she meant right then,” Adams says. “It was dark. I was tired. Didn’t want to do it.” But he did, setting up his 4×5 tripod mounted view camera and lights and shooting her portrait on the porch of Gate Way to Heaven Church, where he had once photographed her father. In the picture in salt & truth (“Louverna, 2008”), her unflinching gaze penetrates us through the lens of Adams’s camera.

Adams took the shot of Louverna on a Thursday. On Monday, her brothers called to tell him that Louverna had “passed.” The family then asked him to photograph her funeral. “When you do a mountain funeral, you do all the different family relations around the coffin,” he explains. “They’ll hang them with family, wedding, and military pictures.” On Thursday, he took another picture of Louverna, this time in her deluxe white casket, surrounded by bouquets of flowers and four clean-scrubbed hardscrabble brothers.

“It is the spirit of the mountaineer living in the hollers that motivates and interests me,” he writes in the new book. “The culture is multilayered in expressing the fullness of life.” Indeed, poverty, deformity, and aging sit side by side with kinship, music making, and animal husbandry as themes that emerge in the work. While some of the photographs may strike outsiders as being uncomfortably intimate and bleak, for Adams and his subjects, they reflect the pride they share in the often tough mountain way of life.

To Adams, his work and his relationships with the people of the region are inseparable. The camera does not divide but unites them. “It’s really personal to me,” he says. “I don’t have an agenda. What’s kept me going and why I’ve done this for thirty-six years is because I’m still exploring the place I grew up in. It’s not a documentary political statement.”

“These people are worthy of being seen and not as a caricature,” he says, and the eighty honest images in salt & truth prove it.