I don’t typically shy away from garden work, but this year was different. Maybe the heat indexes were more oppressive—the stresses of the world certainly seemed so—or maybe I flat out did something terrible to make the soil more intent on feeding weeds than my tomatoes. When I’d look out over the raised beds from the window of my study in Columbia, South Carolina, I felt anything but the calm that scientific reports claim gardening brings. All I saw was a lengthening to-do list.

I needed a retreat from the ongoingness of writing projects, breaking news, and my misbehaving plants. A place where the mind has a chance to be still. I craved a visit to Pearl Fryar’s topiary garden, a three-acre expanse that’s been open to the public since the late 1980s. One might picture a beautiful but strictly geometric maze at one of the United Kingdom’s great country houses—such as Drummond Castle in Perthshire, Scotland, lined with formal clipped yews and boxwood hedges. This isn’t exactly what one finds at Fryar’s place in Bishopville, South Carolina.

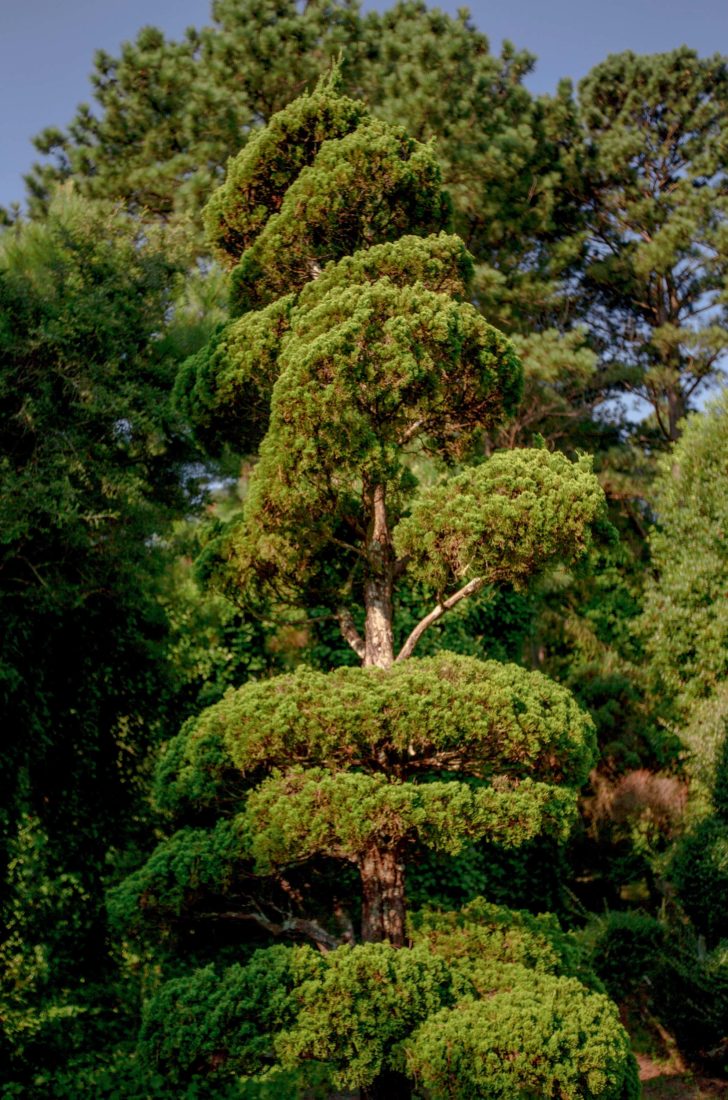

His garden lies just outside the seat of Lee County, known for its cotton production well into the twentieth century, where winding back roads reveal modest brick ranch homes. Down a peaceful, rolling street that ends in a cul-de-sac, Fryar tends a garden of topiaries that tower and turn. Evergreen trees and shrubs spread across the property in billowing abstract forms. Pines, junipers, and cypresses loom like sentries engaged in a slow, turning dance—some twisting in place, others bending and curving over wooden benches, fountains, and scrap-metal-and-bottle sculptures.

Fryar himself is an image of the kind of juxtaposition of unhurried affability and industriousness that I saw in the group of older Black men—caretakers and their friends on lunch breaks—at the horse farm my parents owned when I was a teenager. They’d stand around the wash stall and talk straight with each other about everything from truck repair to rural Lower Richland County’s latest gossip. Fryar also knows how to shoot the breeze, and he treats everyone the same in doing so, but beneath that relaxed demeanor is a determination to be the best at his work. As I was growing up, my parents (like most of their generation) told me that as a Black girl, I needed to work twice as hard to prove myself in life. I often struggle with the idea of living up to this as a writer, but the self-taught topiary artist’s garden is a testament to that mindset of overperforming in order to be accepted.

When I took a break from my own garden to see Fryar’s this past summer, the eighty-year-old had been ill and unable to carry out his regular pruning work. A caretaker was providing maintenance as the garden remained open to the public, but shrubs that had once been clipped into curves were starting to grow green outside the lines. As if the garden were a devoted pet, it refused to completely bend to the will of a substitute while it waited for its human to return and care for it.

I first heard of Fryar’s garden about a decade ago and continued to learn about the man through mutual friends and my time on the board of the South Carolina Arts Foundation. The foundation works with the Arts Commission to grant Elizabeth O’Neill Verner awards—the state’s highest arts honor, which Fryar received in 2013. The son of a sharecropper, he grew up in the small town of Clinton, North Carolina. He started college but had to leave when he was drafted for the Korean War. Once he’d served his country, he landed in New York, where he worked for a canning company that eventually transferred him to Lee County. When he saw a house he wanted to purchase in Bishopville, he was told he couldn’t because he wouldn’t “keep it up.” It didn’t matter that he was a financially savvy and steadily employed individual who could afford the place he wanted. The assumption was that a Black man wouldn’t have the pride or standards to keep his property in an acceptable state for people passing by. So he found a piece of land just outside of town, built his own home, and made the three surrounding acres his creative domain. In 1981, he decided that he wanted to win Yard of the Month. It turned out he wasn’t eligible because of his house’s location—another rub to spur him on. He went to a nursery in the neighboring county and spent just minutes getting tips on how to create a topiary. That was enough to light the match of his creativity, fueled for longevity by pride and ambition. For nearly forty years, Fryar has used chain saws and hedge trimmers to lovingly train natural materials into obedience, and his garden draws visitors from around the world.

When I again walked the grounds, the gentle curves of the sculptured greenery pressed over the noise of my life. I had no tomato blight to worry over and no quarantine quarrels to sort out for my children, and I remembered that my own relationship with a garden’s stubborn wildness, with the cycles of life, requires give and take and quiet love. Here grew the living proof of one man’s grit and vision—traits that carry us through decades of ups and downs, triumphs and pain.