On May 23, more than 82 years ago, the outlaw duo known as Bonnie and Clyde were shot to death in a police ambush as they drove a stolen Ford along a rural road in northern Louisiana. It was a stunning end to a stunning spree of crime.

Both Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow were born in Texas. After meeting and falling in love in 1930, the two commenced a violent tour throughout Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and as far north as Minnesota from 1932 to 1934. Their string of bank heists, gas station robberies, shootouts, and a jailbreak left at least nine police officers and a handful of civilians dead. Since their deaths and especially since the 1967 film, Bonnie and Clyde, starring Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty, popular culture has glamourized the murderous pair and even villainized the Texas lawman, Frank Hamer, who tracked them down.

A promotional photo from the 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde.

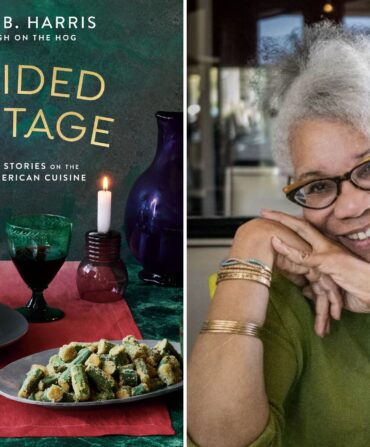

For his book, Texas Ranger: The Epic Life of Frank Hamer, The Man Who Killed Bonnie & Clyde, John Boessenecker, a historian who has written eight books on the Old West, former police officer, and now trial lawyer, spent five years poring through FBI files, books, and hundreds of news reports to set the record straight on Bonnie Parker, Clyde Barrow, and Frank Hamer, the man he calls “the greatest lawman of the twentieth century.”

Bonnie was no “girl-next-door” and Clyde was no misjudged youth.

“Bonnie and Clyde were punks who robbed gas stations, and were nearly forgotten until the film made them famous characters,” Boessenecker says. “The myth became that they were a misunderstood young couple ruthlessly gunned down, and that’s just not true. They were sociopathic killers. None of the facts support the myth that Bonnie was a Faye Dunaway.”

Photo: Courtesy Taronda Schulz collection

A photo of Bonnie discovered after a gunfight in Joplin, Missouri.

Boessenecker’s research confirmed that both Bonnie and Clyde murdered and injured more than a dozen people throughout the South and Midwest, both had guns in their hands when they died, and the shot-up Ford was an “arsenal on wheels.”

Photo: Courtesy Taronda Schulz collection

The pair’s “death car” and firearms at the scene in Louisiana shortly after the ambush.

Frank Hamer was not a bloodthirsty killer hungry for redemption.

“The film made Hamer out as the villain who wanted to ambush them in revenge,” Boessenecker says. “The film’s character was really a composite of several officers who had been kidnapped by Bonnie and Clyde. Before the actual ambush, Hamer had never been in close proximity to the two.” When the state of Texas hired forty-nine-year-old Hamer to track down Bonnie and Clyde, he was a former Texas Ranger who had seen everything from the Old West’s horseback days to the 1930’s gangster era.

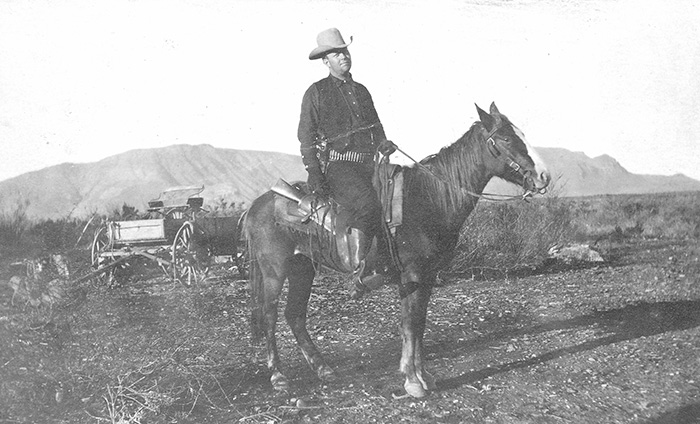

Photo: Courtesy Travis Hamer personal collection

Frank Hamer in about 1910.

Frank Hamer in about 1910. (Photograph courtesy Travis Hamer personal collection)

Hamer worked with multiple law enforcement agencies throughout the South to study the pair’s habits, including as he described later, “the kind of whiskey they drank, what they ate, and the color, size, and texture of their clothes.” Hamer’s sleuthing was the calculated work of a skilled law agent, argues Boessenecker: “Hamer traced Bonnie and Clyde to Louisiana by methodical investigation.”

Photo: Courtesy Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum

Hamer on his horse Bugler, during the Bandit War of 1915.

It might be time for a film remake.

One of Boessenecker’s primary sources was discovered in a Dallas courthouse in 2008—an FBI file stuffed with more than 500 pages of original reports, articles, photographs, and correspondence. Boessenecker spent dozens of hours combing through the details and visiting courthouses throughout Texas for follow-ups. Many researchers have examined the FBI file, but few have focused on the man who brought down Bonne and Clyde. “He exemplifies the transition from ranger on horseback to modern law enforcement,” Boessenecker says. “Frank Hamer really did lead an epic life.”