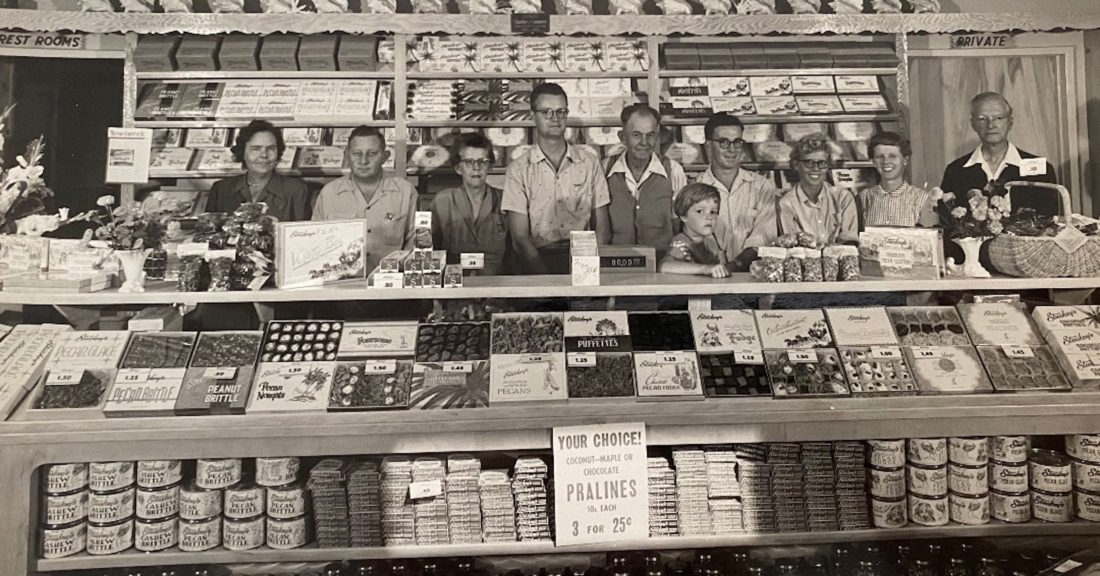

For pilgrims of a certain age, no road trip through the South was complete without a break at a Stuckey’s, the shop and gas station beloved for its signature Pecan Log Rolls. W.S. “Sylvester” Stuckey Sr. had started the business in 1937 with a modest “nut hut” on the side of the road in Eastman, Georgia, a pit stop that proved irresistible to snowbirds traveling to Florida. By the 1950s and 1960s, Stuckey’s had become an Americana empire with more than 350 stores in thirty states. In the 1970s, though, a corporation bought out the company, and its popularity declined.

A turnaround started in the mid-eighties, when Stuckey’s son, W.S. “Billy” Stuckey Jr., bought the brand back, but when his daughter Stephanie—an Atlanta attorney, longtime Georgia representative, and environmentalist—took over as CEO in 2019, she put her savings into the company and the pedal to the metal. In her family’s filing cabinets, she discovered priceless accounts and photos of the Stuckey’s of yore, and building on that nostalgia, set out to revive the Stuckey’s so many knew and loved—a move that included buying a candy factory in Wrens, Georgia, to produce their signature sweets and other snacks once more for the sixty-five franchised locations that remain.

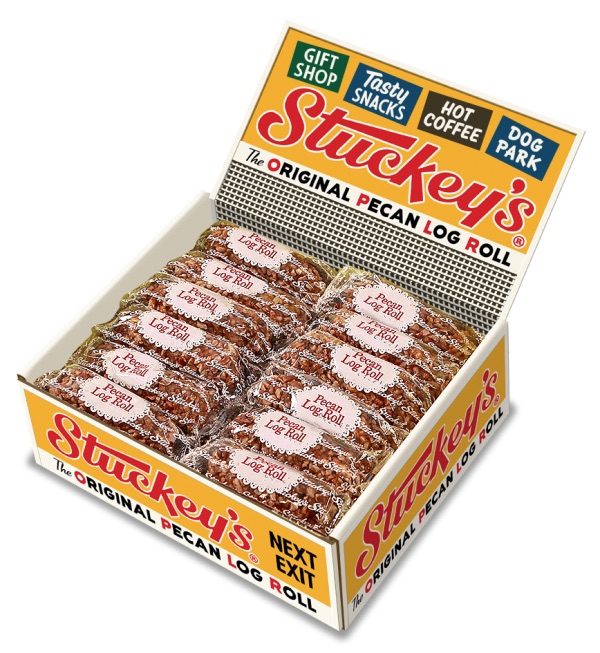

Now you can often find Stephanie Stuckey on the road, touring the region and stopping at Stuckey’s herself to promote the iconic Southern stop as a place to pause—along with that Pecan Roll delicacy, with its crunch and creaminess in the same bite. “Our secret sauce is that we’re a family brand that has an eighty-plus-year history of churning out delicious candies,” she says. “I’m totally owning that nostalgia as part of our DNA.”

Here she shares more about what it’s meant to step into the family business.

First, can you settle that age-old debate among Southerners about pronunciation: “pe-cahn” or “pe-can”?

As you can imagine, I get asked this question a lot! In the South especially, folks have very strong feelings about our region’s native nut. The pecan is really personal to us because so many of us grew up with pecan trees in our yard, cracking them on the porch with the family and swapping stories. So, how you say it is not just a matter of pronunciation, it says a lot about where you come from. I’m from Middle Georgia, and I grew up saying “pee-can,” which gets a lot of jokes about “isn’t that what rednecks keep in their outhouses?” But I’m going to embrace my Southern drawl and red clay roots on this one. It’s pee-can.

The origin story of the Pecan Log Roll calls to mind Horatio Alger in seersucker.

I love that, although in this case it’s a Horacina Alger story, since my grandmother is the one who came up with the recipe for our classic Southern confection. I like to say that while Ethel Stuckey didn’t invent the Pecan Log Roll, she certainly perfected it. As the story goes, my grandfather started Stuckey’s with a $35 loan from his grandmother, driving a Model A Ford around the countryside in Dodge County, Georgia, with a Black man named Joe King, who worked on his family farm. The two of them would buy up pecans from local farmers, and my grandfather would sell them at a little roadside stand on Route 23.

He got inspired one day to add pecan candies to drum up sales, and ran the mile to his home to recruit my grandmother, Ethel, in this new endeavor. She was playing bridge with her friends, but those ladies stopped their game to go help in the kitchen. None of them knew what they were doing, but they figured it out using some old family recipes. Together, they perfected methods for making divinity, pralines, and fudge—those candies came first. And later, Ethel repurposed a family recipe she had for pecan log rolls to include bits of maraschino cherries, and came up with her secret method for getting the nougat to harden just the right amount.

What I love is that those bridge ladies continued for years making Stuckey’s candies until my grandfather built a candy plant. That bridge club turned candy club included some of my aunts and a close family friend named Sylvia Rubin, one of the few Jewish residents of Eastman, Georgia, at the time. I love that Stuckey’s origins include the contributions of a Black man, a Jewish woman, and my own grandmother, who was active in the Stuckey’s business, both in the kitchen and the boardroom. A lot of white businesses founded in that era had the support of minorities and women that have never been given credit. I think it’s important to acknowledge that as I move forward with rebuilding the brand.

How did Stuckey’s become such a staple of the American road trip?

Stuckey’s was really the first roadside retail chain. Looking back on it, what my grandfather did was really quite revolutionary. There were no consistent, reliable places to stop to get gas, fill up with a hot snack, grab an ice-cold drink, and use a clean restroom until he came along. In the early 1940s, when he started building brick-and-mortar stores, there were no Pilots, TravelCenters of America, Love’s, or any of the other chains that populate interstate exits today. In fact, Stuckey’s even pre-dated the interstate! So being the first of its kind really made a difference.

And we also were part of the whole road trip experience. Stuckey’s hit our stride when family vacations meant hitting the road crammed in a woodie station wagon, staying at HoJo’s, and visiting Disney World. We were part of that wonderful era of playing license plate bingo, fighting with your siblings, talking to truckers on CB radios, and singing “Seasons in the Sun” endlessly from the back seat. When you pulled over at a Stuckey’s, you could expect something fun—we had talking myna birds; an incredible array of fun souvenirs, like the dunking birds and Mexican jumping beans; coconut spreads; and, of course, our wide selection of branded pecans and candies.

While a lot of this is now in the past, we see people rediscovering the road trip in new and different ways, especially post-COVID. Despite falling out of family ownership and a series of corporate takeovers, Stuckey’s has managed to survive. I think that’s appealing to people, that gritty, we’re-still-standing perseverance that we embody. Like the road trip, we’ve had our ups and downs, but we’re dusting ourselves off, rebranding, and ready for a comeback.

What lead to Stuckey’s decline in the late 1970s? Did the interstate highway system play a role?

Actually, the interstate highway system played a role in our growth. It was a pivotal moment of resilience for my grandfather, as he had to make a choice about whether to struggle with his stores on the state routes that had been bypassed or close those stores and build new ones on the interstate. He opted for the latter and used it as an opportunity to rebrand our stores with that classic teal sloped roof design that became instantly recognizable as a Stuckey’s. Our decline is mostly due to my grandfather selling the company—he was getting older and ready to cash out. It was a good deal at the time, and he made a nice profit. But the corporate owners were more interested in building a profit instead of a brand. You often see that happen with nostalgic brands: They fall out of the hands of the visionary founder and lose their magic.

You’ve really boosted Stuckey’s online sales. Does the Pecan Log taste just as good if it comes from a website, or must you be road-weary on a cross-country odyssey to get the full experience?

I think our Pecan Log Rolls taste better now that we’re making the candy in-house again. For decades, our product was outsourced, and the quality suffered. The Pecan Log Rolls we’re churning out at our candy plant live up to the Stuckey’s name, using only the freshest Georgia pecans, and much of the process is being done by hand. You can truly taste the difference when candy is made by hand instead of a machine. That taste difference to me is what will invoke the feeling of being on a road trip, whether you buy your Pecan Log Roll online, in a Stuckey’s off the interstate, or at your local grocery store.

You spent more than ten years in the Georgia House of Representatives, and you recently persuaded lawmakers to name the pecan Georgia’s official nut. How does the peanut feel about this?

There’s a backstory to this. I read where Alabama had the pecan as its official state nut, and I was joking with a former colleague about how she should introduce a bill to make the pecan Georgia’s nut, since our home state has been the top pecan producer for decades. She encouraged me to do it, joking that it’s one bill that could guarantee bipartisan support during an otherwise contentious legislative session. So I put together a draft and had it introduced. But what’s great about this effort is that we got so many wonderful allies who really get the credit for passing the bill, like the Georgia Pecan Commission, the Georgia Grown program of the Georgia Department of Agriculture, and the Georgia Farm Bureau. It’s really about economic development: We want people to support our Georgia pecan farmers and know that our pecans are the most buttery and delicious nuts you’ll find anywhere in the world. And as for the peanut farmers—their trade association officially endorsed our effort because, as any farmer knows, peanuts are a legume and not a nut.