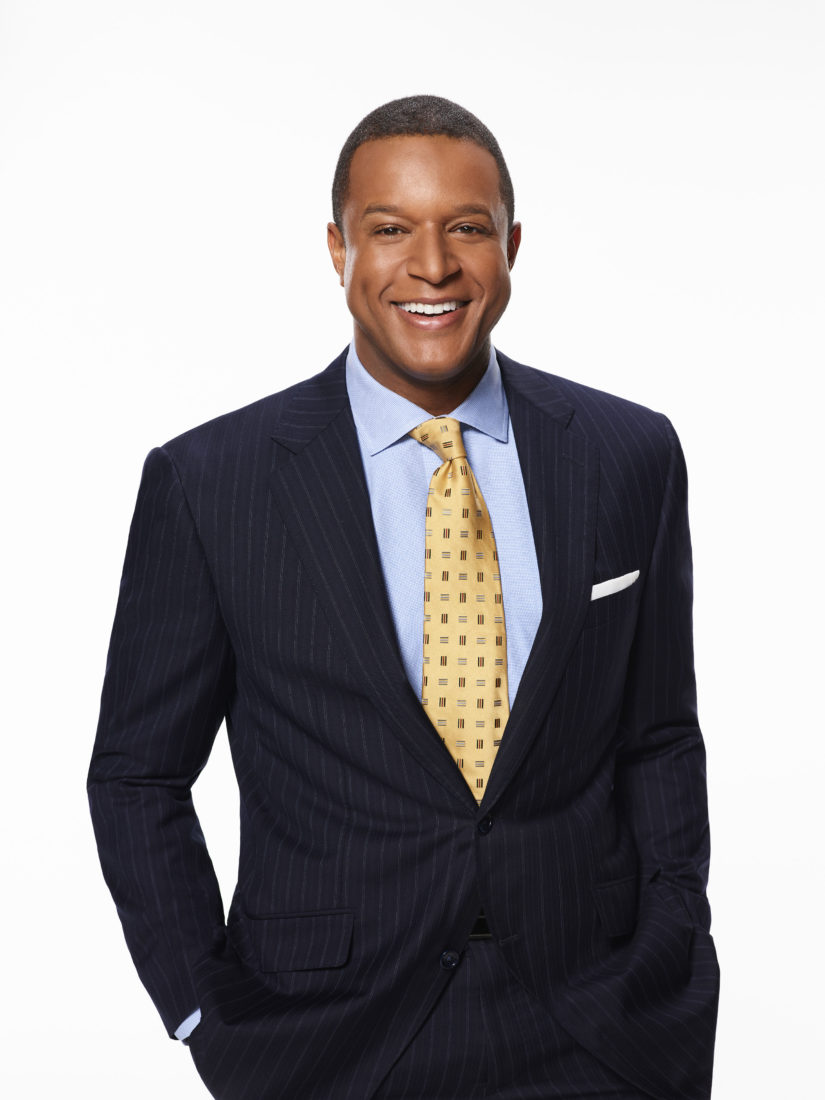

The broadcast journalist and Today news anchor Craig Melvin headlines a series on the show called “Dads Got This!,” which celebrates men who go the extra mile for their children and impact their communities. But for years he was reluctant to talk about his relationship with his own then-estranged father, who at times struggled with gambling and alcohol addiction.

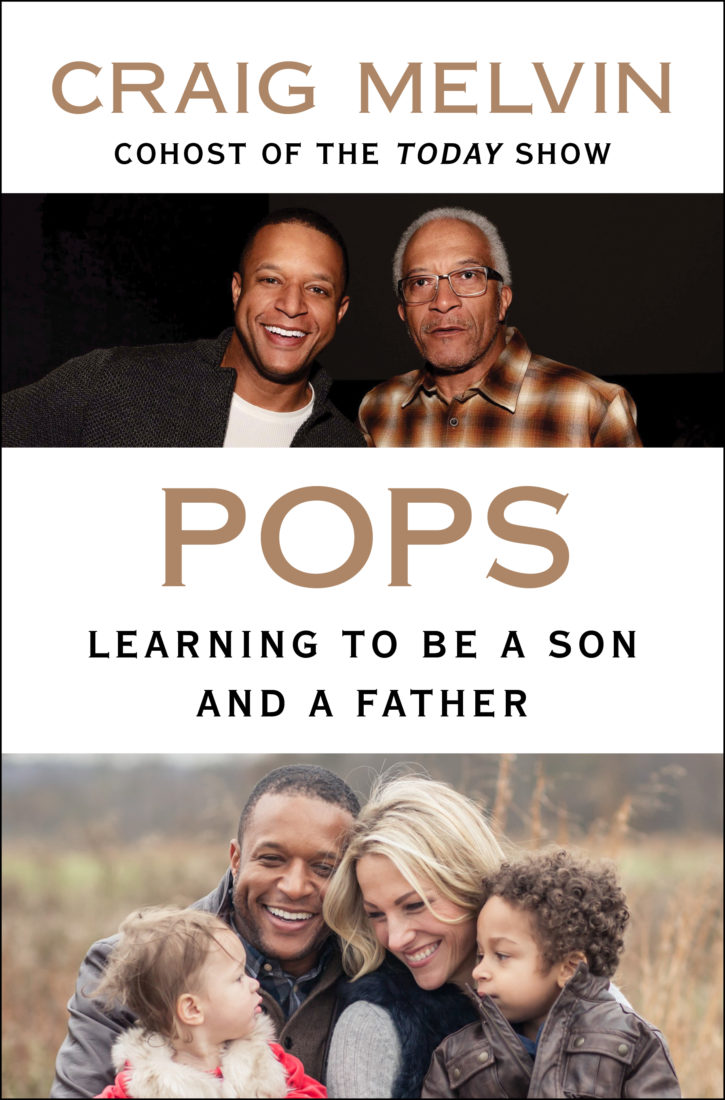

Melvin’s newly released book, Pops: Learning to Be a Son and a Father, takes readers back to his old stomping grounds in and around Columbia, South Carolina, to explore his family’s legacy of addiction, the choices his father made to survive, and how the gulf between the two men shaped Melvin’s idea of fatherhood and who he wanted to be when he started a family with his wife, Lindsay Czarniak, and became a dad to his two children, Delano and Sybil.

Here Melvin shares more about his upbringing and how he started asking his parents the hard questions.

You began writing this book at the very beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic—an incredibly fraught time. So many people started taking a full accounting of their lives, because we were thinking about the relationships we could lose due to isolation or illness. It seems you started doing that type of personal investigative digging into your background, too.

I started the book in February 2020. In the early stages of the pandemic, there was just so much we didn’t know. We were facing this existential threat as a society, and here I am having these extended conversations with my father and my mother. In the afternoons and evenings, I’m having these gut-wrenching exchanges about my life and my dad’s life and how we got here. One of the reasons I wrote Pops was to encourage people who look like us to have these difficult kinds of conversations with their families. There’s so much that we don’t talk about—medical histories, family secrets in general, our emotions—all that stuff. I know it isn’t easy.

Your dad is old school—in the book you mention he doesn’t carry a debit or credit card, and while he now has a cell phone, he doesn’t text. Times change, but often the advice that dads give us still rings true. Is there a piece of advice your father gave you years ago that still holds up?

He used to say when we were growing up, “If you can’t manage a house or car, if you can’t pay for it in cash, you don’t need it.” And I live by that to this day. My wife can attest to the fact that I have clothes that I’ve owned since I lived in Columbia. I have ties that I still wear that I had when I lived in Rosewood, in Columbia. We’re moving now and we’re purging. Yesterday, I wrestled with getting rid of this Polo Ralph Lauren suit. I remember the suit vividly because I bought it from Lourie’s on Main Street, in Columbia. This was back when men wore pleats and had cuffs in their pants. In my mind it was a major purchase back then.

This career in media, covering the biggest headlines of the day—it often takes a great deal of sacrifice to get to this point. What do you wish people better understood about you—about this job?

I made a lot of sacrifices in my twenties, and in my early thirties. I worked terrible shifts. I worked holidays. When you’re a young journalist, in our line of work at least, you’re working Thanksgiving, you’re working Christmas. you’re working all the holidays. And then I move away, and I can’t go home and visit as often as I’d like. I was a bad friend for a long time—I couldn’t be as supportive as I wanted to. I just wasn’t there. I’m not complaining because we have been blessed beyond measure. I’m not just talking about money, I’m talking about experiences and this job that I have where I’m able to say, “Oh, wow, this is a cool story, it’s out in Seattle, let’s go.” I live the dream in terms of my professional career, but the sacrifices are mighty. I’m on a plane a lot. I’ll spend two, three weeks in Tokyo for the Olympics. Is it an awesome opportunity? Yeah, of course it is. But I have young children, and I’m away from them a lot.

In the book when you realize that you’re grappling with these opportunity costs, you start to look at your dad differently. You and your dad didn’t see eye-to-eye for a long time—his relationship with alcohol strained things as you got older. He also worked the graveyard shift at the post office, which meant he wasn’t often around for things like sporting events. You realized, looking back, your father had to decide: to finish college, or to immediately start making money for his family. He did the latter. In the middle of the book, when you become a parent, you’re working out how to spend time with you children, and you say, “at some point you realize every father is sacrificing something.”

Right. Everyone sacrifices something—often money, or time. When I realized that, I said, “You know what? I’m going to focus on quality over quantity.” I made peace with the fact I’m not going to be at every soccer game or every Little League game. But when I am there, I’m there. The phone’s in my pocket, and I’m the loudest screamer on the sidelines.

In Pops you have a section where you discuss reconciliation and forgiveness. It starts off with a conversation the two of you had about the murder of George Floyd, and unfolds into a conversation about the Charleston church shooting and the very different reactions people had—about forgiveness, and justice. How did you work towards forgiving your father?

It was faith—I think that if you profess to be a Christian and you are reluctant to forgive, then perhaps you should ask yourself what kind of Christian you are. Even when he was a drunkard, he would talk about forgiveness and hypocrisy. We live in a time, and certainly in a society, where it is so easy to just cancel someone. Someone says something or posts something, and all of a sudden, it’s like, “Oh, they’re dead to me.” We struggle to accept the fact that people make mistakes. We all at some point fall short, and who should decide who gets a second chance and who doesn’t? You read the book—my grandma got a second chance. She was a bootlegger, she was running numbers, she goes to prison. When she gets out, she commits her life to serving Jesus Christ, and becomes an usher at her church. That’s the Grandma that I knew. That’s who shaped and molded me. Had she not gotten a second chance, what would have happened to me?

How did you care for yourself emotionally while you were trying to figure all of this out?

In terms of self-care, I still struggle with it. I’m a firm believer in therapy and see a therapist on a regular basis. It’s funny because I’ve also become that guy that encourages other people, frequently unsolicited by the way, to see and talk to someone. We all need to, especially in this job, because if you’re doing it right, I think, the stories stay with you. That means I also need to find ways that I’m able to cope. I’ve discovered mindfulness and use the app Headspace. It’s been a lifesaver for me during the pandemic.

I also try to start the day with meditation or journaling. On Monday, I’ll meditate; Tuesday, I journal; Wednesday, I meditate. I do one of the two every morning and it has saved my soul. No doubt.

When did you learn your dad was proud of you? Has he ever said those words?

It’s been in the last year or two. One Monday afternoon he called to check in, and he made some reference to a segment that I had done on the show that day. And I said, “Pops, you’re watching the show?” He’s like, “What do you mean?” I was like, “You saw the segment?” And he’s like, “I watch every day.” I was like, “You mean you watch every day?” He’s like, “I watch the show every day.”

So a day or two later, I have a conversation with my mother, and I brought it up with her. She said, “Oh, well, he watches all your shows, even the Datelines that come on in the middle of the night. If he knows you’re going to be on, he’s watching. Sometimes he’ll scroll through the guide to see….” Part of his deal is, he doesn’t call every other day to tell me that he’s watching; I would not have even known that he was watching had I not asked him. It’s a quiet pride. This is who he is, or who he’s become.