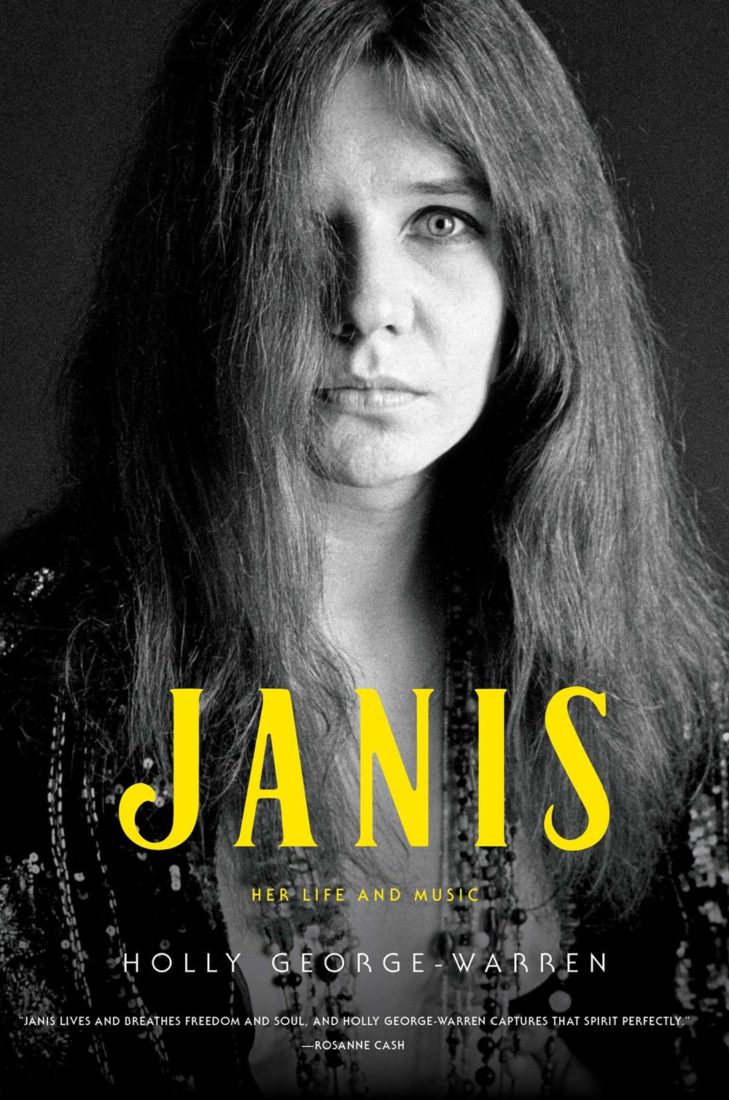

Janis Joplin’s home state of Texas was like a cruel lover—at times it would build her up and fill her soul with music. Other times, it tore her down and took another little piece of her heart. A fascinating, deeply researched, and powerfully written new biography, Janis: Her Life and Music by Holly George-Warren shares the story of one of rock-and-roll’s most unforgettable voices. Beginning with an exploration of how the Lone Star State shaped Joplin’s music and life, the book follows her eventual move to California, her shooting-star rise, and her death at age 27 in 1970.

“Janis always had an independent cowgirl spirit,” George-Warren says. “She had ancestors who helped build Fort Worth, and she was proud of her pioneer heritage. She was a tomboy and she had the courage to break away from women’s traditional roles in the deep South.”

Born on January 19, 1943 in Port Arthur, a Gulf Coast town near Texas’s border with Louisiana, Joplin first sang publicly in church as a young girl. Joplin’s mother wrote notes on the back of photographs, many of which George-Warren includes in the book. On one photo of Joplin as a child, her mother wrote how young Janis “sings herself to sleep.” On the back of a photo of Joplin visiting her grandparents in Amarillo, Texas, her mother noted that she said, “We are going home now. I’ll have to be good.”

Like many young women of her era, Joplin was seduced by the music of Elvis Presley. But she took her fascination a step further. After seeing his 1956 performance on the Ed Sullivan Show, she tracked down an original recording of “Hound Dog” by Big Mama Thornton. “How a thirteen-year-old white girl in segregated Port Arthur found the R&B single remains a mystery, but she did,” George-Warren writes. She became a student of Southern blues, and a devotee of Louisiana guitarist Leadbelly and the Tennessee-born “Empress of the Blues” Bessie Smith.

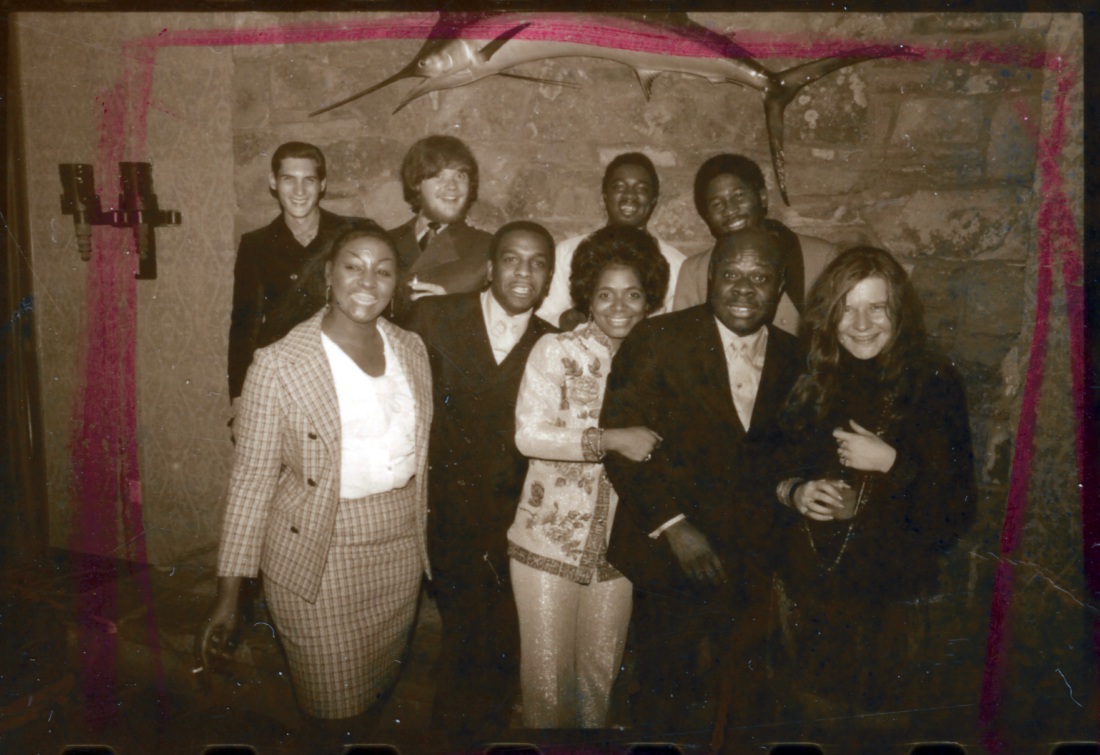

Joplin’s interests and burgeoning political beliefs as a high schooler put her at odds with her classmates—and the notion of being what George-Warren describes as a “genteel, proper middle-class daughter.” “During a classroom discussion on integration, Janis was the sole student to argue in favor of black and white students attending school together,” George-Warren writes. Her opinions “would eventually, by her senior year, cut her off from conventional Port Arthur.” She wore purple tights instead of the typical bobby socks, and then adopted a weekend uniform of Levi’s, an oversized men’s white shirt, and dirty white canvas shoes.

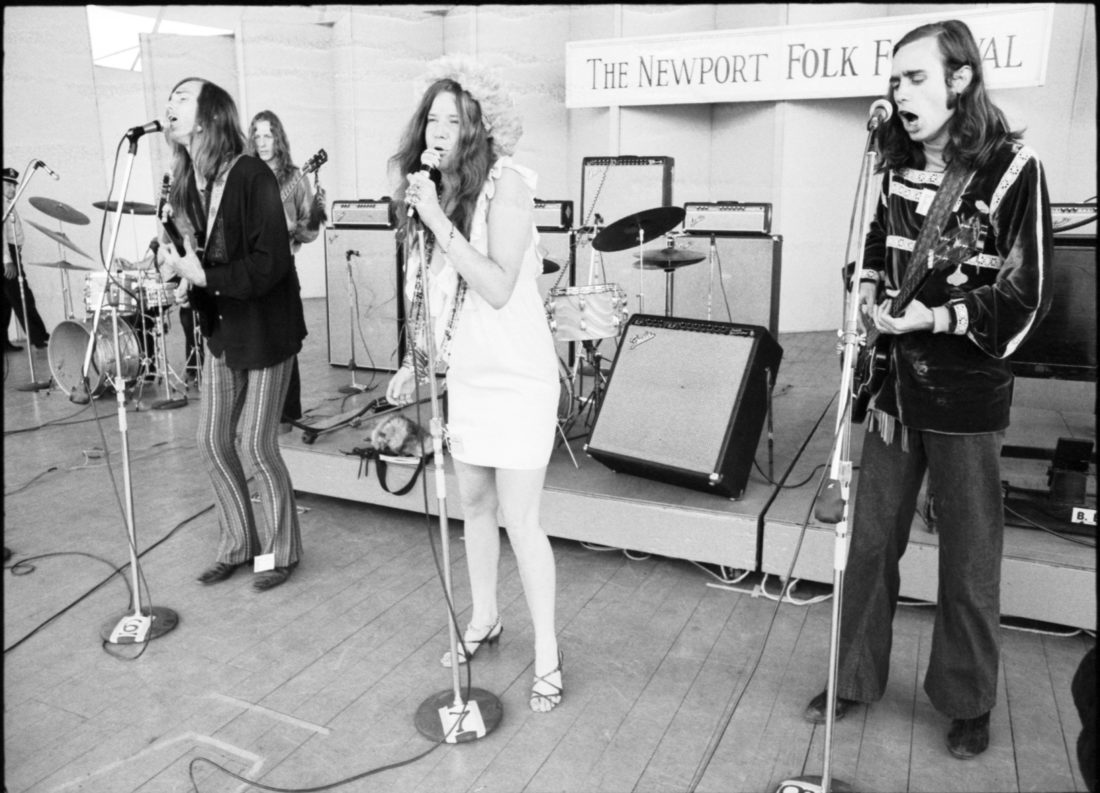

Her music career began to blossom in Austin, where she was enrolled at the University of Texas as an art major and started playing gigs with local band the Waller Creek Boys. “She discovered herself as a singer,” George-Warren writes, “gaining an audience, building her confidence, and holding sway as Austin’s most mesmerizing blues singer.” The city gave and it took. Joplin’s style, her bisexuality, and her bohemian persona were too much for some co-eds. Someone nominated her in the Alpha Phi Omega fraternity’s “Ugliest Man on Campus” contest, and it deeply wounded her. Joplin wrote in a 1965 letter, “Finally, I decided Texas wasn’t good enough for me.” She hitchhiked to San Francisco, where “she wanted to live like a beatnik and sing the blues.”

“I think that deep down, even though she was outspoken against the social norms of Texas, she still considered herself a Texan,” says George-Warren, whose book chronicles the rest of Joplin’s musical development, her travels, and her life in California. “I got to read all of her letters she would write home to her parents, and she was always conscious of Texas, asking if the Port Arthur newspaper was writing about her new record. She wanted to go back to Texas to perform and prove that she was a success.”

Last Saturday, George-Warren held a book signing at the Museum of the Gulf Coast in Port Arthur. “I had no idea what to expect, bringing this book to Janis’s hometown,” she says. “But the place was packed, Janis’s brother Michael Joplin joined me to sign books, and the line wrapped along the building and down the street. We signed books nonstop for three hours. The crowd was diverse, too. It was powerful. I couldn’t help but think Janis was smiling down.”