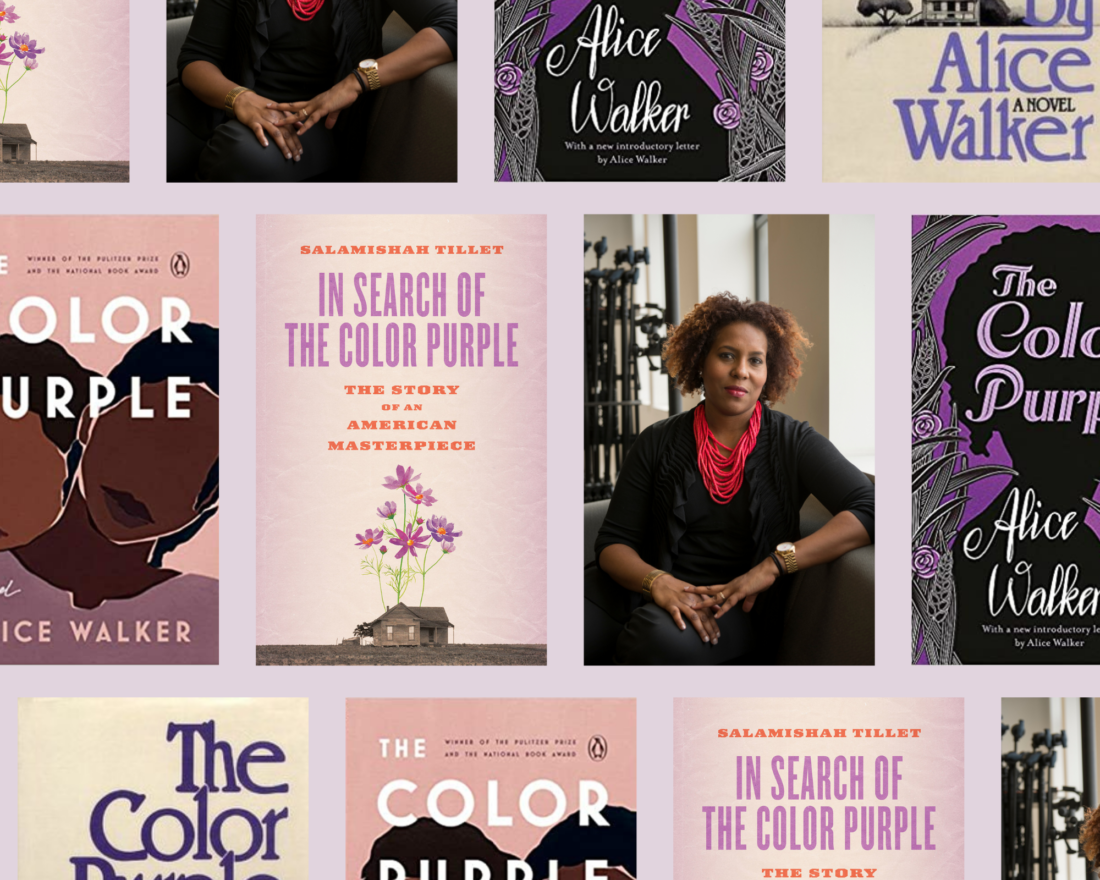

An essential entry in the encyclopedia of the Southern literary canon, Alice Walker’s 1982 novel The Color Purple spawned an Oscar-nominated movie, a Tony-winning musical, and, according to writer Salamishah Tillet, “changed the history of the novel.” The work, told from the point-of-view of Celie, a fourteen-year-old Black rape survivor growing up in Georgia under segregation at the turn of the twentieth century, would go on to win the National Book Award for Fiction, and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1983, making Walker the first Black woman to garner those recognitions.

But the novel’s influence didn’t stop there. In Salamishah Tillet’s latest work, In Search of The Color Purple: The Story of an American Masterpiece, Tillet delves into the backstory of the novel, explores why Walker’s book continues to resonate, and explains how the literary work became a cultural phenomenon, all while masterfully weaving together personal, cultural, and historical conversations about the text, including original interviews with Walker herself and players in the film and musical such as Oprah Winfrey, Quincy Jones, and Danny Glover.

Tillet, a contributing critic at large for The New York Times and the Henry Rutgers Professor of African American Studies and Creative Writing at Rutgers University, first read the story of Celie as a teenager, and the book has served as guidepost for her at various times in her life. Walker’s writings inspired Tillet’s own activism, moving her to cofound A Long Walk Home, a national nonprofit that uses art to empower young people to end violence against girls and women.

Here, Tillet shares more about her time with Walker and the writing process from her home in Newark, New Jersey, where she is hard at work on her next book, about the life of Nina Simone.

You first read Alice Walker’s The Color Purple thirty years ago. What has this novel meant to you over the years?

There is just so much about this book that’s radical—Alice Walker was able to center an entire novel in the African American Southern vernacular English, which had never happened before in the entire history of the novel. She invited people into the world of a Black girl from the South in a way that allowed them to see themselves and others—that’s revolutionary, and a way to engage in such a radical act of empathy.

In the opening of your book, you talk about visiting Alice Walker and watching her observe nature. What did that reveal to you about Walker’s relationship with her environment?

I understood Celie’s arc more by being in Alice Walker’s presence in Philo, California. She lives atop forty acres of land. Sitting in her company gave me such deep insight into her level of empathy. Alice Walker is someone who tried to channel the voices of those who are typically rendered invisible. She has such a compassionate energy about the lives of everything and everyone around her. Seeing that, I think, gave me a deeper appreciation of Celie’s own arc.

I also went to her hometown of Eatonton, and this is where I was the most surprised, because the town is utterly gorgeous. Not only was it the setting of The Color Purple, but I recognized that in this book she was trying to balance this deep appreciation for nature as this gift from God, and understand these human courses of oppression, like sexism and racism. That’s what disrupts the safety and the beauty of the natural world—these institutions in which someone like Celie can be so easily discarded and easily just rendered a victim.

After being in conversation with Walker and her writing, how has your understanding of nature and the environment changed?

I went to Eatonton first, and then went to Alice’s current home in Northern California—then finally, back to Eatonton. Afterward, I understood how important it was that she be surrounded by beauty for these characters to be born.

I’m from Boston and New Jersey, and I lived in Trinidad, so I didn’t grow up in the South the way that Alice did. I didn’t grow up with the land the way Alice did. I think in my early years I misread the book. I think I saw the novel’s setting as such a restrictive violent place in which both the physical home, but also the state or the town, was violent. I think there is an ongoing misreading of the South on the part of many Black people who live in the North. We hear the trauma, but we don’t see the beauty that it exists in contention with.

When I went to visit the place where Alice Walker was born, the land on which she was formed, there was this gorgeous tree and I was like, Of course, this is what she was trying to do. She was trying to show us not just the beauty of Celie and the community that she was able to nurture—she was trying to get us to see the divine in all aspects of the South.

As a critic of culture, you’ve got an interesting perspective on public reaction. The Color Purple resonated with many people, but it was also, as you’ve documented, criticized. Are there other works of art that strike you as being similarly received?

The Color Purple is unique because it got recognized by the literary establishment, but also got critiques and celebration from Black people. I think Beyonce’s visual album Lemonade is similar to a certain degree. It’s a work of art that Black women cherish and critique, but then she doesn’t get the Grammy for Album of the Year. I think she took that to heart as a rejection of a particular story that she was telling. In that moment we were seeing an artist at the height of both her political insight and her artistic vision. You don’t get those moments that often. When we do, we’re lucky to be on Earth when those pieces of art come into being. I’m so interested in Black women from the South, because I think there’s something deeply expansive about their world view.

The ideas of forgiveness and redemption intertwine in Walker’s book as well as your own. What do you take away from your journey on forgiveness, and the journey of forgiveness that Celie goes on in The Color Purple?

I think in the early years of dealing with my sexual assault, I blamed myself, like so many victims of sexual violence do. It was important for me to learn to forgive myself as part of my healing process, because I had to learn how to trust myself, and then by doing so, learn to trust others.

Debates about forgiveness are often given without discussing atonement. So, what does it mean to ask people to forgive without asking people to atone? What I got from The Color Purple—which I still think is so ahead of its time and is such a radical gift—is that Alice Walker gives us this character of Albert, who goes through the whole arc of making amends, seeking redemption, and wanting to reconcile, because he understands he’s harmed people. He’s not the hero of the book, but he is such an amazing character to hold and to witness. I think that he is someone who instructs us on what atonement looks like, and what our standard, in many ways, should be.