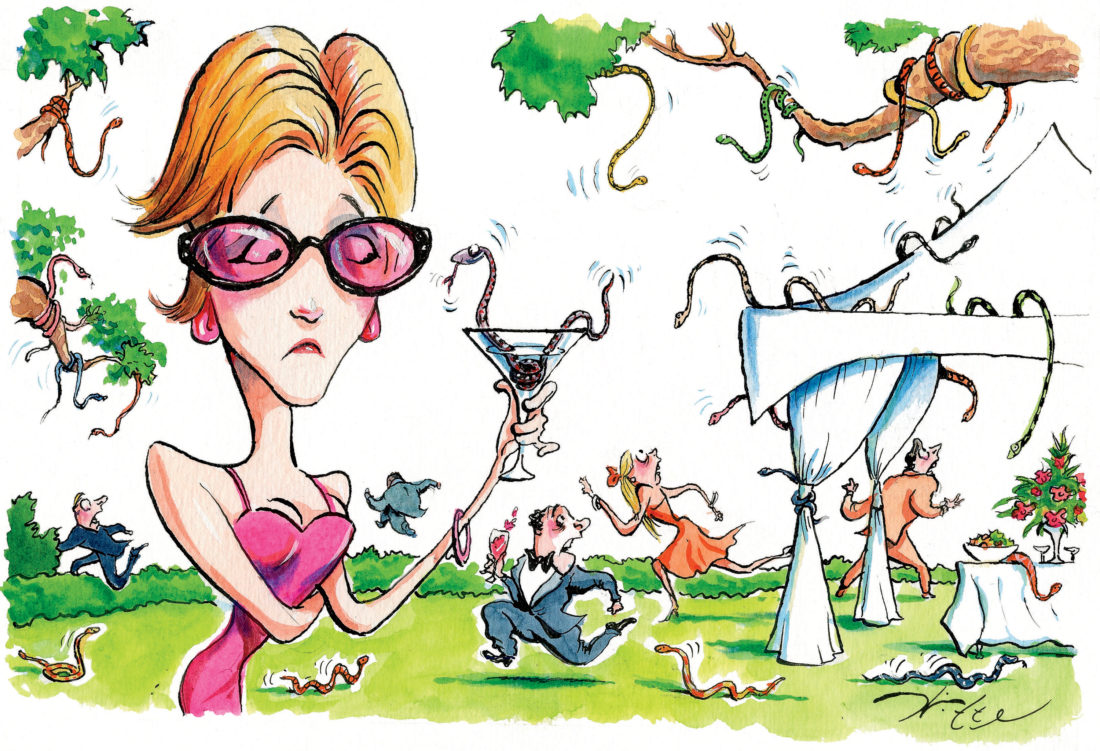

When I got married in my Mississippi hometown, I wanted to ensure that the guests, many of whom were not from the South—or even America—understood where exactly it was that they were visiting. To that end, there was a dinner at Doe’s Eat Place and another in an abandoned cotton gin. There were blues bands and soul bands and a festive pre-wedding lunch featuring pimento cheese sandwiches, ham biscuits, and fried chicken. Everybody went home with warm memories of my home state in particular and the South in general, and it wasn’t until I got the pictures back that I realized I had given them even more local color than I’d thought.

It was a group shot from the lunch. People were gathered near the bar on the terrace, sipping Bloody Marys and laughing away, while beyond them a bank of French doors led inside to the feast. Maybe it was because the cypress doors were stained a dull brown; maybe it was the booze and the bonhomie. Either way, not a single guest noticed the six-foot-plus-long chicken snake coiled against one of the open doors.

I grew up in the middle of what is most often called simply “the Delta,” the region in the northwest corner of the state which is in actuality the seven-thousand-square-mile diamond-shaped floodplain between the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers. Described by one early traveler as a “seething lush hell,” it was, until well into the nineteenth century, the almost exclusive domain of panthers and bears, wild hogs and deer, alligators and, of course, snakes. Lured by the agricultural possibilities of some of the richest alluvial soil in the world, a handful of white settlers finally turned up in the 1820s and began hacking out fields and plantations from what Faulkner called “one jungle one brake one impassable density of brier and cane and vine interlocking the soar of gum and cypress and hickory and pinoak and ash.”

Faulkner and his alter ego Ike McCaslin did not much approve of this process, but they may well get the last laugh. Like the bad child you can’t turn your back on, “not even for one minute,” all that vanquished wilderness keeps finding ways to fill up its old space, aided by a subtropical climate and an average of sixty inches of rainfall a year. The Delta’s oak-hickory forest is, after all, at least sixteen thousand years old, and snakes are a whole lot older.

Depending on the source, Mississippi has up to fifty-five species of snakes, including nine venomous ones. (By comparison, Maine has one venomous snake, and it’s found only in the southern part of the state.) I saw my first rattlesnake at four, when I almost stepped on it, running from our swimming pool to our house. At roughly the same age, my little brothers thought it adorable to bring home the baby water moccasins they found in the aptly named Rattlesnake Bayou, the nearby muddy stream that gave its name to the country road we lived on and that used to drain the whole town. Just last year, my best friend, Jessica Brent, was taking a bath when what she hopes was a harmless king snake (she never found it) took a peek at her from a stack of towels in the open linen closet.

Not that Louisiana, where I live now, is much different. Roughly 450 venomous snakebites are reported annually, and after each one of the state’s many floods, the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries finds it necessary to remind residents to “seal gaps in windows and doors” and protect their “feet, ankles, and lower legs” against displaced snakes in general, and cottonmouths, copperheads, and canebrake rattlers in particular. Here, too, there’s a bayou named after a snake, the lordly Teche, derived from a Chitimacha word. According to Chitimacha legend, a giant snake attacked their villages, required a bunch of warriors to kill it, and left its carcass behind to decompose and fill with water. In commemoration, the city fathers of Breaux Bridge commissioned a twenty-foot granite snake sculpture that resides in its downtown park.

Morgan City, where the Teche empties into the Atchafalaya River, also pays tribute to the snake, but in the form of an unlikely event called the Snake Bite Triathlon, a swim, bike, and run through what the organizers refer to as the area’s “beautiful swamp.” Unbelievably, they also tout the “cypress trees, cool lake, and lots of snakes” that mark the location, but when I drove through Morgan City this past summer, it wasn’t a snake that got my attention. It was an alligator who had eased up onto Highway 90 and lost his head to the wheel of an oncoming car—a common sight down here in what we should only laughingly call civilization.

It has been nine years since my Mississippi wedding, but apparently the snakes continue to hang around the doorsteps. The last time I was home, my mother shrieked at me to “shut the door!” using additional language she reserves for dire occasions. For a refreshing change, the mosquitoes weren’t swarming, so I was confused. “It’s not the mosquitoes,” she said. “It’s the snakes.” Snakes? Okay, then, best to keep the door shut. There’s a reason Mississippi State University’s Extension Service has issued a downloadable pamphlet called “Reducing Snake Problems Around Homes.”

The pamphlet makes the point that chemicals and fumigants have never effectively repelled snakes, and that home remedies concocted to keep rat snakes (the proper name of the chicken snake that attended my wedding lunch) at bay also have proved fruitless. These range from cayenne pepper spray to artificial skunk scent, but at our house we’ve always gone straight for the hoe. It is usually wielded by Frank Liger, the man in charge of my parents’ house, garden, and pretty much every other aspect of their lives, but he is often forced to employ a helper to stay on top of the reptile situation. Frank reckons that hundreds of snakes reside in our six-acre yard and says that even when he is not actively looking for them, he runs into one or two a day.

The morning after my mother’s meltdown, I found Frank and his helper with three black racers they’d cornered in a clump of bamboo. This is not easy to do. Described as curious (they will raise their heads out of the grass to check out what’s going on) and extremely quick (Frank calls them road runners), they also eat stuff like rats and even other snakes. But Frank was not interested in their more helpful qualities, he was interested in keeping them out of the house. “When I see one,” he said, “I try to do him as quick as I can.” What about king snakes? I asked. Their diet actually includes racers, and unlike their prey, they don’t often strike. “I don’t trust them either,” he said. “A snake is a snake. I’m not fooling with anything crawling on their stomachs. I know they are the devil.”

Which brings us to another point: the resurgence in snake handling in certain Pentecostal churches. In May, a preacher named Mark Wolford died of a bite inflicted by a yellow timber rattlesnake during a service in West Virginia. Though his father had died the same way twenty-nine years earlier, and he himself had barely survived at least four bites from copperheads, he remained undeterred, believing that if you die, it simply means it’s your time to go. It also means that you provoked the hell out of a normally skittish snake—copperheads in particular will try hard, according to my snake book, to avoid confrontation. Prior to the fatal attack, Wolford had passed the rattler around to members of his congregation; when he sat down on the ground next to it, the snake put an end to the proceedings by biting him on the thigh.

At this point, I have to say that I’m sort of with the snake. According to my buddy Rob Ballinger, a biologist with the Mississippi Fish and Wildlife Foundation, 75 percent of all bites from venomous snakes occur when someone is trying to kill or harass them. Being passed around to people shouting, speaking in tongues, and jumping up and down in time to tambourines must surely qualify as the latter. Still, the preachers persist. Less than two months after attending Wolford’s funeral, Andrew Hamblin, the twenty-one-year-old pastor at the Tabernacle Church of God in LaFollette, Tennessee, asked his county’s commissioners to repeal a state law prohibiting the ownership of venomous snakes. The commissioners quashed the resolution, and the law, enacted in 1947 after snakebites killed five people in churches during a two-year period, still stands.

Hamblin, who has been bitten four times, ignored the vote, posted news of an upcoming service on Facebook, and allowed a news crew to film it. Before the service began, a church member pulled three copperheads out of a wooden box, swung them over his head, and handed them to Hamblin, who raised his free hand in prayer. “My main thing is to see lost people saved,” he said, “but I would love to do it under the anointment of God with two rattlers in my hand.”

All this stuff goes back to a little-known passage in the Gospel of Mark, which reads in part, “They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them.” I’m no theologian, but I’m not sure that’s the first passage referring to snakes I’d zero in on. For one thing, most biblical historians say the passage wasn’t even in the first Greek versions of Mark. More important, the serpent was identified as the guy you want to seriously avoid pretty much from the get-go. In case anyone needs reminding, my aforementioned friend Jessica and her two sisters, Eden and Bronwynne (aka the Brent Sisters), recently released an excellent CD of their mother Carole’s songs, one of which contains the following instructive lyrics: “Adam and Eve had a real nice pad in a kingdom by the sea. / Along came a snake, a rake on the take, and the landlord demanded the key.”

Temptation, as we know, strikes everyone, even in this seemingly off-putting area. A roundup of recent deadly snakebites in our region includes one in Chattanooga that occurred when the victim was trying to determine a copperhead’s sex and another in Putnam County, Florida, when a fire marshal reached for a rattler who sought refuge under a shed after his neighbor shot at it. I am fairly sure I don’t know anybody that crazy, which is why we didn’t incur the wrath of the chicken snake that day at the party. My snake book says that rat snakes are “ill-tempered” and “will readily defend themselves” when provoked. In our case, no defense was necessary, since we were all too busy eating and drinking to notice the thing, much less provoke it. Also, I think the snake was just biding his time. The species has been known to climb trees as high as forty feet in search of birds and the contents of their nests. As it happened, the lunch tables’ very chic centerpieces were abandoned nests collected from the wilds of a typical Delta backyard. The nests were empty, of course, but the snake didn’t know that. What he knows is that he and the birds (and the bears and the deer and the gators and on and on) still own the place. The rest of us are very recent visitors.