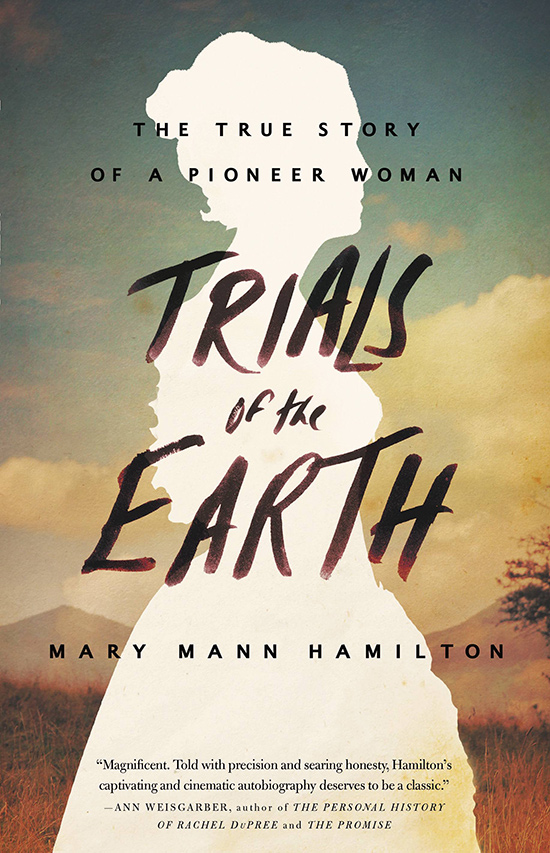

Everybody knows the stories of pioneers Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone, but aside from Laura Ingalls Wilder’s fictionalized Little House on the Prairie children’s books, we don’t often hear tales from the female side of the American frontier. Enter Mary Mann Hamilton (1866c.–1936) whose newly released writings, Trials of the Earth, are the only known first-person account of a woman’s struggles on the Mississippi Delta frontier, which was still largely uninhabited after the Civil War. From making a tent-home for her family along the Sunflower River in western Mississippi to cooking 250 pounds of bear meat “every way I could think of,” Hamilton’s life was nothing short of a pioneering marvel. So is the story of how the book came to be.

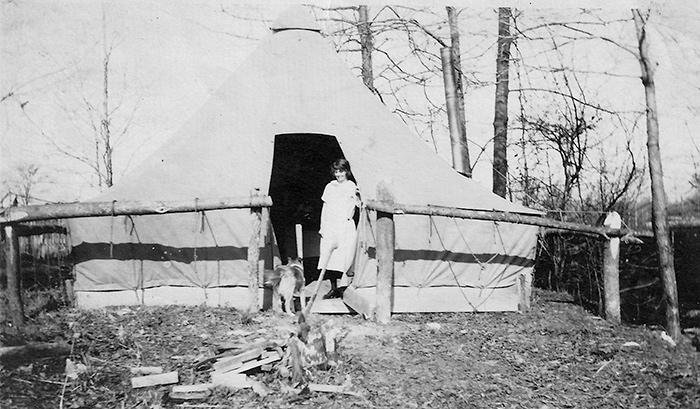

Mary Mann Hamilton in front of her family’s tent in Mississippi.

Late in her life, Hamilton’s neighbor and friend, Helen Dick Davis—who was also an editor—encouraged Hamilton to write down her recollections. Davis entered an early draft of the memoir into a competition sponsored by Little, Brown in 1933. It didn’t win and was seemingly forgotten. In 1992, the University of Mississippi Press discovered a copy of the manuscript and published it, unbeknownst to Hamilton’s family. The Hamilton estate eventually secured the copyright and was able to bring the story full circle by publishing it with Little, Brown—the same company that had first rejected it.

In the preface, Davis wrote: “At the very end of the book, when she speaks of dying, she is still able to say, innocently and with no thought of irony, that she will soon be going to a better world if such can be.… In spite of everything, Mrs. Hamilton has found this world good, and so this is a book of much laughter as well as tragedy.”

Hamilton’s great-grandson Kerry W. Hamilton, who helped bring Trials of the Earth to print and is working toward a possible film adaptation, shares some of his favorite details from the memoir:

The Mississippi Delta is almost like its own character in the memoir—what does Mary teach us about that region?

She wasn’t the first woman to live in the Mississippi Delta, but she was the first white woman to live in the area she did [near today’s Delta National Forest]. It was wooded swampland—total wilderness where my great-grandfather thought he could make a fortune clearing land and turning it into farmland. Back then, cotton was more valuable than oil. The Delta drew immigrants from all over, and it was a gumbo pot of cultures.

Photo: Courtesy Kerry W. Hamilton

Frank Hamilton and a logging team.

How does Mary fill a void in our understanding of Southern history?

She set the groundwork for what we think of as a strong Southern woman. When she arrived at the frontier, she might not have been strong at first, but the Delta changed her and molded her. It made her look at the world around her and learn what she needed to survive for herself and her children. I think she found her independence and didn’t always rely on her husband. She reminds us that in the South, the woman is often the center of the family.

From left: Mary Mann Hamilton, likely on her wedding day; her husband, Frank Hamilton.

How do you think she did it all?

Tenacity. It was just tenacity. I don’t know how she put up with what she put up with. She took what she knew from her upbringing. Her family had a boarding house in a small town in Arkansas and she ran it starting from age seventeen, when her father died and her mother was ill. She knew how to put out food for sixty or seventy people in a day. When she met my great-grandfather and they moved to the Delta, they lived in tents. She cooked for sometimes a hundred people at a time. She would use a barrel of flour in a day. Her husband hunted and she learned how to use every part of whatever he killed—even a bear.

Photo: Courtesy Kerry W. Hamilton

Mary Mann Hamilton later in life.

What is one of the most memorable stories that Mary wrote about?

My favorite part is the flood. She woke up in the middle of the night and she thought she heard a snake in the house. It was actually water hissing when it hit the coals in the fire. When she put her feet down out of bed, they were standing in water. She and her husband and children got out of the house, and he took her to the highest ridge. He put a chair on a huge stump and she sat there with two of the children. He left with two more of the children in a boat to find help, knowing that the water wouldn’t rise too high to hurt them because the stump was six feet off the ground and five feet wide. But while they waited, the water rose so high that when my great-grandfather returned, she was standing on the chair with one child standing with her and the other in her arms. That will be the scene that gives everyone chills.