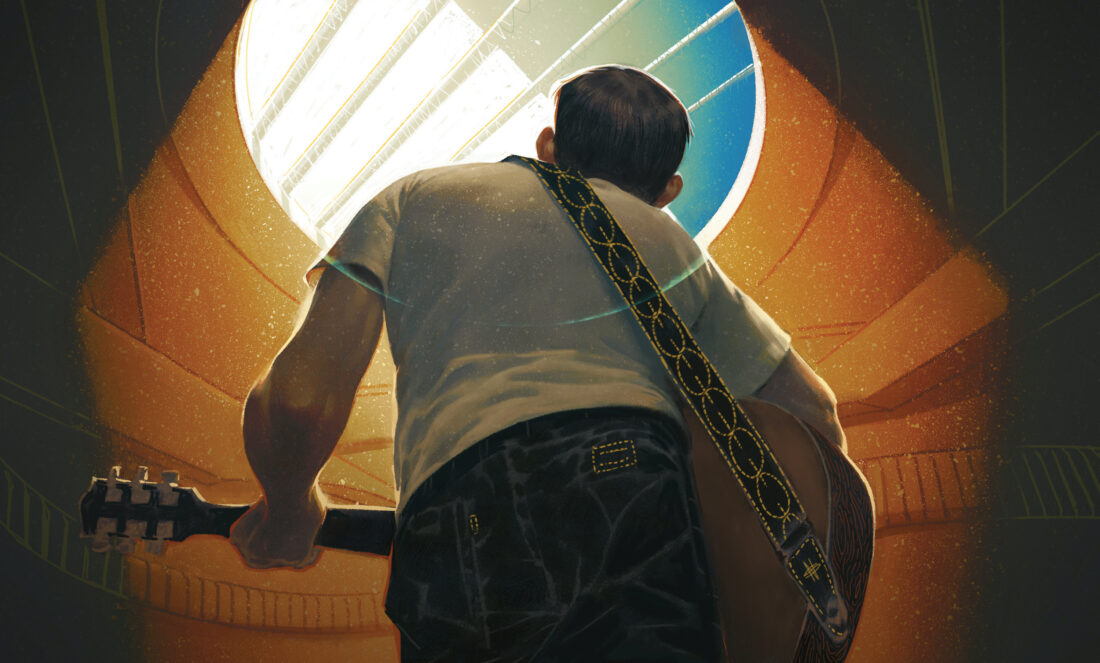

I have no clue what the upstairs neighbors must have thought. I wouldn’t call what I was doing at the time singing—more like a semimelodious howling while strumming a guitar. Back then I correlated sincerity with volume, and at twenty-three, I was nothing if not sincere.

That spring, I had taken a semester off from seminary and was spending my days on Long Island with my terminally ill mother, reading William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and George Herbert. I was trying my hand at writing too. Poems, songs, and short stories rushed out with urgency. Those months of anticipatory grief became a strange limbo. I tried to savor each moment, but death cast a long shadow.

When the doctors found Mama’s initial tumor, under her arm, they thought it might be breast cancer, a diagnosis she had always feared. A needle biopsy proved inconclusive, but within a month, the tumor had expanded from the size of a quarter to a mass five or six times larger. Only after the oncologist removed it did we know exactly how bad the news was: melanoma.

So now I was living with her during her second experimental treatment. She worked in fashion in New York City, where she had moved years after she and my father divorced, and as caregiver, I wanted to help her keep her job as long as she wanted. She toiled twelve- and thirteen-hour days, taking the train back and forth. When she came home, she looked pale, a ghost.

While she was gone, between cleaning the house and buying groceries, I bellowed the same songs to bolster my spirits. “Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing,” its old melody as grounding as the lyrics. Jerry Jeff Walker’s “Gettin’ By,” with Walker’s signature wit—“Gettin’ by on gettin’ by,” which most days, I was hardly doing. And the song that buoyed me more than any other—that folk classic “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” The lyrics both soothed and troubled, taking me to where I’d soon be: like the narrator, watching the undertaker come “to carry my mother away.” I needed to hear the voice of someone who’d been there, at the window, aching for their parent; at the graveside even, where sorrow can’t be hidden and must only be endured.

Originally a hymn written in 1907, “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” entered the vernacular of the South by way of A. P. Carter, the Virginia-born founder of the Carter Family country act and the songwriter of such tunes as “My Clinch Mountain Home.” In the folk tradition, Carter often adapted older melodies and gave them new lyrics, as he did with the song he originally retitled “Can the Circle Be Unbroken.”

Folk songs, like grief, contain truths broadly felt, and yet both have elements that inflect differently based on a person’s experiences. Perhaps this fusion of the personal and the universal is why songs in our folk tradition often have so many lyrical variations. These songs belong to all of us, even as they belong to each of us.

The tune to “Circle,” for example, appears on Harry Smith’s 1952 compilation, Anthology of American Folk Music, as a 1928 recording of Elders McIntorsh and Edwards’ Sanctified Singers performing a song titled “Since I Laid My Burden Down.” Their version begins with the words “Glory, glory, hallelujah, since I laid my burden down.” Taj Mahal opens with those lyrics on the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s 2002 Will the Circle Be Unbroken, Volume III, before singing the Carter lyrics alongside Alison Krauss and Doc Watson. On 1989’s Volume II, Nitty Gritty’s Jimmy Ibbotson pens a new verse, one that honors the ways “Mother Maybelle,”A. P. Carter’s guitar-picking sister-in-law and Johnny Cash’s mother-in-law, has taught the “hymns of faith.” “Hear the angels singing along,” Ibbotson invites—for grief and loss don’t have the final word.

The experimental treatment bought us a year of good time with Mama, but when the melanoma returned, it did so with a fierceness. She was living back in our home state of South Carolina at that point, and my brother Shoan and I checked her into the cancer wing of a Spartanburg hospital. Her liver, they told us, was full of tumors.

As dark as those days were, we still found sweet moments in the hospital. Old jokes and memories recounted. The doctors gave Mama boatloads of Marinol, the artificial marijuana derivative that’s supposed to make cancer patients hungry—like a hyped-up version of the munchies. We got a kick out of Mama’s hankering for Chick-fil-A biscuits, Krispy Kreme doughnuts, and mint-mocha Frappuccinos. Melanoma couldn’t abscond with all our joy. When she died, though, I felt bereft. Lost.

I knew I wanted to speak at Mama’s funeral and to sing “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” as it had offered such comfort already. But when I got up front with my guitar, I could hardly make it through the song. I stumbled through the verses, mangled chords. Then the congregation joined me in the chorus, and suddenly, I didn’t feel so alone. There we were, gathering to mourn, our voices becoming one.

When I sing that song now, I usually close my eyes, because it’s become as much a prayer as anything. In that darkness, I’m not just listening to my own voice. I’m listening for where the song resides: close to my heart, where it has remained a balm when someone else I love is “carried away.” When a cousin left us before his time; two winters ago, when a dear friend died of cancer.

Then, in 2022, my family and I happened to be visiting my father in South Carolina from our home in Nashville when he began to feel nauseated. His health had been precarious all my life, partly due to a form of rheumatoid arthritis, so that was not out of the ordinary. When he’d remained in bed for twenty-four hours, I checked his blood pressure. It was very low. He resisted an ambulance, but we called one anyway. Something similar had happened twice in the previous year. Surely, we thought, this would end as it had before: Dad would get rehydrated, his blood pressure would stabilize, and he’d be home in a day or two.

When I arrived at the ER, he was in excruciating pain. The cardiologist worried he’d had another heart attack. While this shook me, again, I wasn’t totally unnerved. Dad had experienced heart attacks before, an aortic intramural hematoma, a laundry list of other comorbidities related to arthritis. He’d had quadruple-bypass surgery. He had gone into cardiac arrest at my Nashville home in 2016, and I performed CPR on him. He coded five times but survived. The doctors used words like “miracle.” Dad had come close to death so many times, it seemed he’d always pull through.

The doctors finally decided he must be bleeding internally. They asked my brother Darrin and me to leave so they could run more tests. I told Dad I loved him and that we’d be outside. A moment later, I heard him scream, then the heart monitor flat-line. The team started CPR and defibrillation. I contacted family and friends, asking for prayers. I prayed myself. I cried. I listened as they tried to bring Dad back. They could get his heart started, but it wouldn’t keep beating. They stopped. He was gone.

Every time I practiced “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” for Daddy’s funeral, I broke down with the guitar in my hands. At times, I left his house to get away, to drive through the foothills. As I curved around roads where my memory filled in the peach trees long gone, I’d sing the song, a lump the size of a pit forming in my throat, preventing me from getting through the verses.

I’d invited a friend, a Baptist minister, to lead the hymns for the service, and he and his wife agreed to sing along with me—if I faltered, they could keep the song going. And so after I’d preached Dad’s funeral sermon, I draped the guitar over my shoulder and began, changing the lyrics, like so many before me, to make the song my own.

I was standing by my window

On one cold and cloudy day

When I saw that hearse come a-rollin’

For to carry my daddy away

My eyes closed. I expected to lose the lyrics, raw as I felt. But the prayer of the song cradled me, as it had in those days before Mama’s death. My friend and his wife joined in that prayer, their voices lifting mine. The congregation’s voices then united with ours in the chorus. All of us longing for our broken circle of friends and family to be made whole again. And for a moment, it was.