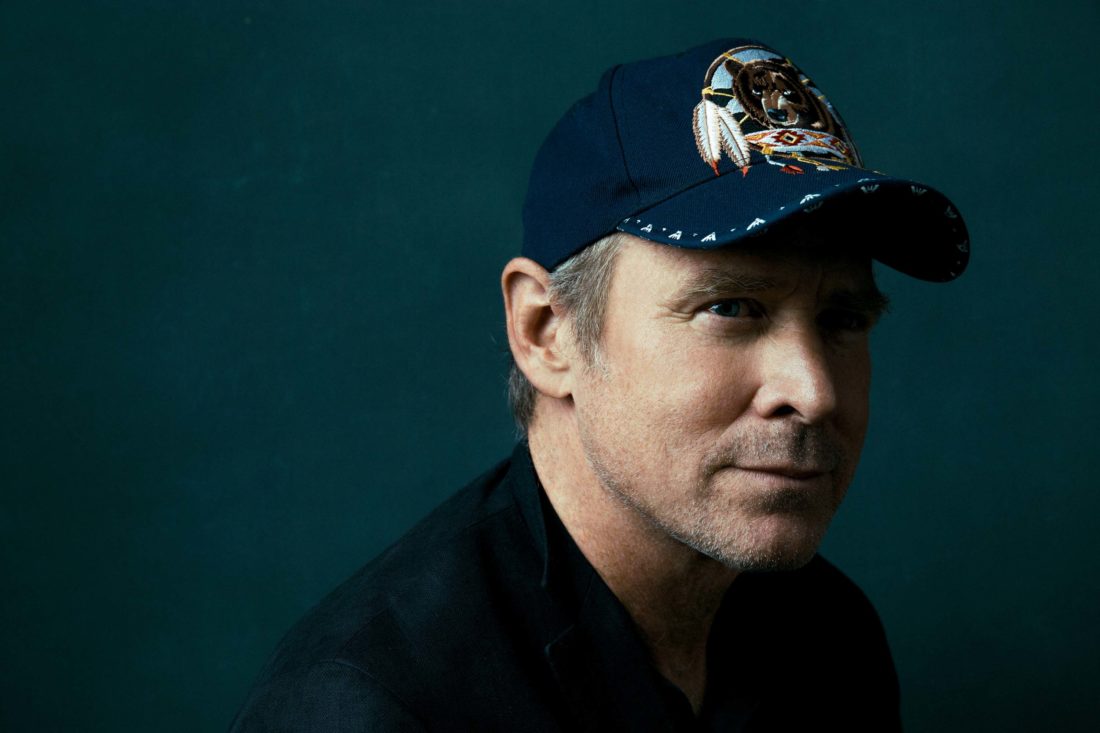

You most likely recognize Will Patton’s face—you may have seen the prolific actor with Bruce Willis and Ben Affleck saving Earth by drilling a nuclear weapon into an asteroid in Armageddon. Or coaching with Denzel Washington in Remember the Titans. The South Carolina native is arguably the only good thing about the Kevin Costner film The Postman. And lately, he’s starred as Garrett Randall in the hit TV series Yellowstone, and in the Oscar darling Minari. But you may also have heard Patton without realizing it: The quiet, knowing grit of his singular voice has come to define the audiobook genre. He reads in a charismatic whisper, the actor of choice to take on the words of William Faulkner, James Dickey, Denis Johnson, Ernest Hemingway, Jack London, Charles Bukowski, Don DeLillo, Stephen King, Jack Kerouac, James Lee Burke, Bob Dylan, and even Woody Guthrie.

You aren’t just reading books into a microphone, are you?

This audio work—it’s almost like secrets can come through this quiet work. There’s a way of influencing even some truck driver who might be thinking in some kind of way. You just lay in a line in a certain way. He’s going to feel something deep inside of himself whether he knows it or not. This quiet audio work is very revealing. Maybe more than other things that actors do.

What sparked your passion for acting?

I was born in Charleston. I grew up all over the place and spent summers there. My dad went to the Citadel. He became a preacher and was a Lutheran minister up until I was about thirteen years old. He was a very rebellious minister—a performer in the pulpit. He read Camus and Sartre. He would stage people in the congregation to challenge him. He was a chaplain at Duke University before he left the ministry. Then he was a fisherman. He ran a charter boat out in Alaska. He went all over the place. He was an English teacher at Dartmouth at one point. I lost track.

From an early age, I couldn’t communicate with anybody unless I was onstage. Some people have almost a kind of sickness, which leads them to health by acting. Mine came out of shyness. My dad’s came out of something else.

Do you connect to Southern literature?

One of the things my dad gave to me was a love of Faulkner. He built me up to Absalom, Absalom!, which is like the crescendo. And Flannery O’Connor, of course. Those two were huge in my discovery of literature. There’s something inside of them that is so layered.

I hope that in this time, people can see the crazy and mysterious truth about the South. As opposed to certain kinds of pictures being painted now by British directors basing their ideas about what the South was on some kind of misinterpretation. They are missing the vast layers of it and the weirdness of it.

How do you approach audiobook work?

The main thing is to just stay out of the writer’s way. Any actor who gets in this booth with that microphone inevitably becomes naked. It’s pretty clear whether someone is being honest or whether the ego is involved. A lot of great film actors get in there. And there’s something that just doesn’t work. It’s challenging to understand what that little meter picks up at the first breath.

If somebody wants me to record their book, I look at it very carefully. I try not to do anything that I don’t feel a hundred percent about. If it’s a great book, I have to find the place where the writer and I meet. And that brings it to a little different level. So I let it move through me, but I also find out who the two of us are together.

Audio work is an art.

Originally it was thought of as a kind of art form. I remember when I first started doing it, a group of producers would be sitting on the other side of the glass watching like it was a performance—an intimate one-man show. It raises the stakes. Now you’ve got a lot of people with their studio set up in a closet. Now they say, “How many hours do you think this is going to be? How many days?” It’s like when I’m working on a movie, and someone goes, “Oh, thank God, it’s almost Friday.” And I’m like, “What are you even doing this for? You’re thinking about the weekend? What is the work? How can it be the most it can be?”

You are the voice of literary masters. Do you feel a sense of responsibility?

Absolutely. When I am approaching an audiobook, I approach it just like I do theater or a film in terms of my preparation. I try to put myself in a state where I live with that book in my head for the days leading up to it. It becomes all I’m doing while I’m doing it. I’ve even gotten in trouble [on set] because they’ll say, “Will can’t make it for this leg. He had to change his schedule around on this TV thing because he’s doing an audiobook.” And they’re like, “What!” But this is just as important to me. If it’s a good writer, that writer deserves that kind of attention.

What are you reading right now?

Just for me: Peter Matthiessen’s The Snow Leopard. That old World War II book Norman Mailer wrote, The Naked and the Dead. Then this new Malcolm X biography, The Dead Are Arising.

What keeps you going during an audiobook project?

From an early age, my favorite thing was to live inside of a book. And now I get to do so, but on this further level where I am inhabiting the book viscerally. What could be better than actually living these great works of literature? It’s phenomenal.

Your work appeals to so many listeners.

I remember one time I was having a hard time with a particular book or something. And the producer on the other side of the glass said, “Come on, Will, the truck drivers are gonna love it!” Then I was driving across the country one time, and I saw a bunch of my audiobooks on a rack in one of those truck stops. And I was like, Okay. I’m gonna start putting some little secrets in these books.