Strictly speaking, the term “Florida Highwaymen” describes a collective of African American landscape artists—including at least one “highwaywoman”—who sold their paintings door to door along Florida’s Route 1 from the 1950s to the 1980s. But there’s more to the term. How viewers interpret their story, like all folklore, feels like a function of who is doing the telling.

The artists are the subject of the Orlando Museum of Art’s traveling exhibition Living Color: The Art of the Highwaymen, which next opens at the Tampa Museum of Art (November 19—March 28, 2021). In this instance, the organizers interpret their cultural contributions through the lens of longtime Highwaymen collectors. “What I decided to do,” says the guest curator, author, and photographer Gary Monroe, “was go to five of the primary collectors of this art and curate through their eyes and ideas.”

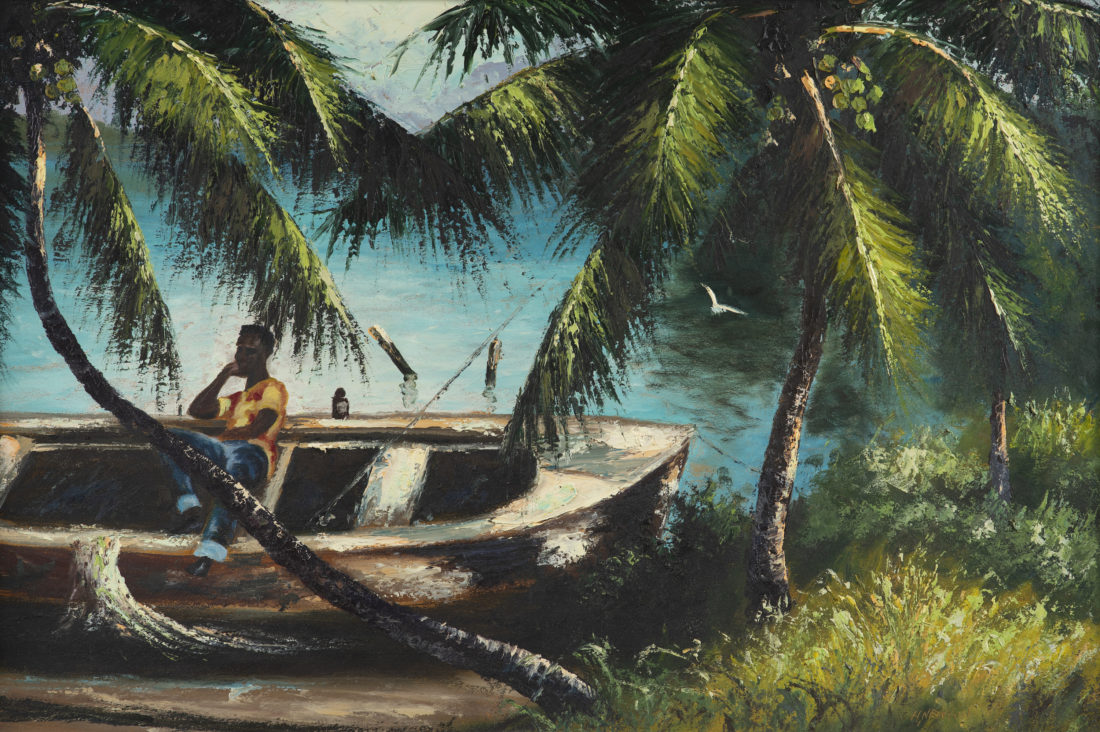

Perhaps you’ve seen Highwaymen paintings, characterized by vibrant renderings of saturated sunsets and the sabal palm trees and backwater lagoons that filled Florida’s natural landscape before major development. Living Color brings together one hundred of these paintings by a core group of the Highwaymen, including searing backcountry sunsets by the lone female artist, Mary Ann Carroll, windswept beach dunes by Alfred Hair, and squall-driven shorelines by Harold Newton.

The twenty-six artists considered Highwaymen have amassed a devoted following, as Monroe has chronicled beginning with his first book, The Highwaymen: Florida’s African-American Landscape Painters. However, critics and art institutions largely overlooked the artists during their most productive years.

Alfred Hair and Harold Newton are two of eleven core group members on which the exhibition focuses. “Newton painted classically, and he followed the cue of A. E. Backus,” Monroe explains. Backus, a white, progressive regionalist in Fort Pierce in the late 1950s and early 1960s, influenced many young artists in the region.

While Newton adhered to the classical ideals of landscape painting, Hair, who is the only Highwayman to have actually studied with Backus, developed his own fast-painting technique, which, Monroe says, “bastardized those cherished concerns” of technical and compositional perfection. Developed to provide an economic alternative to life laboring in the citrus fields of the Jim Crow-era South, fast painting allowed these artists to sell paintings as quickly as possible.

It’s this backstory, along with a nostalgia, “a longing for a Florida that was less crowded and hectic,” that Monroe notes, in an essay in the exhibition catalogue, that inspires each collector’s passion for and personal connection to the subject matter. But, he insists, “It’s not just a feel-good, folksy story,” but one that led painters such as Hair to actually push the aesthetic development of American landscape painting into bold new directions.

Furthermore, Monroe argues, part of the Highwaymen’s legacy, preserved by predominantly white collectors, lies in the Florida landscape’s association with the postwar American dream. “Imagine being nineteen or twenty years old doing calisthenics on South Beach, and you’re basically looking at paradise before you go off to a horrible war,” Monroe says. Returning soldiers, he imagines, might have purchased Florida property from a corporate brochure, sight unseen. Finding themselves five miles inland in scrub country, instead of on a beachfront, as advertised, the closest they might ever come to that dream are the vivid windows into an untouched Florida paradise that the Highwaymen rendered.