Christmas is as much a part of the foundation of the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina, as the Appalachian mountain acreage where it stands.

“From the very beginning of construction, the end date for the opening was always Christmas of 1895,” says Leslie Klingner, Biltmore’s Curator of Interpretation. “It wasn’t like George Vanderbilt started building and said, Oh maybe it’ll be done by then. It was the goal. That tells me a lot about how George felt about Christmas.”

Nearly a century and a half later, the Biltmore’s holiday traditions are still the stuff of Southern legend. This year’s season begins Friday, November 6, and will include festivities sprawling out across the 8,000 acres that surround the 250-room mansion, a luxuriously appointed Banquet Hall, and a thirty-five-foot Fraser fir.

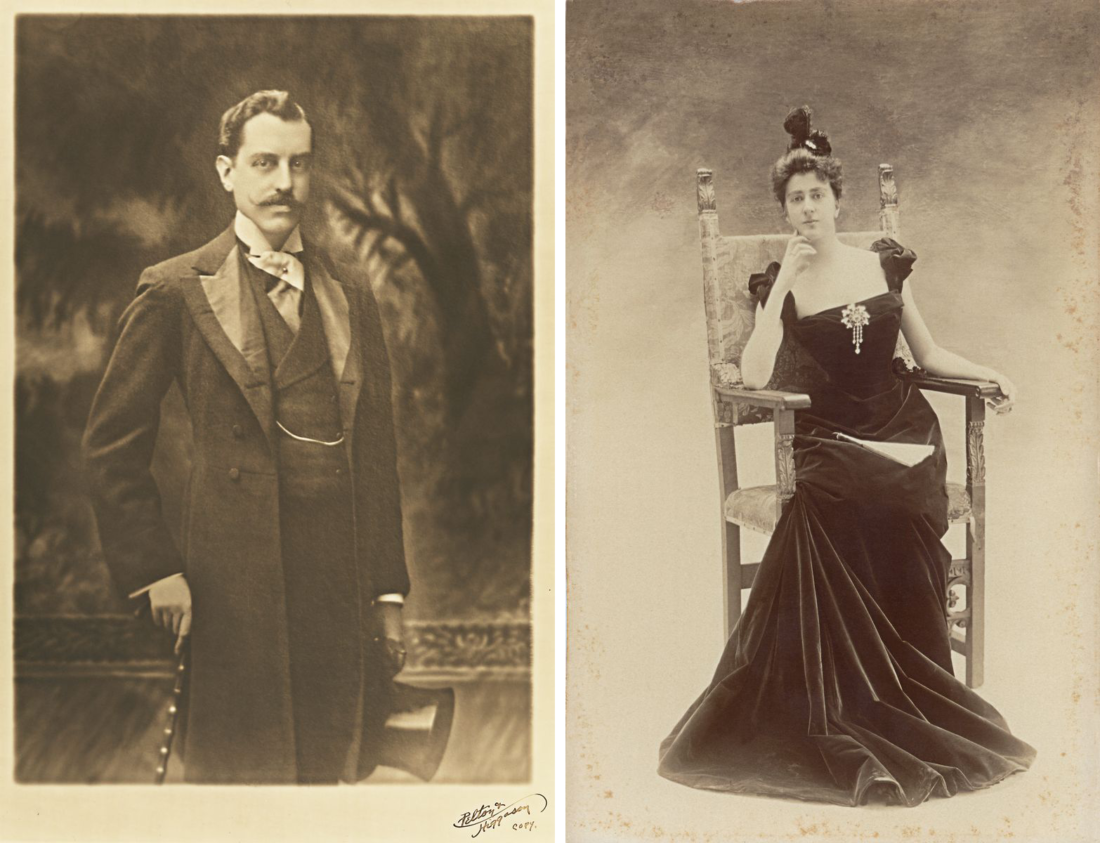

But first, George W. Vanderbilt II, an heir to a massive family fortune built on steamboat and railroad enterprises, had to set it all in motion. In the 1880s and 1890s, he assembled hundreds of parcels of land and began constructing the house in 1889. He hired local builders, landscapers, and house staff. Although he managed much of the work from afar, in October of 1895, he moved to the estate to oversee the finishing touches.

Biltmore has records of the correspondence between a manager and his very particular boss. “The estate manager says it has to be a very tall tree or it would be dwarfed by the Banquet Hall height, and I love that George wasn’t like, Oh just make it happen—he is getting the reports, thinking about the tree, and involved in every detail of the decorations,” Klingner says. Vanderbilt instructed workers to gather fragrant greenery and mistletoe from surrounding farms. He ordered pots of poinsettias, rare at the time in the United States, which would have seemed entirely exotic to the staff. “We still always fill that beautiful sculpture in the center of the Winter Garden with poinsettias,” Klingner says. “It’s called Boy Stealing Geese, and it was put in just so that it could be there for Christmas.”

The estate ledger shows that Vanderbilt required “enough fish to make a course for fifty people every day, and lobsters for the same number twice a week.” The farm manager asked to increase the amount of butter on hand, and he ordered black walnuts, chestnuts, celery, honey, and one especially Southern staple by accident. Forty pounds of grits arrived at the estate by mistake, but the manager, according to the ledger, said he could “make use of them.”

Vanderbilt built a special train station to drop visitors right in the heart of his Biltmore Village, and the first guests arrived for Christmas Eve celebrations in 1895. George’s mother, Maria Louisa Kissam Vanderbilt, stepped out to see her son’s creation, along with dozens of other family and friends—the largest gathering of the extended family since George Vanderbilt’s father, William Henry Vanderbilt, died ten years earlier.

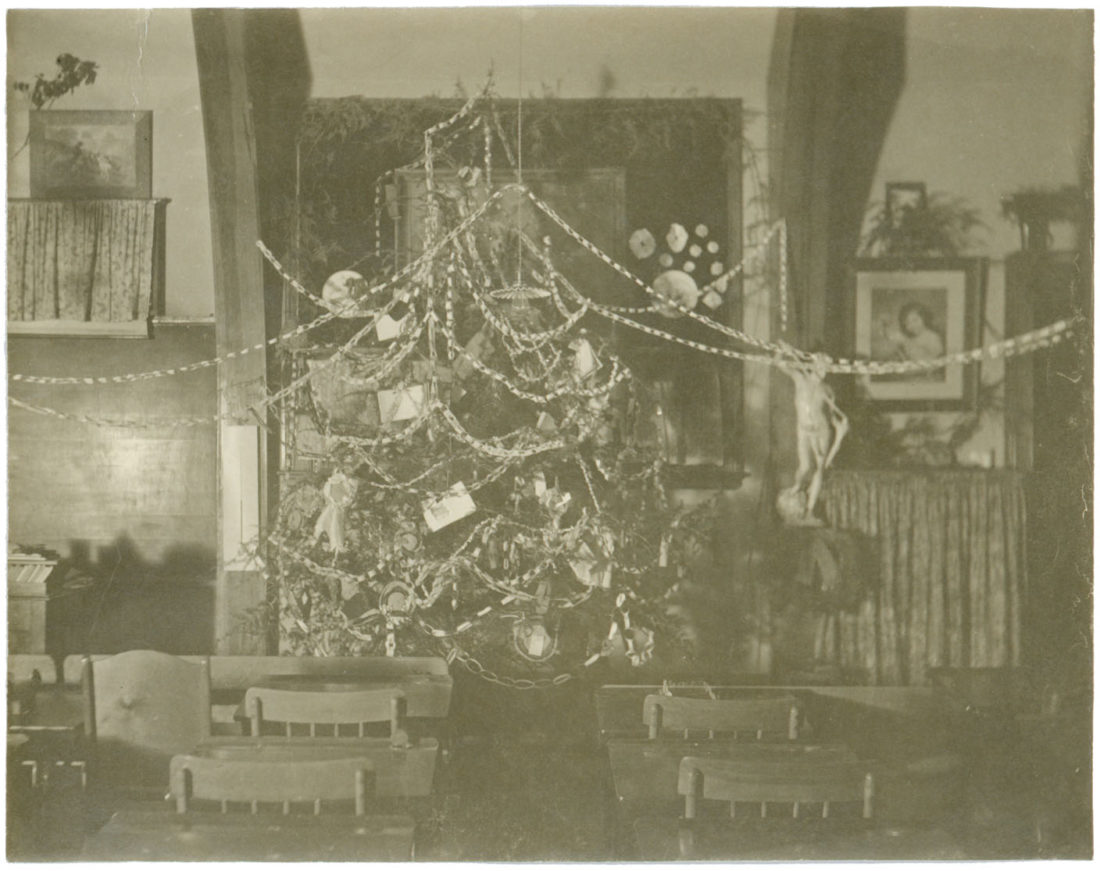

“The guests gathered in the Banquet Hall, where there was a Christmas tree forty feet high, beautifully decorated,” noted the Asheville News and Hotel Reporter at the time. “Under the tree was a round table piled high with gifts, which the guests exchanged with one another. The Imperial Trio furnished music for the occasion, and the rich costumes of the ladies, the soft lights and the tastefully draped garlands of evergreen and mistletoe, interspersed with the shining leaves and red berries of the holly, created a scene beautiful to look upon.”

George Vanderbilt’s niece Gertrude Vanderbilt, twenty years old, kept notes and diagrams of seating arrangements for dinners she attended during her social season—her dinner at Biltmore was the 193rd formal dinner she attended that year, and she marked the places of twenty-seven dining family members, including “Grandma” and “Uncle George.”

The next day, on Christmas, Vanderbilt threw another Banquet Hall bash to honor some two hundred workmen and their families—and gave a gift to every child in attendance. (The holiday party for Biltmore employees and their families remains a treasured tradition.)

When George married Edith Stuyvesant Dresser three years later, the bride didn’t miss a beat, expanding on Vanderbilt Christmas traditions and becoming a meticulous record keeper of the gifts given to each employee’s child over the years, Klingner says. As much as possible, Edith tried to purchase gifts from Asheville makers and retailers, and often wrapped and wrote the gift tags herself.

“Edith stepped in and instantly brought this whole other level of warmth and connection,” Klingner says. “As a surprise to George, she brought in entertainment and performers, and there is a newspaper article about how he sang and would heartily laugh—he’s pretty quiet and introverted, but I love how delighted he would have been at surprises like that, his wife helping it all play out across this whole magical world he created.”

Among the traditions that have endured, such as the poinsettias, the giant tree, and kids’ gifts, another has lingered, although the staff isn’t quite sure when it started. For generations, Vanderbilt family members have tucked a pickle-shaped ornament among the tree’s branches. “The hidden pickle convinces onlookers to stop and more deeply appreciate the beauty of the ornaments and the greenery,” Klingner says.

And while decorations continue to delight generations of visitors to Biltmore, perhaps no one has described the sensation better than one of the guests at that very first Christmas in 1895: “My mind is like a sponge that has absorbed all it can, and [I] find still more,” Vanderbilt’s friend Willie Field wrote to his mother. “We arrived at Biltmore after dark … With the moon shining outside of the windows over the hills in the distance … intoxicating…”