Editor’s note: In the forthcoming June/July 2020 issue of Garden & Gun, the author Holly George-Warren wrote this ode to Threadgill’s, a longstanding restaurant and music venue in Austin, Texas. Sadly, its owner, Eddie Wilson, just announced that he will be closing Threadgill’s for good. “This whole pandemic has been like a kick in the gut that bent me over,” he told the Austin American-Statesman. Janis Joplin found her footing at Threadgill’s, as did many other beloved Texas artists. When we went to press, we didn’t know the “Our Kind of Place” tribute piece would also end up serving as a eulogy to a Southern institution.

In 1993, for the first time, I opened the screened door and walked into Threadgill’s, a down-home restaurant and longtime music hot spot housed in a former Gulf station in Austin, Texas. Pointing to this back entrance was a vintage neon arrow, hanging next to the words HOWDY STRANGER. I wouldn’t be a stranger for long.

The then-sixty-year-old joint’s wood floors had been trod by an evolving clientele, beginning with salt-of-the-earth beer drinkers who were then joined by college kids, beatniks, pickers, and protohippies in the late 1950s. Thanks to its original proprietor, Kenneth Threadgill, a spirit of inclusion overcame the era’s pervasive culture clash, an ethos handed down to its current owner (and former patron), Eddie Wilson. After that first visit, I was hooked.

Today’s succotash of customers crosses every cultural boundary: cowboys and truckers, gamers and quilters, strippers and schoolteachers, punk bands and prayer groups, bodybuilders and techies—the colorful hodgepodge of folks who’ve kept Austin weird. Threadgill’s opened as a gas station in 1933 and then became a beer joint with snacks (pickled eggs and pigs’ feet). After Wilson took over in the 1980s, he transformed it into a country café, its home cooking as big a draw today as its live music scene. Over almost thirty years of trips to Austin, it’s always been my first stop: a place with old-school beer-logo wall clocks where time has stood still.

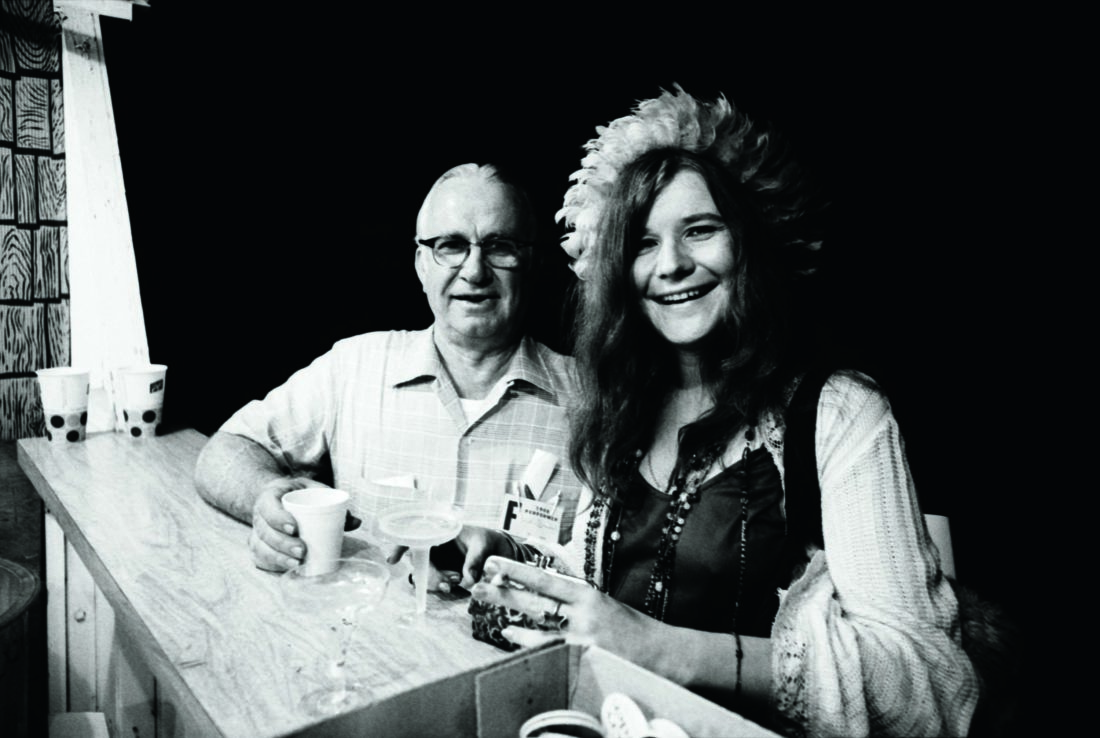

I first heard about Threadgill’s via the Janis Joplin origin story: The Port Arthur native blossomed from University of Texas art student to powerhouse blues singer stomping on the floor here in 1962 with bluegrass combo the Waller Creek Boys. Walking through the dark-wood corridor to enter the dining room, I like to gaze upon a shrine of sorts to Joplin and Threadgill, her mentor. In photos together, the pair look like silver-haired daddy and wild-child daughter.

A Jimmie Rodgers fan and amateur yodeler, Threadgill hosted Wednesday-night “hootenannies” that a nineteen-year-old Joplin and her trio started crashing. He loved everything she sang, from Kitty Wells to Lead Belly to Bessie Smith, as well as her own “What Good Can Drinkin’ Do,” the first song she ever wrote. At Threadgill’s, Joplin, who’d only sung for friends and on campus, found her true calling and her first champion.

Over the decades, Threadgill’s has hosted a who’s who of other Austin music luminaries. My first visit was on assignment to profile the Lubbock-born high-lonesome-voiced singer Jimmie Dale Gilmore, who resurrected his dormant career on the Threadgill’s stage in 1988 when Wilson re-created the old Wednesday-night “singin’ sessions.” And my first interview with Wilson turned into a twenty-seven-year conversation. Inspired by Kenneth Threadgill, he had originally jumped into the hospitality business in 1970 by opening Austin’s Armadillo World Headquarters, the raucous live-music venue where dope-smoking hippies and Shiner-guzzling rednecks bonded over their mutual love of Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings. Ten years later, he bought and rebuilt Threadgill’s, which had sat abandoned since ’74, when Kenneth’s wife, Mildred, died and the bereft Threadgill shut it down. To accommodate overflow crowds, Wilson eventually added a classic stainless-steel diner extension. (He also opened a second, larger Threadgill’s next to the Armadillo’s old location; doomed by Austin’s ongoing real-estate boom and soaring property taxes, that outpost closed in December 2018.)

Today, the original Threadgill’s looks and feels much as it did when I first stepped through the door more than two decades ago: long tables covered in red-and-white-checked oilcloth that seat three generations of family members, with room for overflowing plates of fried chicken livers, meat loaf, catfish, creamed corn, turnip greens, butter beans, and fruit cobbler. The diner section features a traditional lunch counter. Waitstaff still wear red gas-station-attendant shirts, and the menu continues to list more than thirty vegetable dishes, many of their recipes derived from Wilson’s Mississippi-born mother, Beulah, whose portrait graces the front.

I still prefer the main dining room, where I can settle into a cozy wooden booth and peer at the walls festooned with portraits of Joplin and Threadgill, framed newspaper clippings, kaleidoscopic neon signs for Pearl and Lone Star beer, and Armadillo show posters for Willie Nelson, Commander Cody, and Asleep at the Wheel. With the aroma of chicken-fried steak in the air, it’s hard to rein in your food order—the five-vegetable plate or the meat-and-three? Another margarita or a piece of buttermilk pie?

And then there’s the music. The Sunday gospel brunch transports you with the transcendent sounds of harmonizing and testifying. Several nights a week, you can still see such premier Austin singer-songwriters as Michael Fracasso at intimate acoustic performances.

I first heard Fracasso’s yearning tenor there in the mid-1990s, backed by master fiddler-guitarist Champ Hood as they perched on the tiny stage surrounded by a wooden corral-style railing. Twenty-five years ago, the exquisite Americana artist Carrie Rodriguez got her start on that same stage at sixteen, playing “Cotton-Eyed Joe” on fiddle beside the great Texas yodeler Don Walser, whose packed residency at Threadgill’s enabled him to finally become a full-time musician in his sixties. When I saw him perform in 1994, I thought the XXXL-cowboy-shirted and Stetson-topped Walser could have been Kenneth Threadgill’s younger brother. He held impossibly long, high-pitched yodels as he strummed his acoustic, with Floyd Domino playing barrelhouse-style piano behind him. Gripping a longneck, I felt like I was in a Texas honky-tonk circa 1958. It’s a sound—and a night—I’ll never forget.

When I began researching my biography of Janis Joplin, I made a beeline to Threadgill’s. Eddie Wilson (born the same year as Joplin) had seen her teenage performances there and showed me the spot where she held court. The old bar was gone, but its replacement, suitably scarred by cigarettes and steins, stood in its place. He described the round oak table where she had carved her name alongside her fellow musicians’. We looked at a fading black-and-white photo of her in work shirt and jeans, leaning against a ’38 Chevy, and another shot of her seated next to Mildred Threadgill, who’d handed her a hairbrush to tame her unruly mop. I listened to reel-to-reel recordings of Joplin developing her voice at Threadgill’s, singing “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky-Tonk Angels,” which she introduced as “a hillbilly blues.” Her Bessie Smith twelve-bar blues got just as much applause at the then segregated bar as her harmonizing on “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” The tapes capture beer bottles breaking, fans chattering and clapping, and Joplin arguing with her bandmates about which key to sing in. She sounds completely at ease there—like it’s her home. Just as Kenneth Threadgill always did, Eddie Wilson makes us regulars feel like it’s our home too.

This article appears in the June/July 2020 issue of Garden & Gun. Start your subscription here or give a gift subscription here.