A few days after her death in 2022, I attended the visitation of Clara Muriel Barwick, the cherub-faced woman who taught me to make both applejack hand pies and ambrosia on episodes of A Chef’s Life. I am fortunate not to have had to spend a lot of time at memorials or funerals, but my parents go to some version at least once a week, so I am familiar with the typical, mostly morose run of show. That’s how I know that Ms. Barwick’s celebration of life was different.

She wore a Wolfpack-red suit on her five-foot frame, which was tucked into a shiny casket, also cherry red. At her side lay a few Danielle Steel novels, just in case, and all around her, hundreds of salt and pepper shakers—representing every state in the nation, every holiday on the calendar, and every imaginable Disney character and major Bible figure—dotted every surface available.

This was not the first time I had laid eyes on Ms. Barwick’s extensive collection. While filming at her house roughly a decade before, I had given myself a virtual pat on the back for not being the type of person who accumulated such things—at the time, I considered them meaningless masters of dust collection, also known as trinkets. No, I am selective. I edit down the material things in my world based on need and aesthetic, and have trained my children to identify and loathe “junk” in all its forms.

But that day at the visitation, my minimalist sensibilities proved no match for Ms. Barwick’s salt and pepper shakers, lined up like a lifetime of memories for the taking. Instead of making me proud to be a purger, they made me cry like a baby. On the drive home, with two sets of shakers in tow, four pieces of Ms. Barwick that were now pieces of me, I thought about what my possessions, the worldly things I’ve collected over time, say about who I am.

Sometimes, people collect things with purpose. I imagine Ms. Barwick must have decided during a vacation earlier in her life that she wanted to commemorate the journey, and that a salt-and-pepper set would make for a fine souvenir. On every jaunt thereafter, perhaps she did the same, until searching for the perfect shakers became one of the trip’s highlights. Along the way, her friends and family probably got wind of her affinity for the knickknacks and started bringing her back selections from their own forays out into the world. As her collection grew, so would have her reputation as a collector. Every trinket in Ms. Barwick’s trove marked a moment in her life and told a story about where she had been and what she cared about.

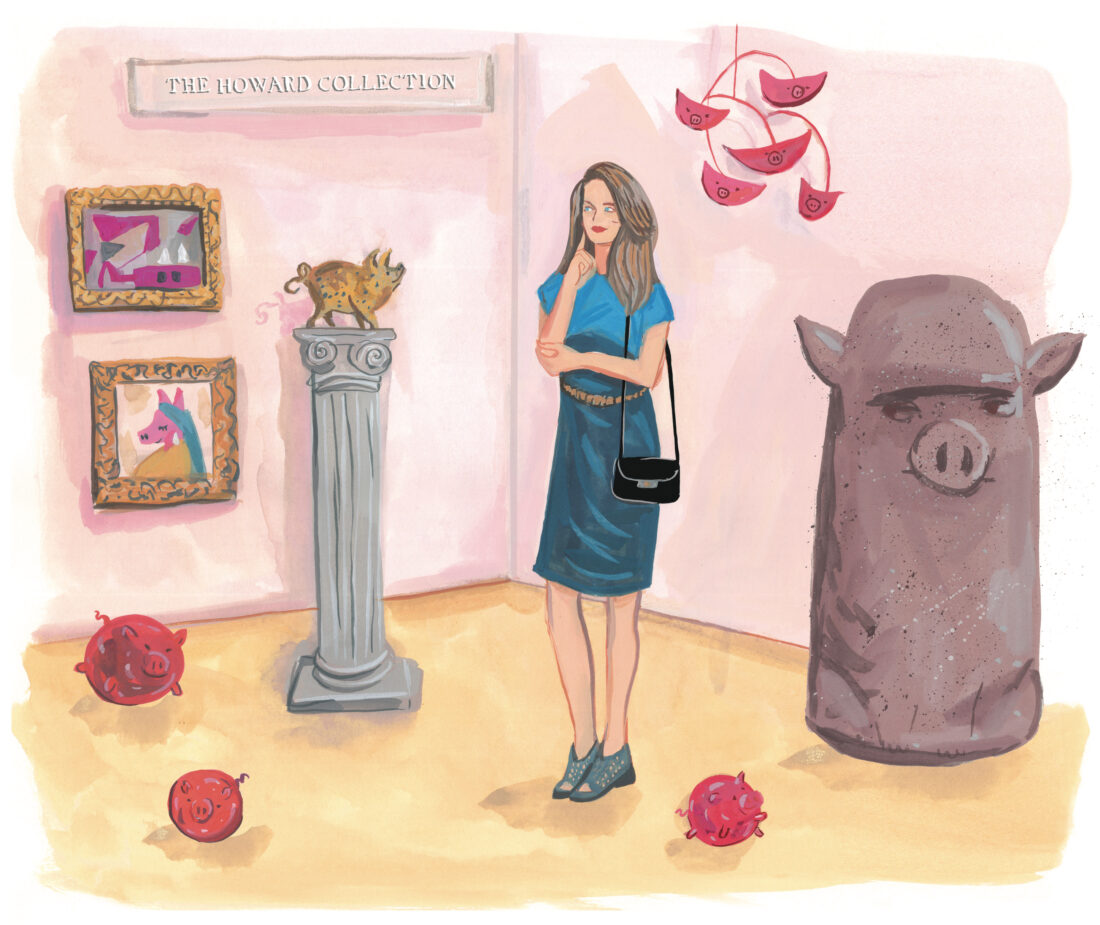

Other times, collections find us. Since the early 1990s, my parents have been hog farmers. Not because they think pigs are cute, or because they have a charcuterie cave, but because that’s just what a lot of tobacco farmers did to make a living after demand for the crop declined. Even so, a lot of people have given my parents over the decades a lot of pig paraphernalia. On our glassed-in porch, the largest piece of “art” for years was a framed photo of two red-skinned pigs nuzzling each other, a gift courtesy of the Farm Bureau, with the caption “Hogs are beautiful.” My parents have also received myriad swine-inspired holiday decorations. Pigs made up to look like bunnies for Easter, pig Santas, pig ornaments that simply mark the year. My favorite pieces, which I am sad to say broke long ago, were rocks glasses printed with two pigs atop each other. That caption read, “Makin’ Bacon.”

At some point, my parents leaned in to the interest projected onto them and started adding to their collection on their own dime. To this day, when you enter the front door of my childhood home, a pair of stone pigs greet you. Their mottled gray backs and pointy snouts used to be totally exposed and a little menacing. Now the pigs are suffocating a little in variegated liriope, but they don’t seem to mind.

All of a sudden, I realized that I already am a collector, one so deeply entrenched I couldn’t see the forest for the pile of enamel utility pans I have cobbled together over the years. I had failed to recognize the bowl of Theo and Flo’s baby teeth, mixed with crystals and a small but growing selection of shark teeth, as the trinket chest it so obviously is. I had chosen to overlook the fact that the decorative walls, wine shelves, and more I have built over the years out of old tobacco sticks—an homage to my heritage—counted. I reminded myself that at one point I had amassed close to fifty spikeless orchids in an effort to save them from their impatient caretakers. And I had gone all ostrich-in-the-sand about the objects I’ve kept and curated, on purpose, that remind me of the darkest, most challenging moments of my life: a singed Oban whisky bottle from the fire at my restaurant Chef & the Farmer, a wooden helmet I bought with tears in my eyes during a failed mother/son trip, a lemon tree I’ve never allowed to thrive given by a former colleague, the mustard-colored bowl my mother used to leave with me overnight when I had a stomach bug, basket-weave flowers that a man on the street in Charleston, South Carolina, offered me the day the general manager of my restaurant Lenoir gave her notice and he could see the worry and defeat on my face.

Perhaps I just didn’t recognize myself as one because I fell for the stereotype. I don’t set out to hunt down artifacts to make tangible every experience, and I’m not prone to turning the piles of personalized wooden spoons, aprons, dish towels, and plates that people have so generously given to me over the years into a personality or identity. I am grateful for and have enjoyed much of that kitchen swag, of course. I’ve just always considered those gifts to be more of a reflection of the way my friends and fans have responded to my work rather than a reflection of my tastes. Instead, it seems, the objects I’ve chosen to surround myself with, the ones I legitimately collect, have found me for better and often for worse, and because of that, they come with a story. It’s the stories I’m trying to accumulate. And if they need to live inside an object in order to live longer, I’ll find one.