“Come on over and look through all my stuff,” Nathalie Dupree told me on the phone last year. The eighty-one-year-old chef and television personality had seen on Facebook that I was moving in town here in Charleston, and coincidentally she was thinking about downsizing. “Take anything you need.” Dupree, who with her husband, Jack Bass, has since moved to Raleigh to be closer to family, took me under her wing—or rather, sent me flying up the stairs to the attic of her then home, just blocks away from my own.

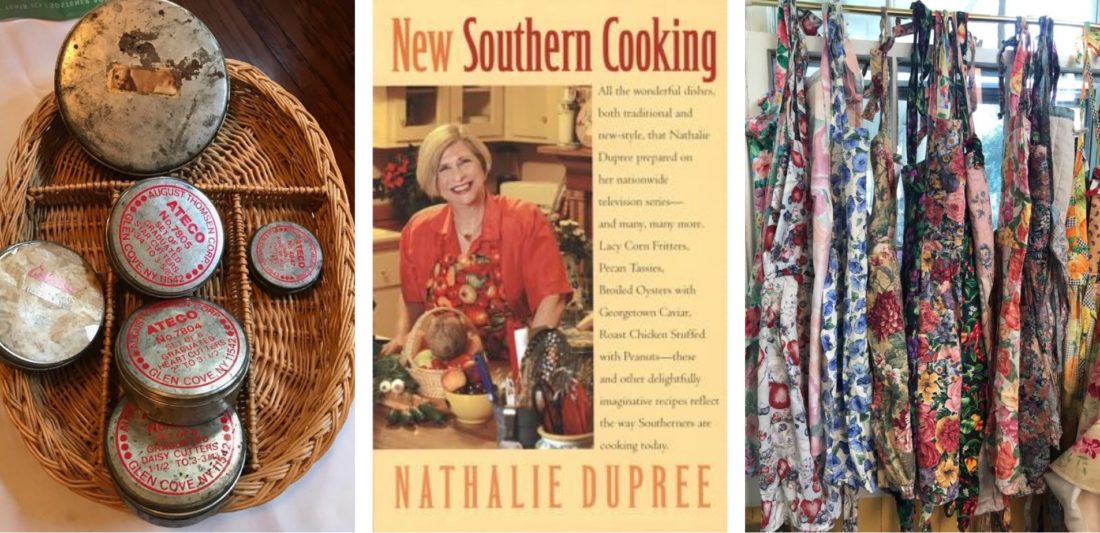

The wider public recently got the chance to sift through Dupree’s culinary treasures, too. At her estate sale in downtown Charleston, she sold dozens of titles from her cookbook collection, colorful aprons, Cuisinart and Le Creuset goodies, gadgets and linens, and every imaginable shape and size of cake pan. A portion of the proceeds went to the Charleston chapter of Les Dames d’Escoffier, an organization that supports women in the culinary world.

I interview people of all professions, including chefs, but I’m not a very confident cook myself. And although I’m a bit of a thrift store regular and collector of old stuff, I didn’t have much in the way of kitchen essentials when I bought my own first home in Charleston. I moved time and again in my twenties, and whatever baking hand-me-downs I had were lost in roommate shuffles or forgotten in the fog of breakups. On any weekday after work, I was much more likely to meet friends at a bar than to cook a square meal. At the time Nathalie Dupree invited me over, I had a shelf of antique crystal champagne flutes, but I didn’t even own measuring cups.

It was clear from the driveway that Dupree’s home belonged to someone who not only lives life well, but completely and genuinely as herself. The sunny yellow Charleston single winked with royal blue diamonds painted on the front gate, and cheerful chipped plates sprouted among tufts of basil and rosemary. “If a dish breaks, I just plant it in the garden,” she said matter-of-factly, and then welcomed me inside.

I’d been in Dupree’s formal front room once before, to interview her for Garden & Gun’s Southern Women book. This time as then, my eyes bounced around the trove of framed art filling every bit of wall. A collection of brass bottle openers and cork screws trailed up and down the door frames and windowsills. Dupree stopped drinking alcohol decades ago, and I told her I was about a year into rethinking alcohol’s place in my own life. She gave a slow, knowing nod and smiled. She sat framed beneath a lifetime of treasures, almost all with a story she could remember, and sipped from her wine glass full of Diet Coke.

We talked about her “pork chop theory,” about how she believes people who might think of themselves as competitors can instead make room for one another, like how the fat from one pork chop feeds the other while they cook together in a pan. And before she sent me up to her attic, she reminded me that while it feels good to receive, it feels even better to give. “I’d like to give you anything you need,” she told me. “And if you find out you don’t need it, give it to someone who does.”

Cookbooks from every decade lined the creaky stairs, spanning Charleston Receipts to The Pioneer Lady’s Country Kitchen by Jane Watson Hopping to Dupree’s own classic New Southern Cooking—she herself has authored fourteen volumes. From boxes tucked beneath the eaves, I kept pulling out beautiful rather than practical objects, delighting in the texture of a worn linen napkin or marveling at a tarnished old rice spoon.

Dupree said that she, too, was drawn to form over function sometimes. While she might take a shortcut such as zapping grits in the microwave, she’ll also linger over the beauty of a blue and white antique platter. She told me stories about dinners with the author Pat Conroy and his wife Cassandra King, showed me the mixing bowl she used as a student at London’s Le Cordon Bleu cooking school, sifted through cutlery dating back to her time directing the Rich’s Cooking School in Atlanta, folded a pile of aprons she had worn on television, and chuckled at the funky little tongs she used for serving escargot. She told a story for every little doodad I picked up while her hands knowingly filled a box with necessities such as baking sheets, a Cutco spreader, “pokey and flippy things, you need lots of those,” and a ruler—absolutely essential for measuring biscuit dough, she said.

Before I could close on my house, Nathalie’s gifts rattled and clanked in the trunk of my car. I thought about how many moves make up a lifetime, about how annoyed I get with my own sentimental self every time I haul boxes from one place to another. Sometimes the stories I tell seem trapped in what I carry from place to place. Other times I look at my junk and imagine how all new gadgets would make me feel closer to some ideal, put-together version of myself I imagine but that I am not.

A few days after my visit with Dupree, my friend Lizzy mentioned she was going to try making biscuits and needed a biscuit cutter. I fished one out of my car. Another friend was baking a pie and needed a bigger cooling rack. Another wanted a metal spatula. If, after one visit to Dupree’s home, I could share goodies out of my car for weeks, just imagine how many treasures she’s passed along to others. I think about her words often, about the fun of receiving, and the greater joy in giving. I respect that she isn’t so precious about things. She just plopped kitchen stuff in my hands and told me to use it or give it away. To her, stuff is just stuff, the means to the end of trying a new recipe, setting a beautiful table for friends, and writing a more textured, colorful story about our lives.

In pictures of the sale, I eyed one of Dupree’s bottle openers, for popping the tops off of beers for friends—Topo Chico for me—when I can finally host a housewarming party. But my cozy kitchen is stocked now with just what I need. A generously sized antique bowl I’ve been mixing biscuit flour in. And a set of bright yellow measuring cups.

Find more information on what sold at Dupree’s estate sale here. Some of her remaining books, including copies of her earliest cookbooks, are for sale at Buxton Books in Charleston.