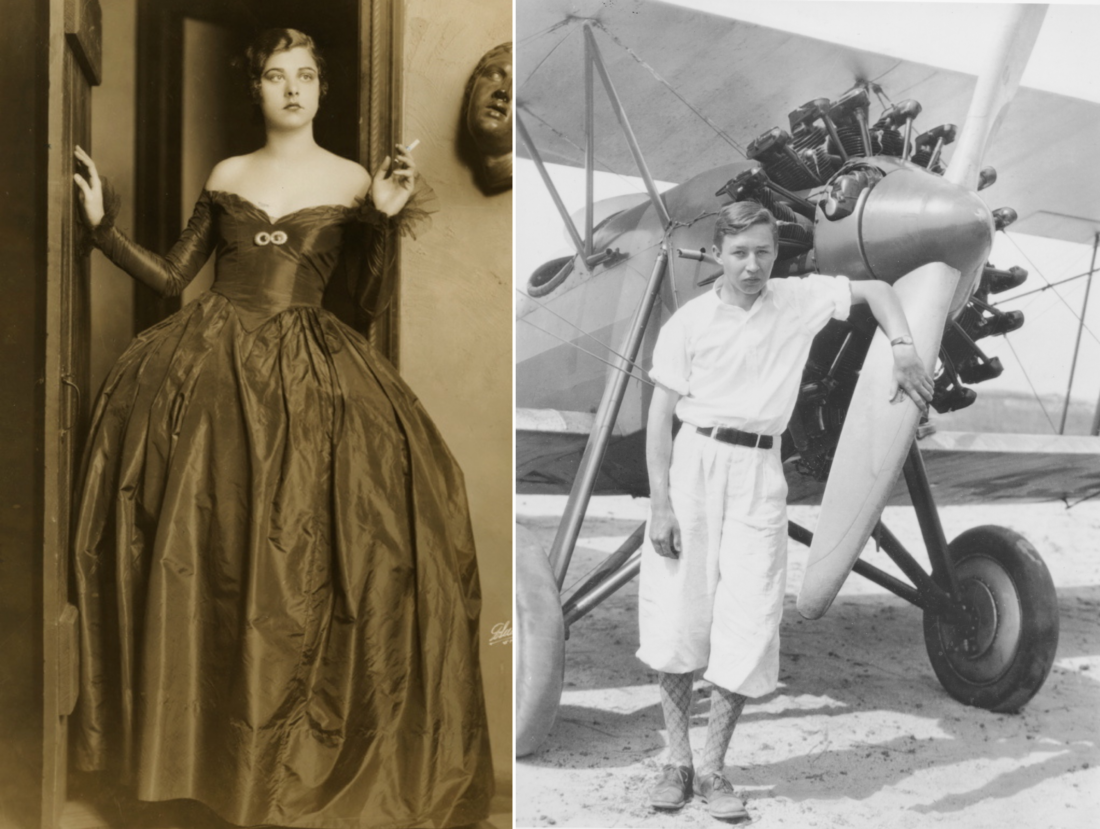

Shortly after midnight on July 6, 1932, Zachary “Smith” Reynolds, the youngest son of Winston-Salem’s illustrious Reynolds family and one of the heirs to the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco fortune, was shot in the head on the sleeping porch of his family’s home. Some believed it suicide—earlier in the night at a party, he was overheard saying he was going to “end it all.” Others thought it an accident—why would a twenty-year-old wealthy newlywed on the brink of an exhilarating aviation career take his own life?

His pregnant wife, the famous Broadway star Libby Holman, and his best friend, Ab Walker, would be indicted for his murder, although they maintained their innocence and charges were dropped before the case went to trial. To this day, the happenings of that night remain a mystery, and for more than ninety years, no one has discussed it in any official capacity—until now.

In the exhibition Smith & Libby: Two Rings, Seven Months, One Bullet (through December 31) the Reynolda House Museum of American Art, located in the family’s 1917 estate, delves into the lives of the story’s main players and the once-taboo night that changed the family forever. Although the death was long whispered about through Winston-Salem and beyond—even Hollywood found inspiration in the story, resulting in movies such as the 1933 film Sing Sinner Sing and 1956’s Written on the Wind—the Reynolds family and foundation has refrained from commenting. “In a way it’s been told by everybody except Reynolda,” says Phil Archer, the curator. “It’s not that these things were embargoed and we reached an anniversary and could suddenly open up the vaults or something. It’s more a matter of enough time passing for the descendants to express comfort about it being told. Why not tell the story frankly and transparently and show that these people were more than just the scandal of that moment?”

The exhibition sprawls across the Mary and Charlie Babcock Wing Gallery, an early 2000s addition next to the historic home where the incident took place. Archer interviewed dozens of relatives—descendants of Smith, Libby, lawyers, and even the nightwatchman on the scene—and scoured countless artifacts and documents. The resulting display walks visitors through Smith and Libby’s lives: Smith was a young pilot, a contemporary with Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart; Libby a freewheeling actress who had played leading roles for Oscar Hammerstein and whose love life made headlines. See the affidavit for their marriage alongside a picture from their honeymoon in Hong Kong and one of Libby’s dresses. “Smith was planning an around-the-world flight—he wanted to break the record for going all the way around the world. We found the globe he was using to plan his trip in a big warehouse out in the country and had it repaired,” Archer says. “We can’t bring people back to life, but we can make them feel much more alive by showing things that were closely related to them. These objects can be so eloquent.”

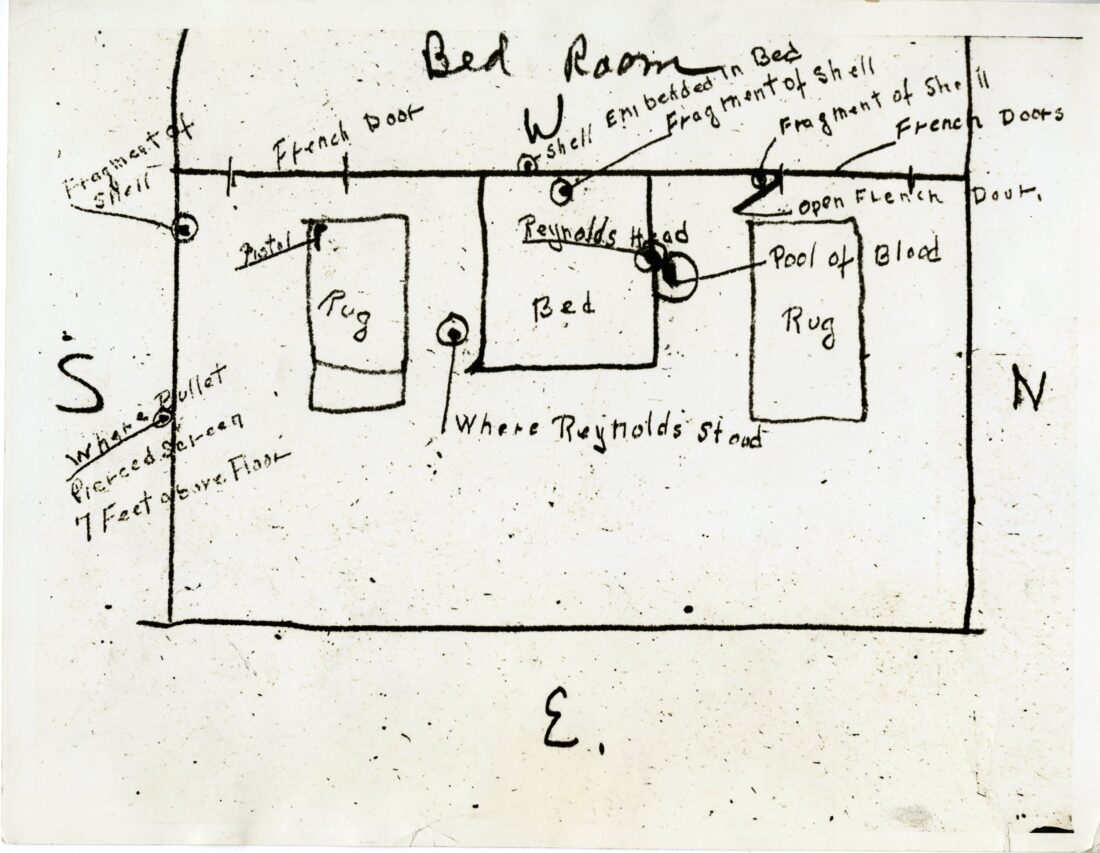

Then come artifacts connected to the fateful night and its aftermath, such as the wallet Smith had tossed to his friend after allegedly saying he was going to “end it all,” stuffed with fifty-nine business cards. “It’s the restaurants and nightclubs he went to, it’s the chorus girls that he called. His business interests, banking interests,” Archer says. “If you look at what the cards represent, it’s his entire life.” See the summons for Libby’s arrest, the sheriff’s drawings and notes, a fragment of the bullet that killed Smith, a ten-minute film by the Winston-Salem-based Out of Our Minds Animation Studios, and even a re-creation of the porch, drawn to scale on the gallery floor. (The actual porch, on the second story of the adjacent historic home, had been off limits to visitors until this exhibit opened.)

Naturally, news of the incident caught fire across the country. “It was in every small paper, looked at from every possible angle,” Archer says. “Love triangle angles were explored endlessly. A lot of papers were sold.” You can read some of those papers and watch newsreels in the exhibition too.

Libby and Ab were keen to go to trial to clear their names, but at the behest of the Reynolds family, the case was dropped. Trying to shed her new image as femme fatale, Libby would go on to study blues music, teaming up with the guitarist Josh White to create the country’s first integrated musical duo, before cementing herself as a civil rights activist, befriending Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King.

And even in death, Smith left a lasting influence beyond the headlines: His inheritance would create the first of the Reynolds Foundations and lead to the relocation of Wake Forest University to Winston-Salem.

But what actually happened that night? Archer has theories: “When you start comparing all the different stories, there’s so much that doesn’t add up,” he says. “It’s like Watergate: Whether there was a crime or not, there was certainly a cover-up.” Visit the exhibition before it closes on December 31 to draw your own conclusion.