According to the Chinese zodiac, 2023 was the year of the rabbit. According to just about everyone else, it was the year of Taylor Swift. She was Spotify’s global artist of the year, with 26.1 billion streams worldwide. She dropped two re-recordings of previous albums to reclaim the rights to her songs. She released a movie that grossed more than $250 million in box office sales. Her sixty-six Eras Tour shows attracted hundreds of thousands of fans to each city it visited, and added, by some estimates, $5.7 billion to the U.S. economy. Fittingly, she’s Time’s Person of the Year.

And while she’s an accomplished singer and perhaps an even more skillful performer and businesswoman, Swift’s storytelling is largely credited as the main cause for her astronomical stardom and remarkable longevity. Through her songwriting, Swift has an innate ability to capture her time and place in a way that touches others; ironically, the specificity of her lyrics makes them universal. That time she’s capturing, of course, is now. That place has changed over the years.

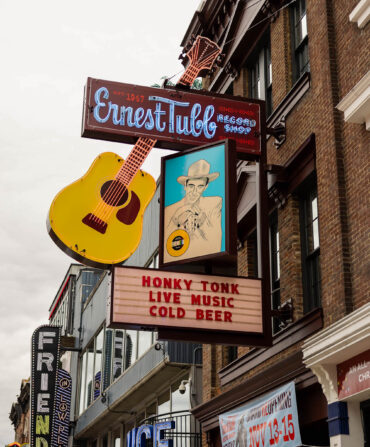

She grew up on a Christmas tree farm in Reading, Pennsylvania. (In her song “Seven,” she paints a picture of a child on a swing set, “high in the sky with Pennsylvania under me.”) But captivated by the seminal country music divas of the nineties—stars like Faith Hill, Shania Twain, and the Chicks—Swift convinced her family to relocate to Nashville when she was thirteen. “[My mom] would wait in the car as I scampered into record labels [on Music Row] one by one, handing my demo CD to the receptionists,” Swift told Time in a 2014 interview. “I remember thinking it was so odd and wonderful that all of these important record labels were all on one street, most of them in small buildings and old houses. I remember being charmed by how kind people were to strangers and newcomers like us.” She name-dropped Nashville’s Radnor Lake, the coffeeshop Fido, Hillsboro Village, and the Bluebird Cafe. “Now I have to stop because I sound like I am the president of the Nashville Tourism Board,” said the then-twenty-four-year-old. “Sorry, not sorry, I just love it here.”

She attended Hendersonville High School (sparking hits like “Fifteen,” “You Belong With Me,” and “Our Song”) until her career took off, and it was the city—and the region—that became the muse for the first few years of her career as she carved out a tentative niche in country music. She opened her first radio single, Tim McGraw (named, of course, after the Louisiana-born country icon), with the line: “He said the way my blue eyes shined put those Georgia stars to shame that night. I said, ‘That’s a lie.’”

When she moved in 2014, though, it was the buzz of New York City that began to populate her lyrics. “Welcome to New York, it’s been waiting for you,” she sings on her album 1989; “Dive bar on the East Side, where you at,” in Reputation’s “Delicate;” “Your heartbeat on the High Line, once in twenty lifetimes,” in Folklore’s “Cardigan.” She’s since sang of London, L.A., St. Tropez, St. Louis, Paris.

But throughout her global domination, Nashville has stuck with her. “And you know I love Springsteen, faded blue jeans, Tennessee whiskey,” she sings in her 2019 song “London Boy.” On her 2020 Folklore standout “Invisible String,” she references Nashville’s famous greenspace: “Green was the color of the grass where I used to read at Centennial Park.” In the 2020 documentary, Miss Americana, she puts it simply: “I really, really care about my home state.” Just this week, she donated one million dollars to tornado relief in Nashville.

If you’re merely listening to Swift for the specific, though, you’re missing her point. Like canonical literature and poetry (which many—including professors teaching Taylor Swift classes at such universities as Stanford, Rice, UT Austin, and Harvard—argue Swift is creating), she roots a story in a particular place and time in order to reveal something about the human condition. She sings of universal experiences: falling in and out of love, trying to fit in, reckoning with the passage of time, searching for peace in a tumultuous world, learning to accept yourself. Look around at one of her sold-out shows—whether this past year in Atlanta, Nashville, or Buenos Aires, or in 2024, when she’s set to make stops in nearly thirty cities including Tokyo, Warsaw, Vancouver, and New Orleans—and you’ll see fans of all ages, genders, and races singing, dancing, crying, and passing around friendship bracelets as they connect to her music. Taylor Swift’s magic lies in the fact that everyone can claim her.

Caroline Sanders Clements is the senior editor at Garden & Gun and oversees the magazine’s annual Made in the South Awards. Since joining G&G’s editorial team in 2017, the Athens, Georgia, native has written and edited stories about artists, architects, historians, musicians, tomato farmers, James Beard Award winners, and one mixed martial artist. She lives in North Charleston, South Carolina, with her husband, Sam, and dog, Bucket.