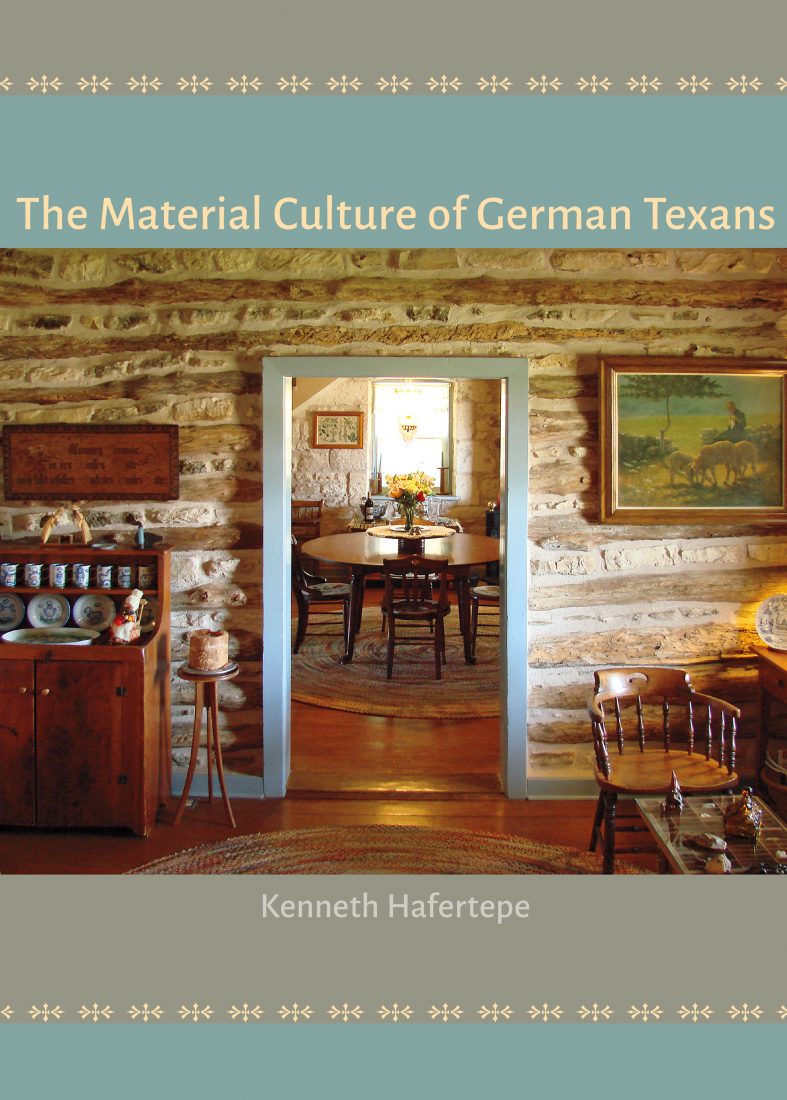

From the Wurstfest’s “Ten-Day Salute to Sausage” in New Braunfels to the bottles of Shiner Bock lining the bars in every central Texas dance hall, Germans have made their mark on the culture of the Lone Star State. A new book, The Material Culture of German Texans, considers the tastes and artistic influence of the early settlers whose homes, churches, and graveyards still dot the state’s landscape today.

Photo: Archival photo by Richard MacAllister

The Kiehne house in Fredericksburg (circa 1858) photographed in 1936.

The first German to set his sights on Texas was a man named Johann Friedrich Ernst, who sailed his family across the Atlantic and made his way to the Mexican province of Texas in 1831. He farmed tobacco, rolled cigars, and then wrote letters back to the motherland about the beauty and opportunity he found. A surge of German immigrants flooded the region to start businesses and cultivate the land throughout the mid-nineteenth century.

Newly independent from Mexico in 1836, Texas began forming an identity tinged with European and Hispanic elements that continued after its American statehood in 1846. By 1930, the U.S. Census Bureau noted that people born in Germany or whose parents were born there made up one of the largest ancestries in the state. Eventually, the largest European ethnic group in Texas was German.

Photo: Courtesy Witte Museum, San Antonio.

A painting of a mid-nineteenth century farmhouse near Frelsburg by Louis Hoppe.

Author Kenneth Hafertepe is chair of the department of museum studies at Baylor University in Waco, Texas. For this book, he spent more than a decade researching the history of Germans in Texas—visiting historic home sites and interviewing curators, archivists, historians, and descendants of pioneers.

Photo: Kenneth Hafertepe

German home in Gillespie County, built circa 1862.

Hafertepe examines buildings and furniture from rural, small town, and urban settings spanning East Texas and the Hill Country. In essays, interviews, sketches, and nearly 400 images, he reveals not only the tale of one immigrant group, but also the story of a nation coming of age.

Photo: Kenneth Hafertepe

A circa-1869 dogtrot log house at Stonewall Heritage Center.

“To understand the way in which German material culture became Texan and then American,” Hafertepe writes, “Is to understand the way in which these people refashioned themselves, their families, and their communities.”

Photo: Kenneth Hafertepe

Ceiling and over-mantel paintings at the Lewis-Wagner house in Winedale.

Photo: Kenneth Hafertepe

A four-poster bed by Johann Umland, c. 1860; a bed by Johann Peter Tatsch, c. 1856-65.

Photo: Kenneth Hafertepe

Interior of Krieger-Henke-Staudt house in Fredericksburg.

Photo: Kenneth Hafertepe

A detail in St. Mary’s Catholic Church (c. 1905) in High Hill; St. John’s Lutheran Church (1897) in Gillespie County.

Photo: Kenneth Hafertepe

The 1856 Kreische house dining room in Fayette County.