Food & Drink

25 Outstanding Restaurants Worth the Drive

Soak up a New Orleans grande dame, head to a Northwest Arkansas mezcaleria, or point the car toward a retro North Carolina steak house: These 25 eateries worth a trip will transport you

Photo: Emily Dorio

Restaurants used to be diversions. We traveled to Nashville to see big and blingy concerts at the Ryman or small and raucous shows at Robert’s. Music defined that destination. Just as Atlanta trips revolved around Braves games and High Museum exhibits. And Charleston visits demanded tours of house museums and knowledge of earthquake bolts and gib plates. (New Orleans was the exception that made clear the possibilities.)

That was then. Now we squeeze in art and games after lunch. Music comes after dinner. We travel to eat. And we recognize that the best path to knowing a town or a city often leads through a restaurant that reflects a place’s mores and appetites.

To make the point, let’s stick with Nashville, a fast-growing and sometimes bewildering city where three-story honky-tonks now line scooter-littered streets. That’s Mindless Nashville, a rickety state fair ride of a place that too often diverts attention from Mindful Nashville, a hub of creativity where new arrivals make art and commerce, a hive of beauty where the grace of working people disguises their grit.

Peninsula, which opened in 2017 in a new-build four-story, showcases the best of what modern Nashville yields. Spouses Craig Schoen and Yuriko Say handle beverages and service. They moved from Seattle with chef Jake Howell. All came with the belief that Nashville would get behind a restaurant that interprets the Iberian Peninsula, where Spanish, Portuguese, and Basque peoples and foods coexist. “The peninsula gives us room to move around and traditions to sample,” Howell says.

Playing to theme, scrolled iron chandeliers of seeming Spanish provenance hang in the airy space. Look close at the kitchen, though, and you see the lava lamp mounted at the pass, ectoplasm rising and falling in time to the rock that wraps the room in a downbeat chill. How does it all fit together? “Restaurants work better when they show a little mystery,” Howell says.

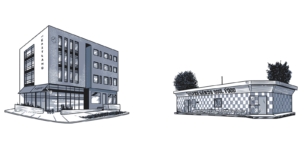

Illustration: Joel Kimmel

The Peninsula; Silver Sands.

Like novelists who skip transitions because they know readers are smart, Peninsula inspires diners to create their own narratives in the gaps between what the environment suggests and the menu promises. That shows in a Spanish-inspired tortilla, a mosaic of eggs and potatoes, served with a mound of bright orange trout roe and an alabaster dab of aioli. The dish marries Japanese precision to Iberian tradition and makes a subtle case that they complement. Ditto the steamed, smoked, and grilled eggplant, purple batons stacked in a shallow bowl like campfire logs. Around dishes like these, Nashville will gather for a long time.

Nashville is a looking glass. Tilt it one way and you see what the city is becoming. Look again to see what endures. To fully know Nashville, it’s important to know Silver Sands Cafe, the lunchtime soul bunker set in the shadow of downtown, a vestige of the past going hard in the paint in the present.

Sophia Vaughn runs the show, rose-colored dreads piled into a swirling corsage, a welcoming smile masking the aches that come with her work. Up by three in the morning to stir the grits and chop the greens, she leads a crew of six, including her daughter Antynish’e Kunbor, son Osato Kunbor, and stepson James Bowen. Moving past fry baskets overflowed with pork chops, weaving around a steam table stocked with neon-yellow squash and tomato-smothered meat loaf, they twist and turn through the kitchen like Alvin Ailey dancers, serving men in blue work shirts and women in fuchsia nurse scrubs.

“This would be easier if I just opened cans,” Vaughn says, cutting a regular a look that says she never will.

“You got pinto beans, don’t you?” he asks, already imagining the moment when he will drag a round of hot-water cornbread through the potlikker in which those beans bob.

Vaughn moves toward the register, where a woman with weary eyes waits to pick up a to-go box loaded with fried chicken and a double order of macaroni and cheese. They compare sleep schedules and back pains and talk grandchildren. Before the woman leaves, Vaughn will slip her a BC powder, a mindful gesture that says, I know who you are, and I know how hard you work. An act of care that says, Nashville is yours, and Nashville is mine, and together we’re going to soar.

Photo: Emily Dorio

Sophia Vaughn (center) with her stepson James Bowen and Fannie Johns in the kitchen at Silver Sands Cafe.

Silver Sands and Peninsula deliver on food and vibe. But like the twenty-five restaurants that follow, they do something more. Great restaurants are portals to knowing people and place. They are stages on which cooks and servers and patrons take star turns. They goad us when we’re joyful and fix us when we’re broken. Stitched together, these restaurants map what’s possible when we travel the South to gather at table in the summer and fall of 2022.

The Hummingbird Way

Mobile, Alabama

“Biscuit service” could sound about as stuffy as a sweater set or chintz drapes. But as with much of his menu, chef Jim Smith takes the traditional and turns it just so. Far from fussy, four buttermilk biscuits in a cast-iron skillet (no hidden doily) appear with the iconic duo of cane syrup and butter, along with a small dish of smoked sea salt for three-part harmony. An Alabama seafood devotee, Smith adds similar subtle dimensions to Gulf gets: a sash of sauce gribiche on fried soft-shell crab; a Vietnamese-inspired strawberry nuoc cham on a half-shell oyster; a crab cake sprinkled with a confetti of pickled oyster mushroom salad. Opened in 2020, the Hummingbird Way seems right at home in the idyllic Oakleigh Garden Historic District, an enclave of Greek Revivals, Queen Annes, and the like that could feel trapped in time if it weren’t for the community animating its porches and sidewalks, and, now, walking over to this former 1940s grocery store for dinner. —Hannah Hayes

North of Bourbon

Louisville, Kentucky

Southerners have long traveled to New Orleans to drink and frolic. Now Louisville is making a play for that business. What began with the Bourbon Trail has morphed into a galaxy of distilleries and bars and outfitters selling a brown-spirits lifestyle that connects these two river towns. North of Bourbon, which opened last December, gets the look right: Backlit bottles of Kentucky’s finest line a bar made of timbers salvaged from an old Maker’s Mark rickhouse. Chef Lawrence Weeks, who has Louisiana roots, gets the food right, too. “This is not a Creole-Cajun theme restaurant,” he says. Instead, Weeks borrows from New Orleans (sweet potato calas), expands to include Cajun Country (gumbo with a dollop of potato salad), and loops in the Mississippi Delta (vinegar-drenched salad greens à la Doe’s Eat Place). North of Bourbon makes a strong case that Louisville and New Orleans (and points in between) share a common palate—and a deep thirst. —John T. Edge

Charolais Steakhouse

Hickory, North Carolina

“I’ve got a big budget and a problem with vermouth,” James Vinson says when a guest asks if he makes a good Manhattan. Served in faceted glassware with the volume of a fishbowl, his cocktails set the tone at this 1969 steak house, made new in 2019 by local restaurateur Zackary Cranford’s team. The look is retro cool: Piebald cowhides wrap captain’s chair barstools. Lincoln pennies, set in Lucite, decorate the bar top. Wood beams crisscross the ceiling. In a glass-front cooler by the front door, bone-in rib eyes dry-age, taking on that ferrous tang. Prime rib glows in the light of a gooseneck heat lamp. Cranford stocks the salad trolley with forty-two ingredients, including a bottomless supply of Goldfish crackers. At Charolais, what’s old and true is not just new. Like that Manhattan, what’s old and true is now vogue. —JTE

Photo: Tim Robison

A tomahawk steak at Charolais.

The Grey

Savannah, Georgia

Chef Mashama Bailey and restaurateur John O. Morisano’s groundbreaking partnership changed Savannah. Since opening in 2014 in a onetime bus depot, the Grey has made a tangible impact on the city’s cultural fabric through its food, vision, and willingness to facilitate conversations about race and equity, and drawn numerous visitors eager to taste Bailey’s culinary ingenuity. Whether she’s using ingredients like ham hocks and collard greens for a heavenly terrine, or layering sweet potatoes over a rich blend of quinoa, buttermilk, and chowchow, her commitment to showcasing African American foodways and the value of Southern ingredients shines throughout. With the opening of the Grey’s charming low-key sister, the Grey Market, and now the duo’s expansion to Austin, Texas, her refined Southern fare is spreading its wings. “The fact that we strive to be a local restaurant in Savannah is also

our main goal here,” Morisano says. “Our relationship to the community is always what really matters.”—Kayla Stewart

Joel Kimmel

Photo: CHIA CHONG

Diners line the Grey Market’s lunch counter in Savannah.

Pantá

Memphis, Tennessee

“When we say Memphis is in Tennessee but Memphis is Memphis, that’s how Barcelona is to Spain. It’s its own special place,” explains David Quarles IV, the designer behind chef Kelly English’s Pantá, a Catalonian reinvention of the space that once held Restaurant Iris, his bistro that helped redefine the city’s dining scene when it opened in 2008. Pantá stems both from English’s time in Barcelona as a young cook, and a vision, shared with manager Aaron Ivory and chef de cuisine Patric Kee, that the historic cottage could reflect the new energy surfacing in Memphis. Ivory’s bar program focuses on gin and vermouth, and the menu on classic tapas, but with the volume turned up on playful presentation and big, bright hues that echo the space’s new look. “I wanted it to feel like Barcelona was picked up and put down in Midtown,” says Quarles, who referenced Gaudí architecture and the Costa Brava’s birds-of-paradise, alongside shades of blue, ivory, and gold, a nod to Grizzlies basketball pride. —HH

Photo: JUSTIN FOX BURKS

Pantá’s designer, David Quarles IV, at the restaurant.

Alpha Bakery & Deli

Houston, Texas

More than six square miles of triple-story strip malls, football-field-long markets, and parking lot labyrinths, Houston’s Chinatown enthralls as much as it daunts. And unlike neighborhoods of the same name on either coast, the district reflects the myriad cultures that make Houston one of the most diverse cities in the country. An ideal starting point: Alpha Bakery, tucked inside a hive within a hive. “Hong Kong City Mall is a snapshot of what this city is,” says the Houston chef Chris Shepherd, who often directs first-time visitors to Chinatown. “There’s a dim sum hall on one side and a Vietnamese crawfish joint on the other. In between, you’ll find an amazing pho shop, a build-your-own hot pot, boba tea shops, and dozens of mah-jongg players in the food court.” Across from a stereo shop, behind tables and shelves of plastic-wrapped snacks that look like a dazzling mosaic, Alpha makes its bánh mi to order, layering a range from barbecue pork to fried eggs to sardines with a bracing bouquet of cucumber, cilantro, carrots, and jalapeño tucked in house-made French bread. —HH

Commander’s Palace

New Orleans, Louisiana

The 1893 vintage restaurant appears amid the twisted oak canopy of the Garden District like a blue-and-white Victorian confection. Lunches go long and veer toward decadence, as fat squirrels scamper along the boughs while proprietors (and first cousins) Ti Martin and Lally Brennan work the maze of dining rooms, stoking the tempo with bright smiles and (danger! danger!) weekday twenty-five-cent martinis. Executive chef Meg Bickford—the first woman to lead the kitchen in this restaurant long run by Ti’s mother, the late Ella Brennan—broadcasts joy and pride and channels her inner Prudhomme. Witness her cast-iron-seared drum with field pea ragout. Fix on her roast quail, glazed with Grand Marnier and cognac, stuffed with smoked boudin. Bickford won this job in 2020 because she’s talented and fierce, not because she’s a woman. But doesn’t it seem right that a woman now leads the kitchen in the house that Ella Brennan built? —JTE

Photo: CHRIS GRANGER

Commander’s Palace executive chef Meg Bickford.

Cucina 24

Asheville, North Carolina

One of the great Southern Appalachian arts is storytelling, a tradition demonstrated nightly by chef Brian Canipelli. Since opening his downtown Asheville restaurant in 2008, Canipelli has made yearly trips to Italy, focusing each time on a different microregion. Then he comes home and cooks a tale of what he saw and tasted, using local farm ingredients. Chef Meherwan Irani, whose restaurant Chai Pani sits around the corner, admiringly refers to Canipelli’s resourcefulness as “ridiculous.” “It’s super easy to import the finest of everything,” Irani says. Instead, Canipelli insists on deriving deliciousness from the humble, serving a stunning mess of greens with white anchovy dip that he calls “odd plants,” and crafting an achingly delicate dish of fried fava bean shoots. Rome shows up on a plate of crisp-edged suckling pig lashed with chicories. Because when Canipelli’s not traveling, he’s head down on the line, eager to tell guests all about it. —Hanna Raskin

Photo: Courtesy of Cucina 24

Cucina 24’s wax bean fritto with cacio e pepe mayo.

Mama J’s

Richmond, Virginia

Visitors to Richmond can learn about the history of Jackson Ward, one of the first neighborhoods in the country to be known as “Black Wall Street,” at the Black History Museum or the Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, honoring the pioneering bank president. But they can taste the district’s living legacy of Black-owned businesses at Mama J’s, opened in 2009 by former deputy sheriff Velma “Mama J” Johnson and her oldest son, Lester, who wanted to help revitalize the historic neighborhood. There’s now almost always a wait for the restaurant’s crisp-skinned fried chicken and sweet corn muffins. Equally popular are the jumbo lump crab cakes, jolted awake by a heap of dry mustard and a nip of hot sauce. But Mama J’s hardly seems corporate: The Johnsons aim for it to feel like Grandma’s house, which is why the tender red velvet cakes pitch to one side. Nor are there photos of its many celebrity fans on the walls. Kevin Hart, Velma Johnson says, isn’t any more special to her than all the rest of her customers. —HR

Mosquito Supper Club

New Orleans, Louisiana

Melissa Martin isn’t much interested in arguments over what makes food truly Creole or Cajun. The Louisiana native and Mosquito Supper Club owner would rather talk about bayous. While Martin could tout her James Beard Award, or brag about how she sells out dinner tables each night, she’s determined to use her restaurant as a tool to fight climate change and environmental injustice, immersing diners in local seafood and striving toward more sustainable practices in her kitchen. As guests convene at a communal table in a nineteenth-century home in Uptown, they have the potential to dine with folks from as near as Tremé and as far as the United Kingdom. Meanwhile, Martin rolls out a menu built on the area’s bounty. Velma Marie’s oyster soup, an ode to her grandmother’s recipe; barbecued shrimp served with house ciabatta; and fresh crimson-colored crab speak Martin’s truth to power: The Louisiana coast is invaluable, and its gifts are worth fighting for. —KS

Fig

Charleston, South Carolina

Staggering numbers of eaters keen to scale gustatory heights visit Charleston every year, many of them eager to eat at FIG. They don’t all get there. Reservation slots for the celebrated restaurant, opened in 2003 by chef Mike Lata and Adam Nemirow and helmed for the past several years by the extraordinarily talented Jason Stanhope, are typically snapped up within minutes of being posted online. (Locals know their best bet is showing up early in the week at opening time to grab a bar seat or happily dining at 10:15 p.m. on a Wednesday.) But no matter where Charleston visitors end up eating, they’re likely to get a taste of the qualities that FIG in large part established as municipal hallmarks: the mastery of craft exemplified by its chicken liver pâté; the seasonal enthusiasm captured in the nine-vegetable salad, a remarkable cross of country know-how with citified technique; or the reverence for rice that informs a deceptively humble-looking bowl of Carolina Gold trimmed with banded rudderfish and benne. There is plenty here to consider. But in good Charleston fashion, FIG also knows how to bring the party: Just about every wine trend in the area, from grower Champagne to Georgian whites, tracks back to the restaurant, too. —HR

Photo: LINDSEY SHORTER

FIG’s steamed black sea bass on a curried carrot puree, with English peas, asparagus, and ramps.

Carnitas Lonja

San Antonio, Texas

True carnitas, the kind chef Alex Paredes grew up eating in his hometown of Morelia in Mexico’s Michoacán (where the dish originated), can’t be rushed, from knowing when to turn the pork sizzling in manteca (lard) to chopping the perfect mix of unctuous fat, crackly skin, and juicy lean. It’s clear Paredes knows it intuitively as his forearm tattoo of an octopus waves from the other end of the cleaver and a pile of pork perfection manifests on the cutting board at his south San Antonio outpost. His carnitas typically sell out by 2:00 p.m. His wild success allowed Paredes to open Fish Lonja, across the courtyard, where octopus makes a different appearance alongside fish and shrimp in the form of ceviche, tacos, and tostadas. —HH

Chez Fonfon

Birmingham, Alabama

Born in Cullman, Alabama, Frank Stitt joined a post–Julia Child generation of Americans who, after taking a hard look at the places that made them, fell harder for the foods and rhythms of France. In 1978, he moved to the small town of Solliès-Toucas in Provence, where he worked with Richard Olney, the aesthete who wrote the seminal cookbook Simple French Food. Inspired by Olney’s reverence for terroir, Stitt came home, winning an international reputation as this region’s foremost chef-interpreter of Southern farm goods and French techniques at his Highlands Bar & Grill. Until recently, diners considered Chez Fonfon, the French bistro he and his wife, Pardis, opened in 2000, a sibling restaurant. That changed with the pandemic, when Highlands went temporarily dormant and Fonfon’s back patio, framed by creeping-fig-draped walls, became one of the most coveted spaces in the South. Passing down a narrow hallway toward the patio, taking note of the Olney tribute menu on the wall, diners saw the Gallic promise that inspired a young Stitt. Eating mussels steamed in vermouth, digging garlic-butter-gilded escargots from a cast-iron crock, forking into trout amandine lavished with brown butter, they got the chance to truly see and taste Chez Fonfon. And a new-old Southern institution was born. —JTE

MARCH

Houston, Texas

The nation’s fourth-largest city is filled with culinary gems that reflect its ever-expanding community. At MARCH, which opened last year, chef and restaurant partner Felipe Riccio traverses the Mediterranean, the inspiration behind a tasting menu that aims to capture the breadth of that region’s cuisines. “We dive in regionally, then also historically and culturally,” Riccio says. “Food is so intertwined into everything that makes up a culture, so we really are able to pull from so many different places to start these different ideas in the kitchen.” A native of Mexico and a product of the dining communities within Europe and Houston, Riccio is currently focused on Southern France, as in the restaurant’s take on clapassade, a quintessential French dish of lamb heart, black olive, and salsify. The current menu is slated to remain through mid-August, signaling a new culinary journey is right around the corner. —KS

Photo: JODY HORTON

A woven tapestry wall and ceiling at MARCH.

Gypsy Sally’s

Leakey, Texas

Less than a mile from the Frio River, a sparkling, spring-fed waterway that cuts a cypress-and-juniper-lined path through the limestone bluffs of Frio Canyon, this purposeful dive showcases the same lazybones energy that a surfer canteen offers a Texas beach town. Gypsy Sally’s serves burgers slathered with crema and layered with pickled jalapeños, enchiladas stacked with red chile pork and fried eggs, skirt steaks crowned with peppers and onions, and ranch-water highballs made with tequila or sotol and floated with Topo Chico. Brand-new this summer, the restaurant is the brainchild of owner Morgan Weber, who made his rep in Houston at Coltivare and Eight Row Flint before moving nearby. He says Gypsy Sally’s aims to serve tourists and locals alike, who flock to the four-hundred-odd-person town of Leakey to float the Frio, stare at those limestone bluffs, and “day drink the sting out of summer sunburns.” —JTE

Photo: FREDRIK BRODÉN

A margarita and a Hamburguesa Tejano, with Yellowbird hot sauce, crema, and pickled onions and jalapeños, at Gypsy Sally’s.

Payne’s BBQ

Memphis, Tennessee

Stacked tall with bright mustard slaw, sitting in a glossy pool of mahogany sauce atop a cherry-and-white-checkered tablecloth, the chopped pork sandwich at Payne’s BBQ could easily be a Claes Oldenburg sculpture in all its colorful allure. Or maybe a William Eggleston photo. The snapshot contrasts with the restaurant’s concrete breeze-block exterior facing Memphis thoroughfare Lamar Avenue, away from the neon-lit stretches that typically draw visitors. The tile-floored interior with its smattering of four-tops doesn’t resemble the more popular image of memorabilia-strewn barbecue destinations, either. But you will find a sincere Memphis scene—construction workers, writers, nurses, and musicians at the window where Flora Payne and her son Ronald and daughter Candice chop and mop pork shoulders, ribs, and whole bolognas smoked over charcoal. And that sandwich, speared with a slender toothpick to keep its golden ratio of smoky, tart, and tangy together on the cloud-like bun. Some longtime customers invoke the spell “extra brown” for the coveted crispy parts of the chopped pork. Follow their lead. —HH

The chopped pork sandwich at Payne’s.

The Kitchen Table

Clermont, Kentucky

From the start, chef Brian Landry says, eighth-generation Beam family master distiller Freddie Noe was adamant that the restaurant at the bourbon company’s remade visitor complex—on the edge of Bernheim Forest, twenty-six scenic miles south of Louisville—serve pizza. Guests at the Kitchen Table can also order a rib-sticking triple-meat burgoo that would be the pride of any hunting camp, or spunky duck jalapeño poppers sweetened with cane syrup. In a lineup like that, pizza might sound like a sop to eaters accustomed to the same lunch at every tourist site. But Landry builds his pies on a foundation of the same yeast that for decades has invigorated every batch of Jim Beam, which he swears is what gives them their alluring tang and gravitas. His attention to detail shows throughout the trope-smashing restaurant, which is one reason it has even attracted enthusiastic after-church crowds since opening last fall. “We wanted everyone to feel welcome,” he says. “We actually make quite a few nonalcoholic cocktails.” —HR

Yeyo’s Mezcaleria & Taqueria

Rogers, Arkansas

Ten years ago, the Rios family began farming near the town of Little Flock, in the northwestern corner of Arkansas, home to three Fortune 500 companies, including Walmart. A Bentonville food truck came next, dishing posole worthy of the Mexican state of Michoacán, the first home of Don “Yeyo” Rios and sons Rafael, Roman, and Fernando. Then their first restaurant, Yeyo’s El Alma de Mexico, decorated with supersized Mexican wrestling masks, serving a killer cochinita pibil of achiote-roasted pork. Now the family has opened Yeyo’s Mezcaleria & Taqueria in nearby Rogers, where thanks to a booming economy that attracts new immigrants, more than 30 percent of the population is Hispanic. Here, Rafael, who leads the kitchen crew, serves tacos swaddled with mole and piles tortas with pork al pastor and chimichurri. His knowledge of mezcals is encyclopedic and infectious, but he’s not hidebound. Ask for a mezcal cocktail stirred with smoked rhubarb amaro, and taste the South that comes next. —JTE

Photo: MEREDITH BUTLER

Cocktails at Yeyo’s Mezcaleria & Taqueria.

Lynn’s Quality Oysters

Eastpoint, Florida

Once the source of 90 percent of Florida’s oysters, Apalachicola Bay is currently in the midst of a restoration project, with oyster harvesting prohibited through 2025. In the meantime, though, there are Gulf oysters on the half shell at Lynn C. Martina’s seafood shack, pressed up so close to the shore of the bay that the local seagulls’ feathers are perpetually ruffled about having to share the space. The restaurant is the outgrowth of a decades-old family business, once a shucking operation, and its fluency in seafood frying and beach-casual service hasn’t slipped during the sourcing sabbatical. Best enjoyed with a cold beer and a cup of peppery gumbo on the side porch, erected in 2018 after Hurricane Michael blew down the back patio, a tray demonstrates why a dozen raw at sunset here is a ritual worth upholding. When the local oysters come back, Martina’s customers will be ready. —HR

Photo: ALICIA OSBORNE

Lynn C. Martina on the porch at Lynn’s.

Warung Indonesian Halal Restaurant

Doraville, Georgia

It’s the sweet smell of kecap manis, the deeply colored soy sauce found across tables in Indonesia, coating a huge piece of flaky fish for the grilled dish ikan bakar. It’s the sound of the bakwan sayur, Indonesian vegetable fritters, sizzling as they’re submerged in hot oil. Or maybe it’s the bakso, a warm, comforting bowl of meatballs bobbing in a salted beef broth, surrounded by vegetables with a dash of fried onion. Whatever piques your fancy, Warung Indonesian Halal Restaurant, set in an unassuming strip mall in the immigrant-heavy Atlanta suburb of Doraville, takes diners on a culinary tour through one of the most diverse archipelagos in the world. The nasi goreng, a pride-and-joy Indonesian dish of fried rice topped with a fried egg, is not to be missed, but don’t overlook the nutty and saucy nasi pecel, a Javanese favorite. —KS

Photo: EMILY DORIO

From left: Nasi kuning with beef at Warung Indonesian; server Deni Mulyana.

Vestige

Ocean Springs, Mississippi

Ocean Springs has long been associated with the artist Walter Anderson, who painted the area’s flora and fauna in kaleidoscopic streaks of violet, chartreuse, and indigo. Those same colors now flood the ceramics holding chef Alex Perry’s work—many of them from Shearwater Pottery, founded by Anderson’s brother Peter. At Vestige, Perry combines the locally familiar with Japanese techniques (the restaurant’s co-owner Kumi Omori, Perry’s wife, hails from Northern Japan) for a tasting menu full of artful marvels—a smoked French Hermit oyster tartlet with yuzu and olive oil, or sliced pork with morels, fiddleheads, spruce, and koji butter. Perry has a story for every dish, too (often chronicled on Vestige’s Instagram account), like the turquoise bowl of crawfish tails and early-season tomatoes floating like buoys in a smoky jasmine-scented cream, inspired by a walk during the darker days of the pandemic. “I remembered the scent of jasmine emanating from the entangled trellises that lined our back roads,” he wrote of that time. “And how that efflorescent smell gave way to saline and smoke as I got closer toward the docks.” —HH

Virtue Restaurant & Bar

Chicago, Illinois

Is it possible that the best restaurant now interpreting the food of Black Southerners does business outside the South? Mark the ongoing impact of the Great Migration, when six million Black Southerners left for cities like Chicago, and what chef-owner Erick Williams does here in the Hyde Park neighborhood eats like destiny. His people came out of Mississippi. “When I was growing up, my parents warned me about going back home,” Williams says. So the chef returned through the kitchen door. In homage to the lives his people made here, he pickles smoked turkey and cooks it down with collards. Gizzards come on dirty rice, drenched in skillet gravy. He serves velvet-fleshed roast chicken with stewed rutabagas that taste dank and sweet. Night after night, he makes whole the northern and southern halves of the South. —JTE

Joel Kimmel

Deluca’s Pizza

Hot Springs, Arkansas

In the middle years of the last century, Hot Springs was a proto-Vegas, where poker games went all night and locals marked seasons by the horse-racing calendar. If you squint, a semblance of that Hot Springs remains. Especially if you squint into the smoke that rolls from the back of the kitchen at Deluca’s Pizza. Here, 725-degree brick ovens belch pilgrimage-worthy pies with nearly translucent crusts, topped with homemade Italian sausage or natural-casing pepperoni. Owner Anthony Valinoti grew up in Brooklyn. Since coming to Hot Springs by way of the actual Vegas (after studying in the pizza mecca of Naples, Italy), he’s worked to recapture the pizza of his youth—and the vibe that goes with it. Speakers blast Sticky Fingers–era Rolling Stones. Pinup portraits decorate the walls. Made from aged beef, his burgers are Brooklyn throwbacks, too. Homages to Peter Luger, the grand old steak house of Valinoti’s youth, they come with spicy pickle slices, tossed on plates like poker chips. —JTE

Vestal

Lafayette, Louisiana

“There’s so much soul in this town I don’t even know how to describe it,” says Katie Culbert, a Lafayette native and co-owner of Wild Child Wines. Culbert’s natural wine and conservas shop sits alongside a group of other new businesses downtown, where it’s not unusual to see young people with accordions and fiddles singing in Cajun French on the sidewalk. Another addition: chef Ryan Trahan’s ambitious Vestal. The shoebox space in shades of oystershell revolves around a fourteen-foot live hearth where his team fires enormous Gulf shrimp, whole fish, six different cuts of steak, and even beef cheeks for the lasagna’s Bolognese, while the oyster bar focuses on selections from farms in Louisiana and the Gulf. “There’s definitely a new wave of young and hungry creatives making big moves in this tiny town,” Culbert says. “The art, the music, the food. It’s all wild, yet still tethered to Cajun roots.” —HH

West Tampa Sandwich Shop

Tampa, Florida

The true measure of a café con leche is neither the strength of the espresso nor the heat of the milk. It’s the fervor of the discussions it inspires. Florida state representative Susan Valdés, who has been a regular at West Tampa Sandwich Shop for decades, credits the lively diner with making her a centrist. “To the left of me, the old-timers would sit, and to the right, the Democrats would sit,” she recalls. “You would hear the argument for the conservative side, and you’d say, ‘Makes sense. I get it.’” Then she’d hear the other side and decide, “Well, that makes sense too.” But there’s little dissension about the food at this neighborhood mainstay, where the vibrancy of the city’s Cuban culture goes on display every morning in the form of melty hot ham croquettes, fragrant mamey milkshakes, and Cuban sandwiches splashed with honey (to parry with the roast pork). Another point of agreement? The language used to express opinions, political or otherwise. “Spanglish!” Valdés says with a laugh. —HR

Photo: JAMES JACKMAN

A Cuban and café con leche at West Tampa Sandwich Shop.