Sporting

A Coastal Plain Quail Retreat

From hardscrabble roots, a onetime farmer creates his quail woods dreams in North Carolina, where good dogs and great friends make memories that stretch beyond the field

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

From left: Ricky Kelly, Bobby Harrelson, and the author around the fire post-hunt; Evidence of a good day.

They are brother and sister, two English setters as different as the day is long, and each is equally convinced there are quail on the ground.

Dexter worms through cinnamon fern turned auburn in the chill of fall. He takes a halting step and stops, trailing birds on the run. Ten feet away, Emma honors his point, her flanks quivering. Vaulting through open pinewoods, they are a jealous pair, eyeing each other with sidelong glances, desperate to be the first on point. But once one has a muzzle full of bird scent, the other bends to instinct and training, locking up tight to prevent bumping the birds.

They’re not the only pair quibbling in these quail woods. Looking on, Bobby Harrelson, who owns this spread of 850 acres about an hour northeast of Wilmington, North Carolina, and his friend, the North Carolina artist Bob Timberlake, fall to good-natured squabbling over whose turn it is to shoot. Each insists the other is at bat, and it will be this way for most of the morning: friendly ribbing over who should take the point, who should take the shot, and even who should claim a downed bird. Between them, they have nearly a century and a half of hunting experience. And more than fifty years of friendship.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Harrelson and longtime friend Bob Timberlake ease up to a point.

The birds, however, care little for this pinewoods tête-à-tête. The quail burst from a copse of baybushes and turkey oaks, the guns fly to shoulders, and the shots fly through the pines. A single bird tumbles out of the group, one wing down, sailing for the dark woods.

“Uh-oh,” Harrelson murmurs. “Looks like you just barely nicked that bird.”

Timberlake counters with a laugh. “You calling me a poor shot?”

Just then Dexter emerges from the brush, the bird in his mouth, with hardly a feather ruffled.

“Oh no, Mr. Timberlake,” Harrelson says, admiring the unmarked bird in a gloved hand. “I see what you’re doing. You’re shooting table grade only this morning!”

For the eighty-three-year-old Harrelson, it’s a moment, and a place, that seems to distill all the years that have come before. Like that bird in hand, his Genteel Plantation (which he named in the spirit of the legendary quail grounds across the South), with its restored 1867 farmhouse and piney woods and food plots and cypress-edged creek, is a harvest of decades of work, the sowing of goodwill, and the careful tending of wild woods.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

From left: A quail feather rests on the grass; A reproduction of an old hunting license on Harrelson’s vest.

For those who know him well, it’s no surprise that Harrelson would end up here, chasing quail across a farm he pulled out of disuse and disrepair. “Knowing land and knowing how to get the most out of land is his creative genius,” says his friend and attorney Joseph O. Taylor, of Wilmington. “And it doesn’t matter whether it’s land for a housing development or a retreat like Genteel, where he’s used every experience in his life to build such a memorable place.”

Born in the last days of 1936, in a small tenant farmer’s house outside Loris, South Carolina, Harrelson was raised by two sisters who adopted him (one he called his mother, the other sister) when he was six years old. They lived on a thirty-eight-acre farm, in a trim white house with neither electric power nor running water. There was little help in the fields. By the time he was eight, he plowed and harvested behind Red, the farm’s only mule. At fourteen, Harrelson landed a job driving a school bus, and squeezed in tobacco priming and planting sweet potatoes before and after his bus routes. He bought a used John Deere Model 40 tractor while in high school, but it was hardly a labor-saving device. “I worked the whole farm and went to school at the same time,” he recalls, “so that tractor just meant I could disk the fields at night after all the other work was done.”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

A Beretta Silver Pigeon ready for action.

He farmed the family ground full-time for four years after he graduated from high school, but it was too much for a single man to handle. Harrelson married, spent two years in the U.S. Army, and after his discharge, moved to Wilmington. He started a small construction business with a childhood friend. They’d fix doors. Replace screens. Work on a small house addition if the work came along.

But things didn’t stay small for long.

Over the last four decades, Harrelson’s companies have built thousands of homes, sold tens of thousands of lots, and created more than seventy residential and commercial developments in the region. He has shaped the landscape of southeastern North Carolina like few others, and he still goes to the office nearly five days a week. His latest venture is the conversion of the massive 67,000-square-foot New Hanover County jail to a social services complex named the Jo Ann Carter Harrelson Center, in honor of his late first wife. He has given more than a million dollars to the nonprofit center, which charges its two dozen helping organizations just enough rent to cover operating expenses.

So much of his career has been built around helping people attain their own dreams of living at the beach that it’s ironic how he’s gone back to a farm. “Now, I lived on the beach for seventeen years,” he explains. “The beach is nice, but it ain’t nice like this.”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

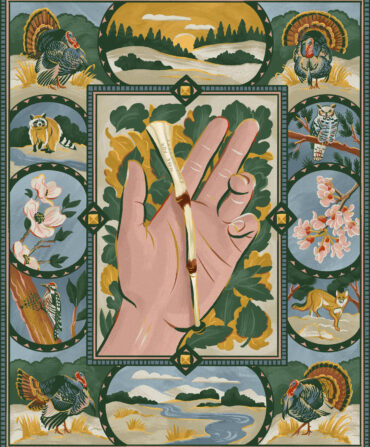

Kelly’s collection of turkey beards and vintage game loads.

When he first saw the farmhouse, in 1983, he could hardly see it. No one had lived on the spread for a decade or better. Brush choked the front yard, pecan trees barely visible in the thicket. The roofline of the house emerged from an enormous tangle of brambles and briars. When the chimneys came into view, poking out of the scrub—intact, hanging on, almost defiant—Harrelson knew in an instant: This is just what I want. The farm was small enough to handle, but large enough to match his dreams.

“Starting on the first day, we went to work on this place,” Harrelson says. “And I mean we worked.” With his friend, farm manager, and dog trainer Ricky Kelly, Harrelson pulled stumps, cleared paths, burned woods, planted food plots, and built a trophy bass pond that some visitors figure is as big a draw as the birds.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Morning in the pinewoods; Dexter locked up on birds.

The property is not a typical flat Coastal Plain landscape. The pinewoods are veined with dark creek bottoms, shrouded in soaring cypresses and tupelo gums. Bluffs along Moores Creek rise and fall fifteen feet, affording long views through tangled vernal timber flecked with trumpet creeper and shadbush blossoms. The land changes from the sandy soils deposited by the ancient seas that once covered the Coastal Plain to old loamy ground clad in mosses and muscadine vines.

In the upland forests, Harrelson has poured time and treasure into managing the woods for the benefit of bobwhite quail. The birds need thick cover for nesting, and open fields of seed-bearing plants for feeding, and brushy edges where chicks can glean insects, protected from predators. Sunny glades wink through the tall pines—feeding strips of milo, corn, and bicolor lespedeza, plus cover patches of dense burnished switchgrass. Each small plot of food or cover has been carefully planned, planted, and tended. Each pine trunk is blackened with fire from the frequent controlled burns that mimic the Coastal Plain’s natural fire regime, sweeping away tangled undergrowth and giving sunlight an easy path to the forest floor to nourish the woods with forage plants.

“We can’t make it into a wild bird hunt these days,” Harrelson says, “but we try to make the experience just like it would be by managing these forests to look like they did way back in the past. And one thing that hasn’t changed is this: We do our hunting out here like the old hunters did it: We walk.”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

From left: Kelly with a pair of bobwhites; Harrelson and Kelly in the field.

An invitation to a Genteel hunt is a cherished treat around the Wilmington region. Kelly keeps the farm’s stable of bird dogs—two pointers, five setters, and a black Labrador retriever—tuned up year-round. Hunts are scheduled at Genteel once or twice a week all season long, as Harrelson invites a friend or two to join him on the property and a few more for a country dinner to follow, often hosted with his wife, Estell. No big crowds. No big fuss. Nights are spent around a massive brick fire ring, where there is always bourbon and often oysters. “Those hours are just as important as what we do in the woods,” Harrelson insists. “We’re not on this earth to see how much money we can pile up, or how much land we can amass. I invest in people like I invest in land. I’m in it for the long haul.”

After the morning hunt, Harrelson and Timberlake relax on the farmhouse porch. The structure received its own dose of TLC while Harrelson and Kelly reshaped the pinewoods. The original home measured forty feet by forty feet and had three bedrooms downstairs and two upstairs, with a fireplace in nearly every bedroom. Harrelson built a large, roomy addition to the back of the house but maintained the historic scale of the front facade. The roof beams are made of solid forty-foot-long logs, a discovery Harrelson made when he tried to level the living room slightly by jacking up the floor, and the entire house tilted. “The house just wouldn’t bend,” he says, laughing, “so I said, well, let’s just keep it like it is.”

He was adamant about preserving the historic building materials. The outside walls are constructed of cypress, as durable as redwood and cantankerous to paint. Inside, log walls bear the telltale markings of an adze—proof of the handcrafted care that went into the home’s construction. Once, a few months after work commenced, Harrelson drove out to Genteel and found workers about to burn a large pile of hand-cut cypress shingles they’d stripped off the roof. “I almost had a fit,” he says. “I told them they better not put a match to anything that came from the house. I stored the shingles in a barn. I wanted to keep everything, because once it’s gone, it’s gone forever.”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Kelly in his taxidermy workshop at Genteel.

The house is decorated with personal mementos and seasoned with gifts from close friends. In the living room, anchored by the fireplace under massive exposed beams, the space is warmed with wood paneling. A soaring bookcase serves as a monument to the Southern sporting life. There are titles by Ernest Hemingway and Robert Ruark and George Bird Evans. An old wingbone turkey call reposes on a shelf. There are decoys carved by Ronnie Wade from the historic Swan Island Hunt Club of Currituck Sound, and photos of Harrelson holding brown trout in the North Carolina mountains. A Ward decoy pattern hangs on one wall. Harrelson once owned several of the famed Maryland carvers’ works, a collection he’s whittled down to a single pair of canvasbacks the Ward brothers carved in 1936, his birth year.

His own love of history has been a personal journey. He remembers when, years ago, Jo Ann wanted to purchase one of the stately historic homes on Front Street in Wilmington.

“Heck, I wanted a brick house,” Harrelson recalls. “I wanted something new, because I’d never had nothing but old.” But at Genteel, his love of the old was rekindled. These days, he says, “everything is built on the Timex plan. You don’t have anything repaired, you just buy a new one. That’s not the program we have here.”

Having grown up with so little, Harrelson seems keenly aware of the value in taking care of all that hard work and good fortune have placed in his stewardship. And that goes beyond pinewoods and food plots.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

The approach to the 1867 farmhouse; Harrelson on the hunt; dinner is almost ready.

Once, during the morning hunt, Harrelson and Timberlake get separated in the woods. Neither is as spry as he used to be, and Harrelson picks his way through saplings that slash at his brush pants, moving toward the sound of Kelly’s voice, calling to the dogs. He breaks out of the woods on a broom sedge field, the reeds laid low by winter’s cold and snow. Fifty yards away, Kelly steadies Dexter and waves Timberlake in for the rise. Harrelson watches his friend move toward the dog, sunlight slanting through the pines, the charred trunks dark among the tawny grasses like liver flecks in a bird dog’s coat.

“My gosh,” Harrelson murmurs. “My gosh, how pretty.”

In the distance, the quail flushes and Timberlake shoots twice. Harrelson is too far away to tell if either charge hit home. But that’s not where his mind wants to wander.

“I tell people all the time,” he says, “I can’t take this place with me, so I want to leave it better than I found it. Just like I want to leave my friends with a better relationship than when we found each other.”

Kelly takes a bird from Dexter’s jaws, but Harrelson has already turned away, moving through the woods he worked and dreamed and loved into existence.

“That right there is what I love,” he says. “If I couldn’t share this place, I’d shut it down. Wouldn’t stay open not one single day if it were all about me.”

This article appears in the October/November 2020 issue of Garden & Gun. Start your subscription here or give a gift subscription here.