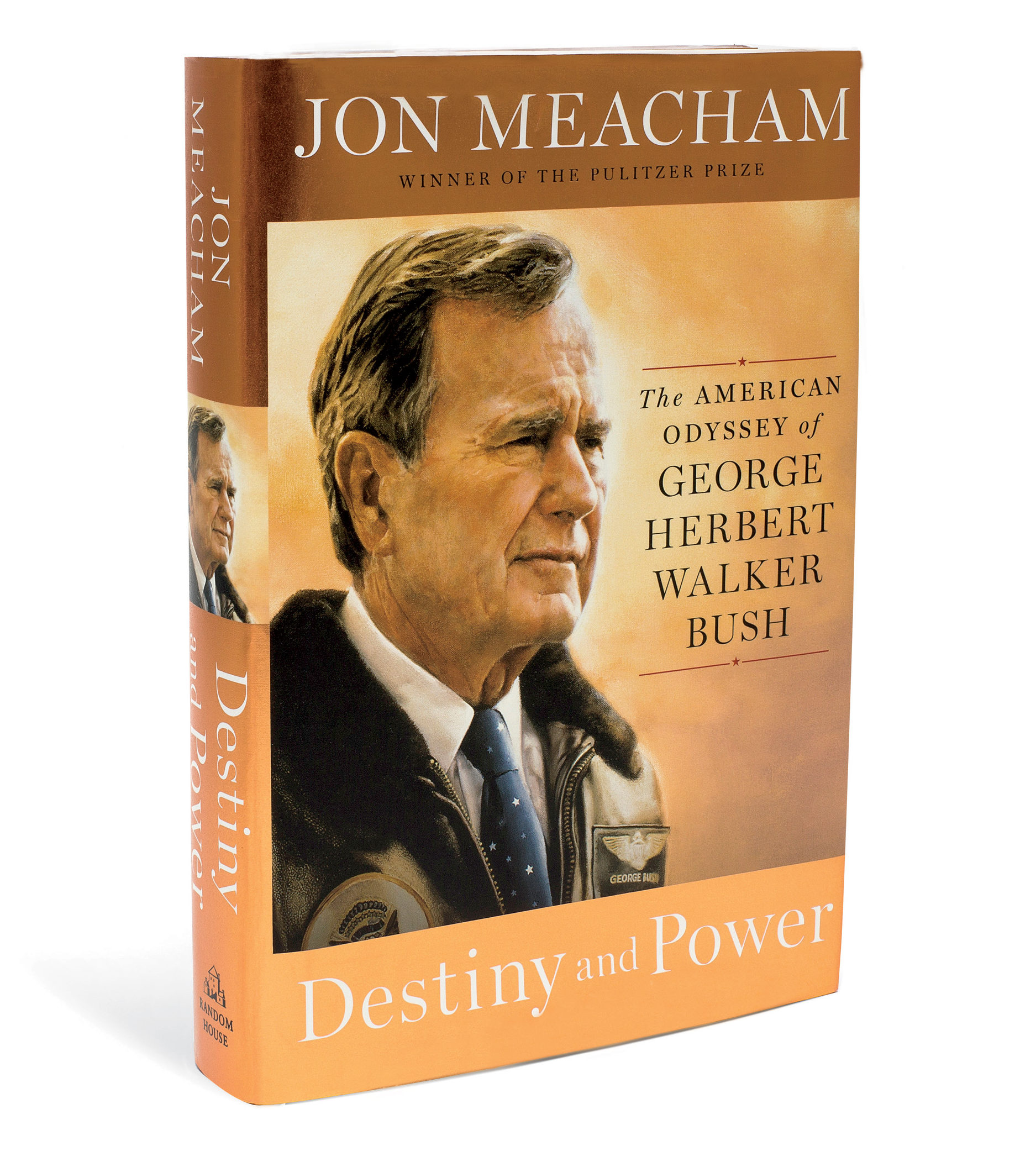

Arts & Culture

A Texas Education

In the summer of 1948, George H. W. Bush loaded his car in distant Connecticut and headed to the Lone Star State, a move that would shape the man and launch the future president’s political career

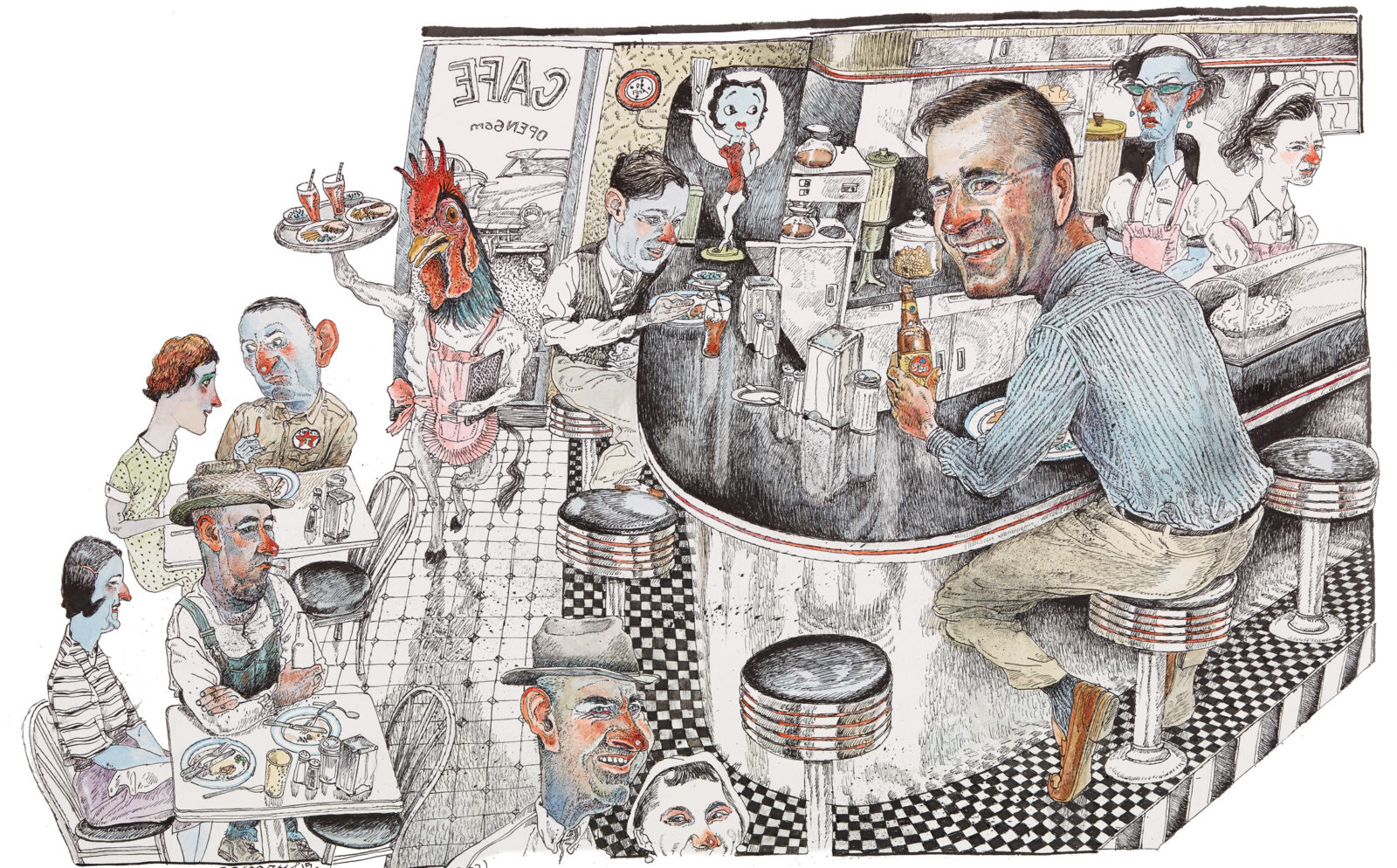

Illustration: Jack Unruh

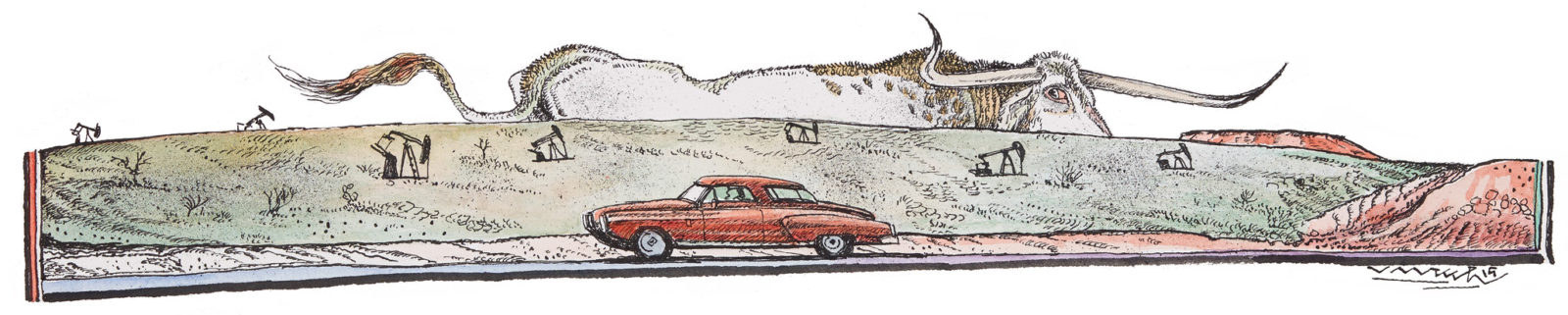

He wasn’t sure what he’d just ordered. It was the summer of 1948, and George Herbert Walker Bush—his childhood nickname of “Poppy” had been a casualty of World War II—was driving south and west from Connecticut. The son of an investment banker, Bush had grown up on Grove Lane in Greenwich, prepped at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, gone to war in the Pacific, and returned to finish college at Yale in two and a half years. Now he was behind the wheel of a red Studebaker—a graduation gift from his parents—driving through Texas, heading for a job in Odessa. Stopping for lunch outside Abilene, Bush walked into a wooden-frame restaurant.

The signs outside advertised regional beers—Lone Star, Jax, Pearl, and Dixie. He asked for a Lone Star or a Pearl—no time like the present to get into the local ways—and, looking over the menu, Bush decided to go all in. “Chicken-fried steak,” he said to the waitress. Would it turn out to be a steak fried like a chicken, or a chicken fried like a steak, Bush wondered. Ten minutes later came a steak covered in what he thought was “thick chicken-type gravy.” Between the midday beer and the steak and the gravy, Bush found the last two-hundred-odd-mile push west to Odessa a sleepy one. But he made it, passing derrick after derrick along the otherwise barren landscape, parking the Studebaker next to the small tin-roofed Ideco store, which sold parts for oil drilling. That was to be his base as he learned the oil business from the ground up.

And so began an essential chapter in the American odyssey of George H. W. Bush, a child of privilege who would rise to become the forty-first president of the United States. The son of one generation’s ruling class, he was the father of another: In the fullness of time he would share a distinction with John Adams as the only two American presidents to see their sons reach the pinnacle of power.

Without the move to Texas nearly seven decades ago, however, it is difficult to imagine that either Bush—George Herbert Walker or George Walker—would have become president. Though he could not know it at the time, the senior Bush was moving not only to where the money was (in Texas oil) but also to where the power was going to be (in the increasingly conservative—and ultimately Republican) Sun Belt. To understand why the Bush family is even now a formidable force in the life of the nation, we have to pick up H. W.’s trail in the Texas of the forties and fifties. He’d struck out for Texas—his wife, Barbara, whom he’d married in 1945, and their son Georgie, born in 1946, flew to meet him—because he couldn’t see himself doing the conventional thing by going to Wall Street. Offered jobs in finance, Bush demurred. “It just wasn’t different enough,” Bush recalled in an interview decades later. All Bush really knew about Texas had come from a brief wartime stint in Corpus Christi, and, he admitted, from Randolph Scott movies. But Texas meant adventure.

Jack Unruh

Within a week of arriving in Odessa, Bush rented half of a duplex on unpaved East Seventh Street and sent for Barbara and the baby. The apartments were connected by a common bathroom. On Chapel and Edwards Streets in New Haven, the Bushes had shared a bath before, but the similarities between Yale and Odessa ended there, as Barbara discovered when she and Georgie got off the plane from New York after a twelve-hour trip. They were stepping into what she called “a whole new and very hot world.”

Back home in Rye, New York, Barbara’s mother, Pauline Pierce, was puzzled by the whole business. “Who had ever heard of Odessa, Texas?” Barbara wrote of Mrs. Pierce’s reaction to the move. “She sent me cold cream, soap, and other items she assumed were available only in civilized parts of the country. She did not put Odessa in that category.” The Bushes’ fellow renters next door, a thirty-eight-year-old mother and her twenty-year-old daughter, were prostitutes whose callers often locked the Bushes out of the bathroom.

Bush shot doves with pals from Ideco, who taught him how to clean the birds, freeze them, and then, in due course, fry them up. There were football games and occasional dinners with old Yale friends in Midland or a drive-in movie (the Bushes saw The Egg and I over Labor Day weekend 1948). Sundays were spent going to church, napping, and then taking Georgie to the playground. Though both Bushes were cheerfully adaptable, George worried about Barbara. “She is something, Mum, the way she never ever complains or even suggests that she would prefer to be elsewhere,” he wrote home to his mother, Dorothy Walker Bush, in October 1948. “She is happy, I know, but anyone would like to be around her own friends, be able to take at least a passing interest in clothes, parties etc. She gets absolutely none of this. It is different for me, I have my job all day long with new things happening, but she is here in this small apt.”

Barbara got a library card and loved suggestions for books to read. Her mother-in-law sent her a 1,500-page Civil War novel, House Divided, which she devoured. The young couple read Time and Life each week and got the Wall Street Journal and the Odessa American, which came daily except Saturdays. By Christmas, Bush had moved the family from East Seventh to East Seventeenth, where they would have their own bathroom. On Christmas Eve, Bush was assigned bartending duties at the Ideco company party. The task did not require much expertise: Most of the crowd drank straight whiskey or, if they were taking it easy, whiskey with a bit of water. A martini man in New Haven—Bush tended to have one or two drinks and that was it—he got into the spirit of the place and of the season that afternoon. A great many amber-colored drinks later, Bush was poured onto the flatbed of the company pickup truck; his colleagues dropped him off in the yard in front of the new house. “That, at least, was the way Barbara told the story of our first Christmas Eve in Texas,” Bush recalled. He admitted his memories of the day were, at best, fuzzy.

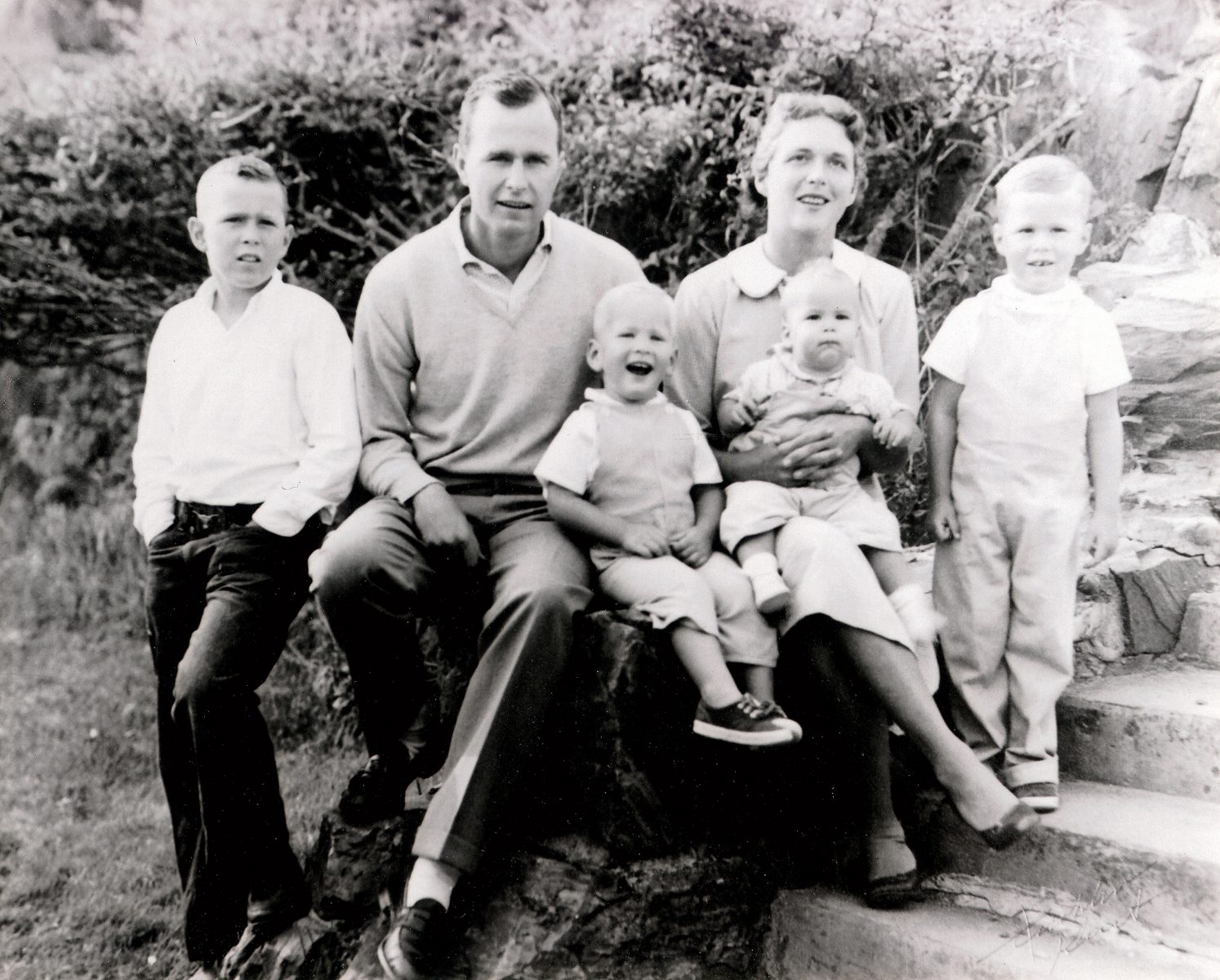

Courtesy George Bush Presidential Library and Museum

Texans at Heart

George H. W. Bush with his family (from left), George W., Neil, Barbara, Marvin, and Jeb, in 1957.

Bush was a quiet fretter. “The job continues in an interesting fashion, although I am selling or supposed to be, and am frankly very sad at it,” he wrote a friend. “I drive around to rigs and small company offices, and so far have sold nothing.” Yet he knew he was in the right place. “This West Texas is a fabulous place…. Fortunes can be made in the land end of the oil business, and of course can be lost…. If a man could go in and get just a few acres of land which later turned out to be good he would be fixed for life.” Money, however, was not the only thing driving him. In January 1949, Bush—then twenty-four years old—wrote a friend, “I have in the back of my mind a desire to be in politics, or at least the desire to do something of service to this country.”

The Bushes soon moved to Midland, where they lived on Easter Egg Row with other young families. (The houses were painted in pastels.) The 1950s brought both tragedy and joy as the Bushes built their lives in Texas. They lost a daughter, Robin, to leukemia, but soldiered on, becoming an essential part of the fabric of life in Midland. As Bush grew more interested in offshore drilling, the family moved to Houston, where, in 1962, he became the Harris County Republican Committee chairman.

Always a man in a hurry—World War II and the loss of Robin had taught him that life was “unpredictable and fragile”—Bush unsuccessfully ran for the U.S. Senate in 1964. He won a House seat in Houston in 1966, then lost another Senate race, this one to Lloyd Bentsen, in 1970.

Before the 1970 campaign, Bush had paid a call on former president Lyndon Johnson to ask for advice. Bush had a safe House seat; was the Senate worth the risk? “Son,” Johnson said, “I’ve served in the House. And I’ve been privileged to serve in the Senate, too. And they’re both good places to serve. So I wouldn’t begin to advise you what to do, except to say this: that the difference between being a member of the Senate and a member of the House is the difference between chicken salad and chicken shit.” LBJ paused. “Do I make my point?” He did.

For the next twenty-two years Bush would hold a series of jobs that kept him on the go: ambassador to the United Nations, chairman of the Republican National Committee, envoy to China, director of the CIA, vice president, and finally president.

Through it all he always came home to Texas. He was mocked for professing a love of pork rinds and Dr Pepper, but he actually liked pork rinds and Dr Pepper. Critics thought he affected a fondness for country music (Crystal Gayle, Dolly Parton, the Gatlin Brothers, and the Oak Ridge Boys were favorites), but Bush truly loved it. “It’s a great mix of music, lyrics, barrooms, Mother, the flag and good-looking large women,” Bush told his diary. “There is something earthy and strong about it all.”

When he lost his bid for a second term as president, Bush moved back to Houston, built his presidential library in College Station, and made Texas what it had been for more than four decades: home. He will be buried in a grove of trees near his library beneath an iron seal of the presidency of the United States—at rest in the state that taught him about the dreams of a big, complicated nation that once entrusted him with ultimate authority, and the state that introduced him to chicken-fried steak.

Garden & Gun has affiliate partnerships and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a product. All products are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.