Travel

A Tour of Bermuda’s Wild Side

An Appalachian outdoorswoman lets her feet, mind, and taste buds wander Bermuda, where art and nature promise a sort of redemption

Photo: Meredith Andrews

From left: Limestone formations frame a blue view on Cooper’s Island in Bermuda; coconuts at Cooper’s Island.

The rest of Bermuda is asleep, but we are up with the birds and the stars. My guide, Weldon Wade, and I have trekked to the island’s largest wildlife sanctuary to watch the sun rise over Spittal Pond along the Atlantic Ocean. As we fumble our way toward the water, we find ourselves caught in that stretch of darkness before dawn: The sky has yet to lighten to lavender, which means we can only hear the high-pitched calls of the killdeer, not see the birds themselves. It will be an hour, maybe more, before the sun reveals their hiding places, so I focus on the staccato clicking coming from a ruddy turnstone as I try to find my footing.

Photo: Meredith Andrews

Diver Weldon Wade on the beach at Southlands.

Wade is a Bermudian diver and the founder of the conservation organization Guardians of the Reef. When he isn’t free diving to hunt invasive lionfish or leading cleanups to remove litter from the ocean, he can be found in preserves like this one—spots that make Bermuda a bird-watcher’s paradise. White-eyed vireos, starlings, and sparrows all nest here, and rarer species like white-tailed tropic birds, known locally as longtails, stop through annually and help mark the change in seasons.

The chatter coming from whimbrels sounds like something between a whine and a whistle, as if they feel just as skeptical about being awake as I do. We hear curlew-curlee coming from a thicket of buttonwood and bay grape trees, its speaker unfamiliar. I brace for the onslaught of mosquitoes that always materialize to feast upon me. They never come. They won’t, Wade explains. Spittal Pond is brackish. No standing fresh water, no mosquitoes. This truly is paradise. By the time we make it to the seaside’s edge, the sky is the color of a ripe plum, but soon all will go lilac, heralding light.

Photo: Meredith Andrews

Stalactites at Crystal Cave.

I flew from Atlanta to Bermuda two days before. I am afraid of flying and always have been. Usually, I would take something to sleep away my anxiety, but boarding the plane was the closest I’d felt to freedom in some months and I made myself stay awake, saying hello to the wider world from my airplane window. For just a few minutes, the sea and the sky are the same color—one punctuated by coral, the other dotted with clouds, and I exist in this liminal space. I understand what I have left behind but do not know much about what I am moving toward.

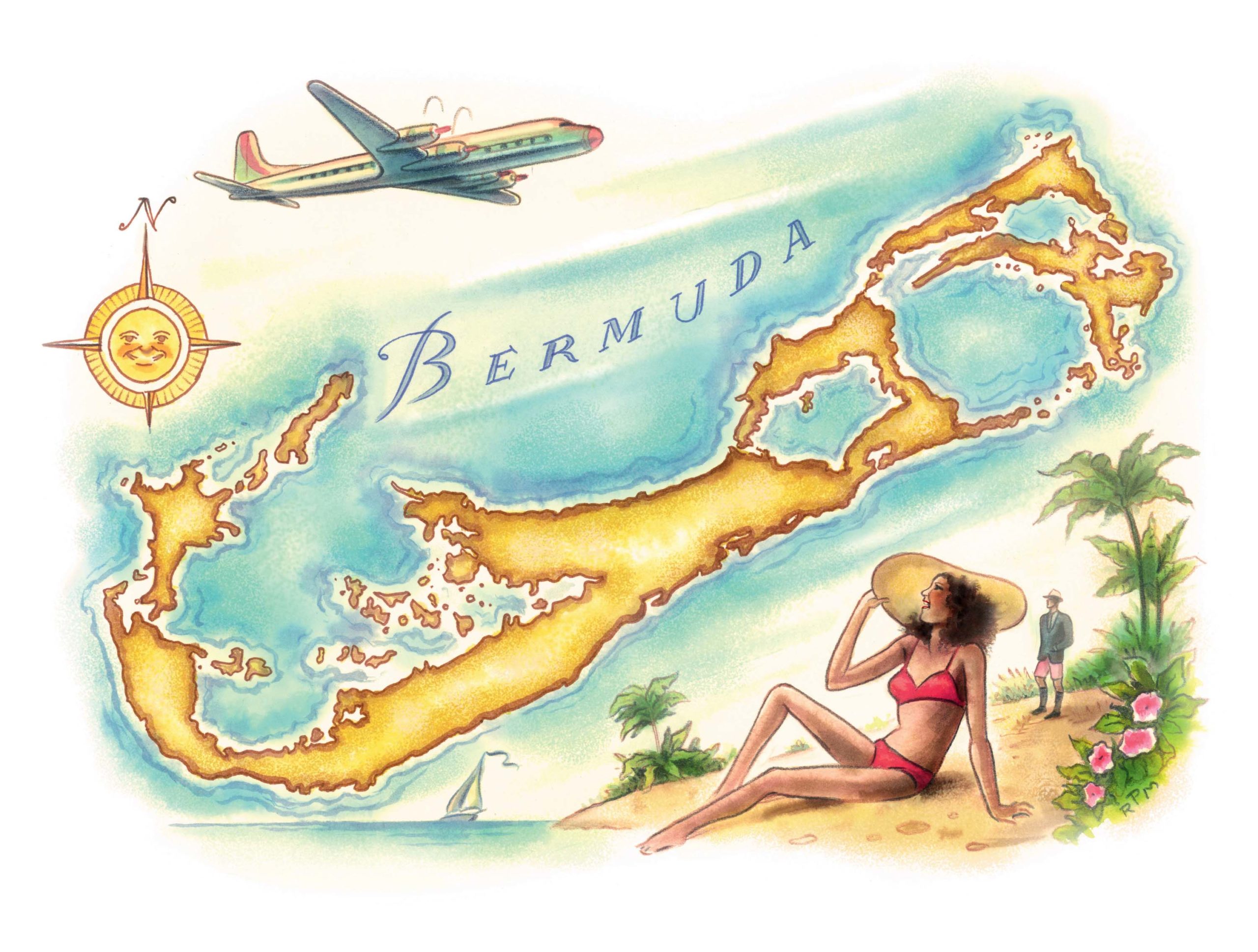

The word island might take you far away, to a land of shipwrecks, pirates, and treasure. Or perhaps to endless beaches, spectacular sunsets, and unlimited cocktails served in coconuts. The truth about Bermuda lies somewhere in between. A British territory, but beyond the occasional formality, not British really. Colorful like the Caribbean, but too far north to count. The closest landmass is North Carolina, less than seven hundred miles west. Not far from the American South, but still, not Southern.

Photo: Meredith Andrews

A traditional Bermudian roofline.

Spanish mariner Juan de Bermúdez first documented the archipelago in the early 1500s, and Bermuda long served as a stopover where shipwrecked crews made repairs and foraged for food. Sailors called it the Devil’s Isle for its treacherous reefs and because of the sounds created by nocturnal cahow birds and wild hogs chortling from the shore. Five hundred years later, the place that once inhabited early explorers’ nightmares is now a twenty-first-century visitor’s daydream.

I thought about all of this as I watched the color of the sea shift from sapphire to azure. I felt far away from the Appalachian foothills where I am from, where the hard freezes had started and there was nothing left to bloom. In 2020, I lost my grandmother and said a heartrending farewell to my family’s farm when it sold at auction. With the stroke of a pen, I had lost my connection to my homeplace, to the hundreds of flowers my grandmother tended for decades and the magnificent view of the stars from my father’s porch. In a year full of restrictions and modifications, my relationship to the things that routinely buoyed me felt severed too. The tragedies I felt most keenly were my own, but the world’s losses, upended traditions, and stresses compounded them. As the year clipped to a close, I realized I was numb.

Meredith Andrews

Perhaps in Bermuda, with the thriving viridescent flora of the subtropics unblunted by frost, and its pink sand beaches, sherbet-colored homes, and fourteen endemic plant species to awaken my curiosity, I could remember how to feel. Pandemic protocols make the island a relatively safe choice, and after taking the required COVID test prior to departure, and another one upon arrival, I was desperate to put my body in the Atlantic and talk to it, praying it could carry my worries away on its waves. I had six days here to search for myself and fortify her, before boarding a plane back to what was sure to be a long dark winter. To find some wonder again. And so I promised myself I would wander, that I would seek out what most fuels my soul: nature and art.

The latter is everywhere, just one of the ways the isle stuns me. The street art in the capital city of Hamilton, with a mural on seemingly every block, rivals that of cities like Austin and Nashville. The hotel for the first half of my stay, Hamilton Princess & Beach Club, doubles as an art museum with some three hundred pieces among its holdings. Jeff Koons, Takashi Murakami, and Andy Warhol works dot the hallways and accent the lobby. My room’s balcony, looking out to Hamilton Harbour, also has a view of Yayoi Kusama’s Pumpkin in the open-air courtyard. Kusama’s work speaks to me, and every year I make a point to see one of her exhibitions, sometimes waiting hours in the cold. Staring at her bronze sculpture, I realize I haven’t been to a museum all year. This is the most art I’ve seen in months. I smile.

The island has long been a haven for artists. Georgia O’Keeffe came here in the 1930s to treat her depression, and some of her pieces hang in the Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art. Tucked away inside Bermuda’s botanical garden, the space houses more than 1,500 works. A sculpture paying homage to John Lennon, another island visitor, stands in front of the building.

After exploring the art museum, I meander through the garden on market day and delight in the island’s produce, a great point of pride. Bermuda’s bananas are tiny compared with the Cavendish cultivar in stores back home. Tasting a Bermuda banana, I have the revelation that my revulsion for bananas probably comes from my taste buds recognizing underripe ones. These are ready to eat, and the rest of my fruit disappears from my bag as I walk around the garden’s grounds, documenting every color hibiscus I come across—opal, cerise, and a new-to-me two-toned variety with golden petals and a vermilion center.

Photo: Meredith Andrews

The ruins of an unfinished 1800s stone church in St. George’s.

Every place I go over the next few days, I learn and unlearn. When people think of this island, they might envision sailing and Bermuda shorts, but centuries of history have happened here. Kristin White, one of Bermuda’s cultural ambassadors, offers walking and cycling tours through her bookshop, Long Story Short, and her route through the town of St. George’s highlights several of the island’s Black changemakers and survivors. Mary Prince, for instance, whose autobiography about the cruelties of slavery galvanized the country’s abolitionist movement. Her ability to recount the painful parts of her past changed the course of the island. In Hamilton sits a statue of another enslaved woman, Sally Bassett, who was burned alive for poisoning her owners. Folklore says that Bermudiana, the country’s national flower, grew among her ashes. The plant still blooms here, the flower’s distinctive purple petals and bright yellow center never allowing people to forget. I marvel at the way Bermudians have turned a story about another’s suffering into something they could understand, and along the way have found something enduring in it.

Photo: Meredith Andrews

Travel guide Shuntelle Paynter at Penno’s Wharf in St. George’s.

There are smaller revelations and simple pleasures, too: the scent and sound of allspice leaves as they click together during a westerly breeze; how my aversion to lobster melts away when I eat one in season, paired with the small but sweet Bermudian peaches at Huckleberry Restaurant. In Fort Hamilton’s fern garden, I wander down hidden passages, vacillating between green and more green, and leave exuberant, the smell of chlorophyll still clinging to my skirt. One night at the glamorous Rosewood resort at Tucker’s Point, I have the pool to myself for a starlit swim. I pick out the constellations Draco and Cepheus and think of all the time I’ve spent looking up at the sky since I was a child, hoping to understand my place in the universe.

My itinerary is filled with these kinds of quiet moments of beauty. But adventure calls, too.

“I don’t think I can do this,” I utter through clenched teeth, my hands gripping the handlebars of a cherry-red cruiser. I am in St. George’s with Shuntelle Paynter of the tour company A Journey to Telle, heading off on a two-hour e-bike excursion to explore the caves in Walsingham Nature Reserve, known to locals as Tom Moore’s Jungle.

I am a competent cyclist, but only barely, and dark wild spaces make me claustrophobic. Still, I strap on my helmet, say the Lord’s Prayer (I am sure God was as shocked to hear from me as I was to be calling on him), and push off. As we dodge vehicular traffic, my knuckles turn the color of a Bermudian roof. But I try to take in the landscape, too—I’ll never get this perspective from the back of a taxi, one of the primary modes of transportation here, since visitors aren’t allowed to rent cars.

When we arrive at the reserve, I feel almost giddy, relieved I didn’t wind up as someone’s hood ornament and intoxicated by the scene before me. In the bay, parrotfish, with their Day-Glo lips, wind their way through seagrass beds in search of algae. We leave our things at the entrance and hike into the forest to a cave wide enough to fit inside. I descend into this subterranean world, inching forward until my eyes adjust to the darkness, heartbeat pounding in my ears. A crystal-clear lake surrounds me on three sides. Thick winter-white stalactites, millions of years in the making, hang from the ceiling, defying gravity.

Photo: Meredith Andrews

Fort Hamilton overlooks a lush garden of palms and ferns.

On the way back to our bikes, I spot a single flower in the grass: a golden-yellow rain lily. I have only seen this plant once before: White ones grew in my grandmother’s front yard. The last time I saw my homeplace before it became somebody else’s, I plucked one, pressing the bloom between two pages of a book. I do not dare pick this canary-colored one, knowing it would not survive the bicycle ride back, or the rest of my adventures. I take a picture to remember the moment, the sign.

Yellow is the color of sunshine and all the good things associated with it: warmth, optimism, creativity. Yellow, to me, represents self-confidence and by extension happiness. As we cycle back across the causeway, I ask myself, Am I happy? I think about the smile I can’t seem to get rid of, the ruddiness in my cheeks, my audacity in the cave.

Maybe, just for now, I am.

Photo: Meredith Andrews

On the fifth day, I meet Doreen Williams-James out on Cooper’s Island, a decommissioned military base, to take part in her Wild Herbs N Plants tour. For years she’s led treks out into the lesser reaches of the islands to talk about the edible plants that grow there. She teaches me how she lives off the land, making baked goods, salads, soups, and teas from things she forages.

“The island can provide everything you need to survive,” she tells me in a gentle, lilting voice. “When we think of hurricanes, we think of destruction, but the plants—they come back. Mother Nature will take care of us.” She indicates where the wild oranges will be when the time is right, and what to look for during loquat season. She picks up some sea purslane and hands a piece to me. I put the aqua pearl in my mouth, and when it pops, there’s the sensation of eating a salty cucumber.

Photo: Meredith Andrews

Doreen Williams-James at Spittal Pond.

I snack and learn—peppery nasturtiums, jewel-colored prickly pear fruit, and mild-flavored aloe, which Williams-James uses in drinks. She teaches me about a plant called leaf of life, meant to help with respiratory ailments. She points out wild fennel sprigs as we walk past and talks about the Natal plums and Surinam cherries she turns into jellies.

Photo: Meredith Andrews

Palm trees at Spittal Pond.

She stoops down close to the ground and plucks furry light-green leaves off a shrub. “This is one of my favorite plants,” she says as she massages them in her palm, releasing a celery-meets-citrus fragrance. “Cuban thyme.” It’s invasive, she explains. If you plant it, it’ll take over, creeping like kudzu, swallowing anything in its path.

The Spanish explorers and British colonizers who staked their claims on Bermuda could have done the same thing, turning the island into an extension of their mainland identities. Instead of one culture dominating, all of the island’s inhabitants and influences come together in the crucible of time, creating something special. Many of the island’s signature things formed this way—stripping an idea down to its efficiencies, adding a little of this, a little of that, and a dash of resourcefulness. Everything from the Bermuda sloop to the rum swizzle stems from the same confluence and ingenuity. “Bermudian cuisine is defined by this sweet and salty pairing,” Weldon Wade, the diver, tells me one day as we stop into the little Mama Angie’s Coffee Shop for a sandwich of deep-fried silk snapper, lettuce, tomato, tartar sauce, sautéed Bermuda onions, cheese, hot sauce, and coleslaw piled on raisin bread. But perhaps an unexpected harmony extends to more than just the food here.

I take my sandwich to Southlands beach, to an isolated cove where I am the only visitor. I wash it down with a ginger beer. Southlands, a once-grand thirty-seven-acre estate, is now a national park. Banyan trees and Spanish bayonet plants with big bright white flowers cover the entrance and signal the beginning of something magnificent. Just steps away from the main road, the sound of traffic falls silent, these big old-growth trees serving as a sound barrier.

Ross MacDonald

No true wilderness remains in Bermuda, but there are places that have a certain wildness to them, and Southlands is like that—the forest is retaking what once belonged to it. Bermuda olivewood and palmetto trees fill in any available space, stretching to sunlight, their foliage covering everything in a sheen of bay-grape green. Moss makes its home between the sections of mortar holding the stones together. Ferns find a way to root into the eroding limestone, decorating walls with lush frills. Great kiskadees call from high up in the casuarina and cedar trees, reminding listeners how they got their name: Kiss-ka-dee! When they finally take flight, the birds burst in yellow streaks through the cloudless afternoon.

It will not take much longer for this verdant landscape, the closest I’ve been to something like a jungle, to feel like the ruins of a lost civilization. I allow myself to wander, photographing everything, chasing the footpaths wherever they lead, not worried about being late for the next excursion, or anxious about anything at all. For a little while I just follow my curiosity. It is a safe adventure. There are no venomous snakes on Bermuda, no scorpions. On an island that’s about twenty miles long and two miles wide, there is no true way to get lost. All paths lead to the sea.

Photo: Meredith Andrews

The shoreline at Daniel’s Head.

Sundays are sacred in Bermuda, just as they are in the South, and on my final day I make my way back to the water for one last sunrise. The sky is a dusky rose at first, and then rose gold. On this shore the sand is powdery and white. The kiskadees sing out again, perching in Brazilian pepper trees. The trilling of the short-billed dowitcher and calls of sandpipers and plovers create today’s harmony.

Out in the bay, I examine the reef: brain coral, fire coral, amber-colored sea rods—a veritable rainbow encased in cobalt below me. The islands of Bermuda sit on the lip of a long-extinct volcano. That is where these boiler reefs come from—the remnants of a once-powerful formation now silenced by the ocean. The reefs that caused so many problems for sailors, the markers in the sea I could spot from my plane, have become a sanctuary for me.

After almost a week here, my skin has taken on a honey-colored hue and I smile a bit easier, a smidge wider, a little longer. I thought I was coming to this island in the middle of the Atlantic to return to a state of wholeness. But I am not the same person I was before the hardships, before grief made its home in my rib cage, threatening to suffocate me. Still, I am also not the woman who arrived in Bermuda, washed up, worn out. The tension I carried is mostly gone. This place is what I know now, and what awaits me back home the question. I have not stopped looking for my grandmother everywhere. But now I think, maybe, she hears me.

I talk to the Atlantic as if it were a person, telling her all of this.

Photo: Meredith Andrews

Coral reefs on the way to Cooper’s Island.

I keep thinking about something Doreen Williams-James said about Mother Nature giving us what we need to survive, about destruction and hardscrabble beginnings becoming something beautiful. I think about Bermudiana blooming from the ashes. Maybe, even with the mended places and the rough edges, I could still be radiant. I still knew the stories of the stars and where to find them. My love for art endured, it just needed stirring. My passion for flowers too. Maybe remembering these things will allow me to bring a bit of Bermuda back to Appalachia with me.

I dip my feet into the blue one final time—my hands too, palms up, as if in prayer. I take in one last taste of the sea and breathe, deeply.

Thank you, I say out loud to the Atlantic, and then I leave the beach.

Latria Graham is a Garden & Gun contributing editor from Spartanburg, South Carolina, and writes the magazine’s This Land column, which documents aspects of the natural world in the South. An assistant professor of creative writing at Augusta University and an instructor for the University of Georgia's Narrative Nonfiction MFA program, Graham shares her adventures on Instagram (@mslatriagraham) and her work at LatriaGraham.com.