Arts & Culture

André Leon Talley’s Deep Southern Roots

The acclaimed fashion editor has served as confidant and adviser to Oscar de la Renta, dressed first ladies, and sat front row at every couture show that mattered. But his famous eye for style traces back to his grandmother’s house in Durham, North Carolina

Photo: Squire Fox

André Leon Talley, photographed at the Mint Museum in Charlotte in April.

On a clear and lovely Saturday evening last April in Charlotte, North Carolina, more than 450 guests gathered on the lawn of the city’s Mint Museum for its annual gala, a black-tie shindig called Coveted Couture, a reference

to the museum’s dazzling show The Glamour and Romance of Oscar de la Renta, which opened the next day. André Leon Talley, the towering (he is six foot six) former Vogue editor who was a close friend of the late designer’s and the curator of the exhibit, sat slightly apart from the crowd, bedecked in a stately Tom Ford cape made of black silk faille—“like those,” he informs me, “of the bishops and cardinals.” From his roost on a garden bench (where he was joined by Yvonne Cormier, a Houston anesthesiologist and philanthropist who has been one of Talley’s close friends since their days at Brown University), he chatted with the likes of actress January Jones and gallery owner Chandra Johnson (who is married to NASCAR mega-champ Jimmie Johnson) as a growing group of fans circled tentatively in hopes of an encounter with the great man, who graciously obliged: “And what is your name?…Of course, you can take a picture…So nice to meet you…love the dress.”

The event, a fund-raiser cochaired and envisioned by Laura Vinroot Poole, owner of the fashion-forward Charlotte boutique Capitol, also made the almost infinite list of what Talley is prone to call “moments,” intensified occasions invested with special excitement or emotion that could range from, say, the sight of me in the lettuce-green Scalamandré silk Carolina Herrera wedding dress he all but designed (“It was a moment, I tell you, a moment”) to the deep, deep pride he felt when he dressed and profiled Michelle Obama for Vogue (“I only wish my grandmother had been alive to see it”). This particular moment was especially significant because it marked a meeting of Talley’s two worlds: North Carolina, where he was raised by Bennie Frances Davis, the beloved grandmother he called Mama, during the dark days of the Jim Crow–era South, and what he refers to as the Chiffon Trenches, the rarefied world of high fashion where he has toiled for more than forty years as an editor, curator, commentator, and behind-the-scenes adviser and muse to countless designers, including de la Renta.

“To have the prodigal son come home after all his years in fashion and curate such a spectacular show in a changed South from the one he left felt important to me and, I think, to Charlotte,” Vinroot Poole told me. “We are so proud of all he’s accomplished, and I loved the opportunity to truly thank him for all that he has done.”

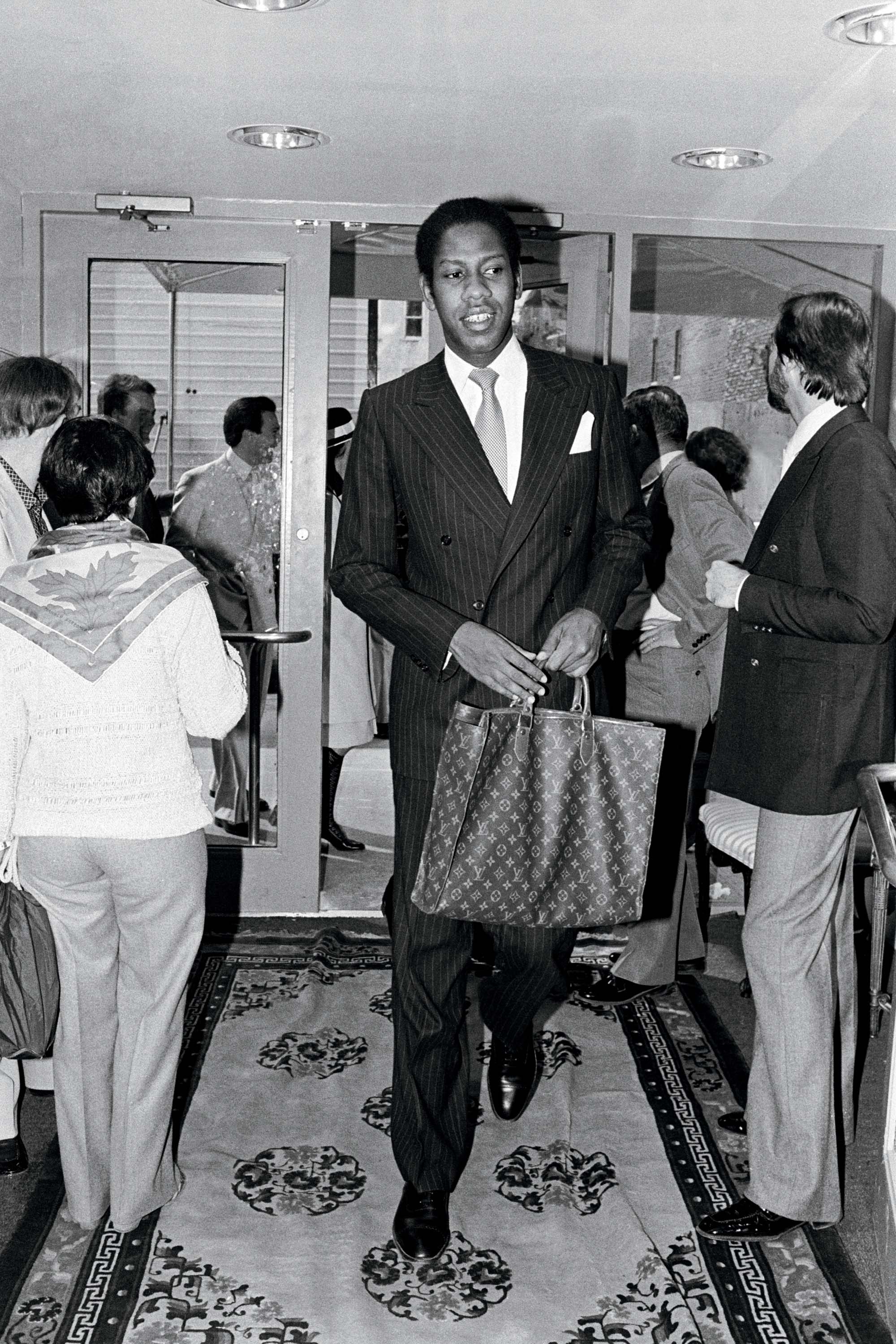

Photo: Dustin Pittman/Penske Media/REX/Shutterstock (6909156j)

Talley arriving at Christie’s East for a benefit in the late 1970s.

Talley, too, was proud—“I was proud to be in my state.” Though he grew up in Durham, just 142 miles away, he had never been to Charlotte until he spent weeks at work on the show, but he came away “impressed” with the city’s “beauty and Southern grace” as well as the “refined” gala with its “off the charts” Southern food and “extraordinary” flowers. “I was very, very happy,” he says. “I felt good about Charlotte and I felt good about the upcoming film.”

The film is The Gospel According to André, which had its Los Angeles opening just days after the gala and which has by now been shown in cities across America as well as in England, elsewhere in Europe, and Israel. An illuminating documentary by Kate Novack, it has precipitated an ongoing major (“major, maaa-jor”) moment and serves as what Talley calls the “gateway to the final chapter of my life”—one that is almost too big and too complex for a single film to capture (though Gospel tries mightily and is something of a mini-masterpiece). “It absolutely has shown the world who I am in a very emotionally honest way,” he says. “The love from the audiences has just been amazing.”

Of course, it could have gone the other way. “He’s courageous. He couldn’t know how the film would be received,” says his great friend Deeda Blair, the über-elegant fashion icon and medical philanthropist who has been at the forefront of cancer research for the past fifty years. “This film was a creative act. He’s an extraordinarily imaginative, creative person.”

That imagination and creativity were evident from his earliest days in Durham, where his grandmother worked five days a week as a maid cleaning the Duke University men’s dorm rooms. Like his affecting and beautifully written memoir, A.L.T., the film begins with his childhood. As he once told New Yorker writer Hilton Als: “You know what one fundamental difference between whites and blacks is? If there’s trouble at home for white people, they send the child to a psychiatrist. Black folks just send you to live with Grandma.”

Photo: Courtesy of André Leon Talley

Talley’s grandmother Bennie Frances Davis.

Thus it was that he arrived at Bennie Davis’s doorstep at Christmas in 1949, less than three months into his life.

It was in his grandmother’s pristine house—always cleaned and polished to the nth degree—that he learned the values he says have helped him navigate and survive the often “tortured” world of fashion, and though they were never forced on him, they were clear: “I learned how to live just by watching her work, pray, and go about the business of making a home for me.” It was also where he learned the true meaning of luxury—boiled, perfectly ironed sheets and starched white Sunday shirts; a well-tended rose garden and latticework piecrusts; “the beauty of ordinary tasks done well and in a good frame of mind.” They were lessons that never left him. “André has always understood that luxury provides distinction,” Blair says. “It’s all in the details. It’s not consumerism. He’s always talking about sheets.”

“My childhood, by anyone’s standards, was a rich one,” he says, adding that he took umbrage at a recent piece in the Guardian in which the writer referred to his “poor” upbringing. “Honey, we were not poor and I wanted her to know,” Talley says. “We were not on welfare, and we were not on food stamps. Wealth is based on values and traditions. I had food and unconditional love. I knew nothing about poverty.”

On Sunday mornings the tradition included a pan of his grandmother’s biscuits and the elaborate process of dressing for church. He remembers pulling on his starched and pressed boxer shorts, his grandmother’s handkerchiefs “folded as neat as a letter,” and, always, her hats. “Going to church, the way you dressed, you learned how to be,” he says. “In the black South, the church culture was almost like a finishing school.”

He excelled in actual school, but life was not without trauma. After church each week, he walked across town to Duke’s newsstand to buy the magazines that provided a window into a dramatically different world. On one such trek, a carload of students assaulted him with gravel. Then, as now, he remained undaunted. If the real world was cruel, fashion seemed kinder—or at any rate he could create his own fantasies. He installed a fake-fur bench in his bedroom; the pink walls were papered with the pages of Vogue, at the time edited by the brilliant Diana Vreeland, who would become the second most important woman in his life. At the public library he checked out Marylin Bender’s seminal The Beautiful People and The Fashionable Savages by John Fairchild, publisher and editor in chief of Women’s Wear Daily, where he would eventually work. During a visit home, his mother refused to walk through church with him wearing a navy maxicoat he’d procured from a flea market, but his grandmother never once wavered in her support.

He swears he became enamored with all things French by watching Julia Child on TV, and he couldn’t get enough of the subject in high school. At North Carolina Central University, he majored in French literature and spent summers in Washington, D.C., with his father, something of a “hepcat” who worked by day as a printing press operator and by night as a taxi driver. Talley himself earned spending money for the school year by serving as a park ranger at the Lincoln Memorial and splurged on fine gloves for his grandmother at the city’s haute department store Garfinckel’s. He made the local newspaper by winning a full scholarship to Brown, where he wrote his master’s thesis on Baudelaire and where he could finally spread his wings.

He and his friends from the nearby Rhode Island School of Design had extravagant dress-up parties. He wrote the social column in the RISD newspaper and bought a set of Louis Vuitton luggage with the money he made as a teaching assistant at Brown. Says his friend and former classmate Yvonne Cormier: “Even then, André just thought it was good manners to look wonderful.”

He left school for Manhattan after earning his master’s, sleeping on the floors of apartments belonging to some of his fancier school friends. When one of their fathers wrote a letter of recommendation to Vreeland, who had recently taken over the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, he won a slot as her volunteer assistant. They immediately became as thick as thieves—DV’s emphasis on the importance of maintenance and her habit of having the soles of her shoes polished with a rhinoceros horn were not so different from the polish that marked his grandmother’s house; Vreeland had an entire walk-in closet with floor-to-ceiling shelves of miraculous sheets.

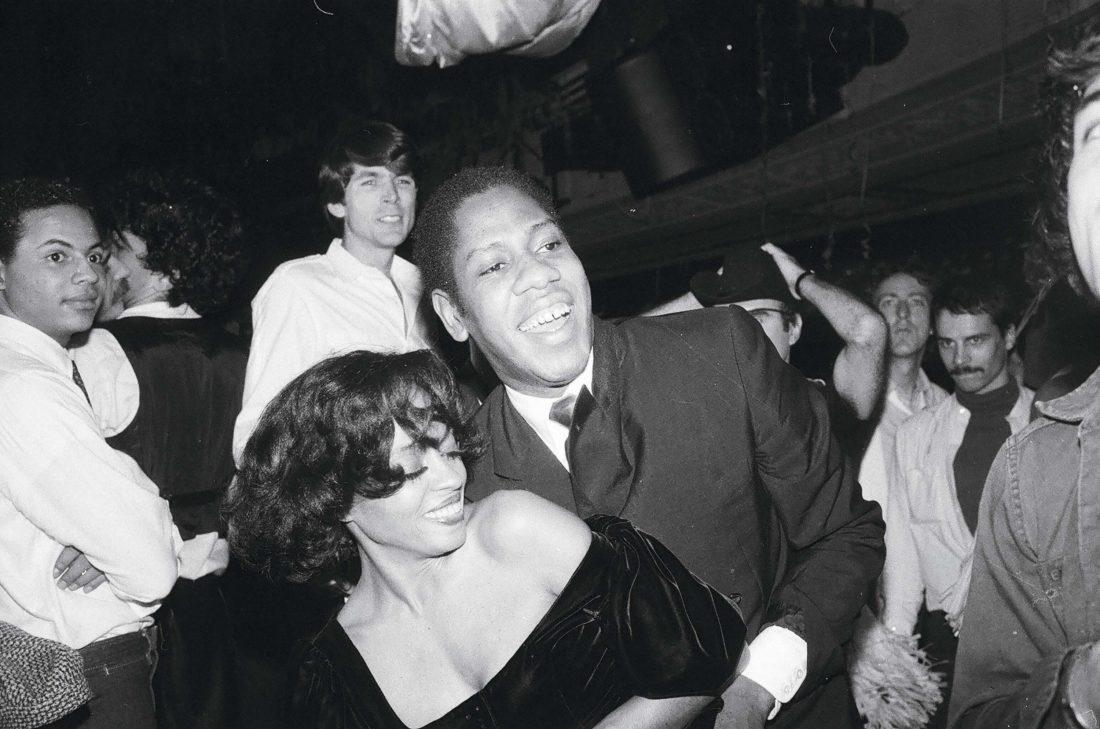

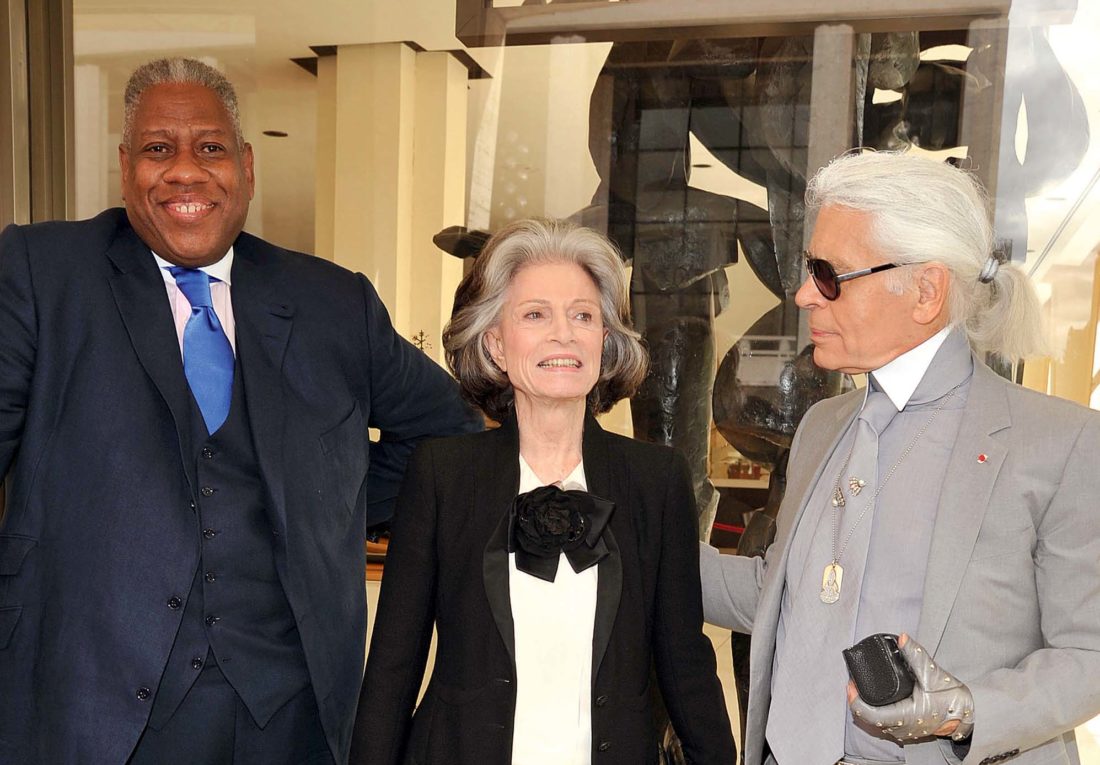

From the Met he got a paying job at Andy Warhol’s Interview, where he finally met the people he’d been reading about all his life. He danced every night at Studio 54 but never succumbed to the nightclub’s infamous sex-and-drugs scene (in the film, Fran Lebowitz describes him as “the nun” of the group). He interviewed Karl Lagerfeld, who became a lifelong friend, and hobnobbed with Naomi Sims and Pat Cleveland, the groundbreaking black models who had given him hope when he’d seen them on the pages of Vogue.

Photo: Sonia Moskowitz/Getty Images

Dancing with Diana Ross at Studio 54 in 1979.

During a long stint in Paris at WWD, the thin and beautiful young Talley cut a flamboyant swath at the fashion shows, but he also possessed a knowledge of fashion and its historic influences that was almost shocking in its depth and breadth. “André is one of the last of the great editors who knows what they are looking at, knows what they are seeing, knows where it came from,” declares the designer Tom Ford in the documentary. Or, in the words of Talley himself: “I got here because I had knowledge. As Judge Judy always says, they don’t keep me here for my looks. They keep me here for my power. Because knowledge is power.”

Upon his return to New York in the 1980s, he remained devoted to Vreeland, whose eyesight and health were failing and to whom he read almost every night. In 1988 he joined Anna Wintour when she replaced Grace Mirabella at Vogue, and in the following year both Vreeland and his grandmother died, only months apart. It was an enormous blow. He installed a granite obelisk carved to his exact height at his grandmother’s grave to signify his watching over her, and was the only non–family member at Vreeland’s funeral other than her two longtime nurses.

Though he is no longer on the Vogue masthead, he was inextricably linked to the magazine for almost thirty years, taking his seat alongside Wintour on the front row of every fashion show, escorting her to (and quietly dressing her for) almost every big-deal fashion event. The film, then, is the first thing in a long time that is his and his alone. “Finally,” he says, “it’s about me. It’s not about Vogue.”

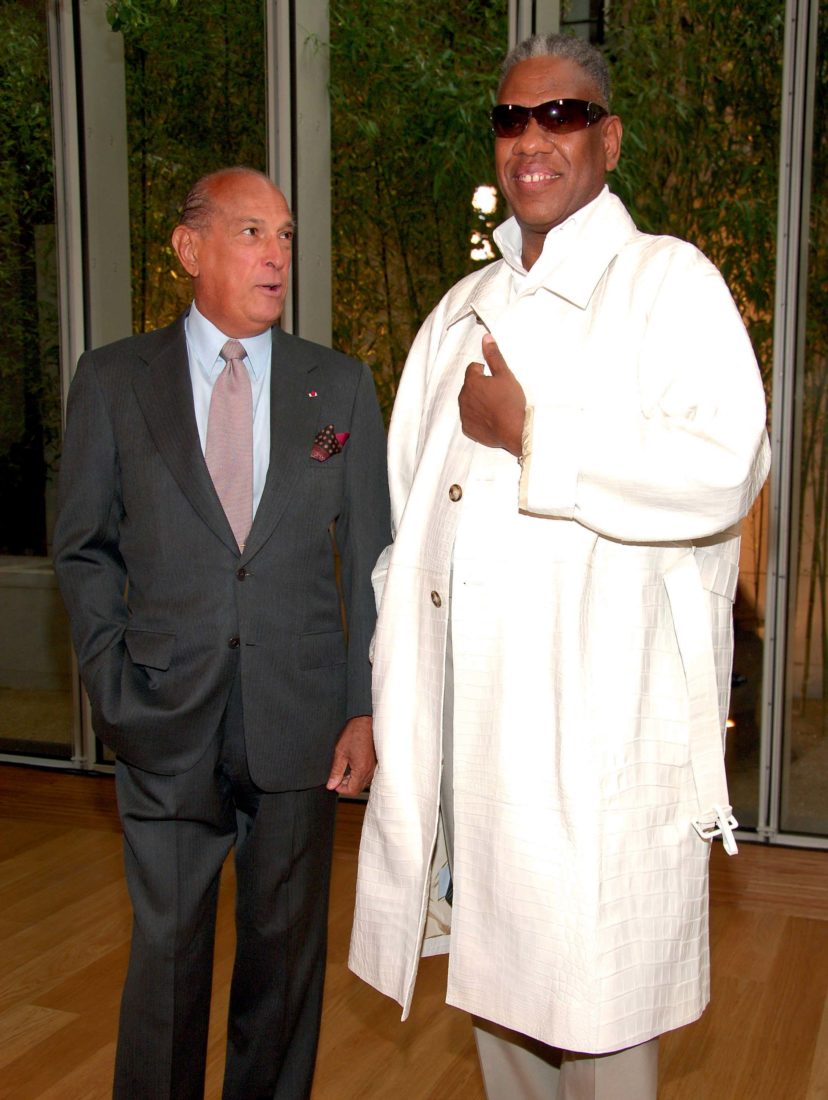

Photo: Jemal Countess/WireImage

In the front row with Anna Wintour at New York’s Fashion Week in 2007.

Still, it was in the hallways of the magazine that we first met and formed an instantaneous bond deriving from our mutual devotion to our innately elegant grandmothers, our memories of the food we so loved growing up, and our early obsession with the magazines that took us to the wider world. During projects together, he would jokingly refer to our employer as the Slave Ranch, and it is true that we worked extremely hard on stories ranging from the first-ever Vogue cover picturing a man—Cindy Crawford and her then-husband Richard Gere in Malibu—to a feature on John Galliano just after his first, earth-changing show. (We took the designer to lunch at Paris’s Caviar Kaspia, where Talley translated not just his often-slurred French but also the brilliant references that informed his clothes.)

We never failed to have a blast together, but it was on one of our trips that I also understood the racism and the slights that he had so long endured, despite his achievements and stature. We were tasked with producing a huge spread on Estée Lauder—she’d been furious about a piece called “The New Beauty Queens” in which her photo had been relegated to a page with her dead contemporaries Helena Rubinstein and Elizabeth Arden. When she threatened to pull her advertising from all of Condé Nast’s titles, including Vogue, we were dispatched to Palm Beach, but not before André hand carried some hastily whipped up couture gowns from Paris for the shoot. Since there was a direct American Airlines flight from Charles de Gaulle to Raleigh-Durham, he planned to spend the night with his grandmother, who was battling leukemia, before leaving the next morning for our assignment. Upon landing, he was taken aback by the appearance of two of Lauder’s armed security guards—she had no intention of allowing her clothes to stay in the house he’d bought for Bennie Davis for even a single night.

Photo: Squire Fox

Talley in the section of the exhibition devoted to the influence of Spain on Oscar de la Renta’s designs.

Ironically, it was in Paris that he endured the worst of it. A woman at Yves Saint Laurent dubbed him Queen Kong. One of his bosses at WWD told him his unparalleled access to designers must obviously have stemmed from the fact that he jumped in and out of all of their beds—which was patently untrue. “I was either a gay ape or a black buck servicing every designer in town,” he says. After the latter comment, Talley sought refuge in Le Madeleine—the same church, in a detail that only Talley would insert, where both Marlene Dietrich and Coco Chanel were eulogized—and thought for a long time before tendering his resignation. Even so, he says, “I bottled it up and internalized it. It hurt me very deeply.” But he was determined to make like his grandmother, to carry on doing the work with dignity rather than carry a placard: “I have fought quietly to impact the culture.” When in 2017 Edward Enninful became the first black man to lead British Vogue (or any mainstream fashion magazine, for that matter), Talley wrote him a note of congratulations. Enninful replied, “You paved the way,” a sentiment Talley described at the time as “the proudest moment” in his long career.

Photo: Michael Loccisano/Film Magic

Talley and Oscar de la Renta in New York City in 2006.

In the film and the many pieces that surrounded its release, he is more open than ever about the racism and loneliness he endured and the fragile friendships that exist in such a competitive, ephemeral world (Wintour is supportive sometimes, not so much at others, he says; Lagerfeld, for the moment, has gone dark). His friends applaud his bluntness. “I’m glad he’s doing that,” Deeda Blair says. “I don’t know why he hasn’t been more out there before now.”

What the film doesn’t always capture is Talley’s effervescent sense of humor and his boundless generosity and energy. There’s the obvious theatrical exuberance—and Lord knows he’s had to trot it out repeatedly over the years—but it’s infectious because there’s such a deep layer of genuine exuberance and delight underneath. After I gave him my grandfather’s silk top hat from Lock (who else on earth could I have given it to?), he faxed me an effusive note of thanks signed, in his large, loopy script, “Love, André, top hat on my head!” This was his period of nonstop faxes so brilliant in their almost stream-of-consciousness commentary that Wintour asked him to do a column based on them, and Vogue’s wildly popular StyleFax was born.

He is also a true-blue friend. When I aborted what would have been my first wedding and ill-advisedly went on the honeymoon anyway, Talley was there in Paris to hold my hand—and make a doomed trip entirely festive. The fun ceased as soon as the would-be groom and I arrived in Lyon, of course, but when I called Talley and told him I felt a bit like a piano wire was being stretched through my body, he didn’t miss a beat: “Get your lily-white ass on that fast train and meet me in the Ritz bar at 5:30.” I did and we settled in for more than six hours, during which I discovered the joys of a Pimm’s Royale, and a legion of Talley’s friends and admirers, ranging from the actress Arlene Dahl to two of Madonna’s bodyguards (she was giving a concert later in the week), joined us at our table.

When I finally did tie the knot in my hometown, he helped plan every inch of my wardrobe and descended into the Mississippi Delta for five days and nights. At one point during the festivities, the local bookstore hosted a party and a signing for the newly released A.L.T. that was so heavily attended by the locals that the mayor himself ended up directing traffic and Talley landed on the paper’s front page. Exhausted from the marathon, he fell asleep at the wheel on the way to catch his plane from Memphis and was discovered in the middle of a cotton field in his overturned rented Cadillac, still snoozing and suspended upside down by his seat belt, by a gobsmacked farmer. The nice man managed to get him on the plane to D.C., where Deeda Blair was hosting a book party in his honor, but most likely did not understand the supreme urgency of not keeping “Mrs. Blair” waiting.

As a thank-you for the party, he gave Blair a pair of Manolo Blahnik shoes, “black with gray and white embroidery,” she says. “André realized I needed them. I still have them. I’ll have them always.” In addition to such thoughtful gifts (when I got my first garden, he sent me two of his favorite brand of watering cans; when a dear friend wanted to see a Chanel show, he not only got the two of us some of the best seats in the house, but also plucked the hand-painted camellias right off the models’ lapels and pressed them into our hands), he is big on sharing his famous “moments” with those he loves—or indeed, creating them. Blair recalls a long lunch in Paris after which he took her to see Lagerfeld in his studio for a tour of the designer’s beautifully curated bookshop, which she hadn’t known was there. “We spent a magical afternoon with Karl,” she says. “I’d known Karl, of course, but it was sort of a heightened moment. And a heightened moment for André too—between two friends, a moment in time.”

Photo: Patrick McMullan

Talley with philanthropist and fashion icon Deeda Blair and designer Karl Lagerfeld in 2010.

Now, in his current moment, Talley says he hopes the film becomes “a good legacy piece for the ages…It can be shown in high schools, colleges, churches.” There is no question that his life and his accomplishments could provide inspiration to new generations, not least because he has always, always embodied the principles his grandmother instilled in him. His upbringing “was aristocratic in the highest sense of the word,” he declares on-screen. “You can be an aristocrat without being born into an aristocratic family.”

During much-needed downtime spent in his gracious white two-story house in White Plains, New York, he takes solace in that sentiment, in knowing exactly who he is and where he came from. He also revels in his garden full of boxwood and hydrangeas and dozens of enormous shady trees, in watching the birds and the resident rabbits from his front porch. As he wrote in A.L.T. fifteen years ago: “At the end of the rainbow that has led me to a successful career in the world of fashion…I find that the things that are most important to me are not the gossamer and gilt of the world I live in now, but my deep Southern roots…what matters is a sense of place, a sense of self.”