Home & Garden

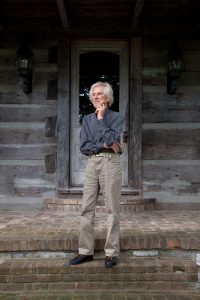

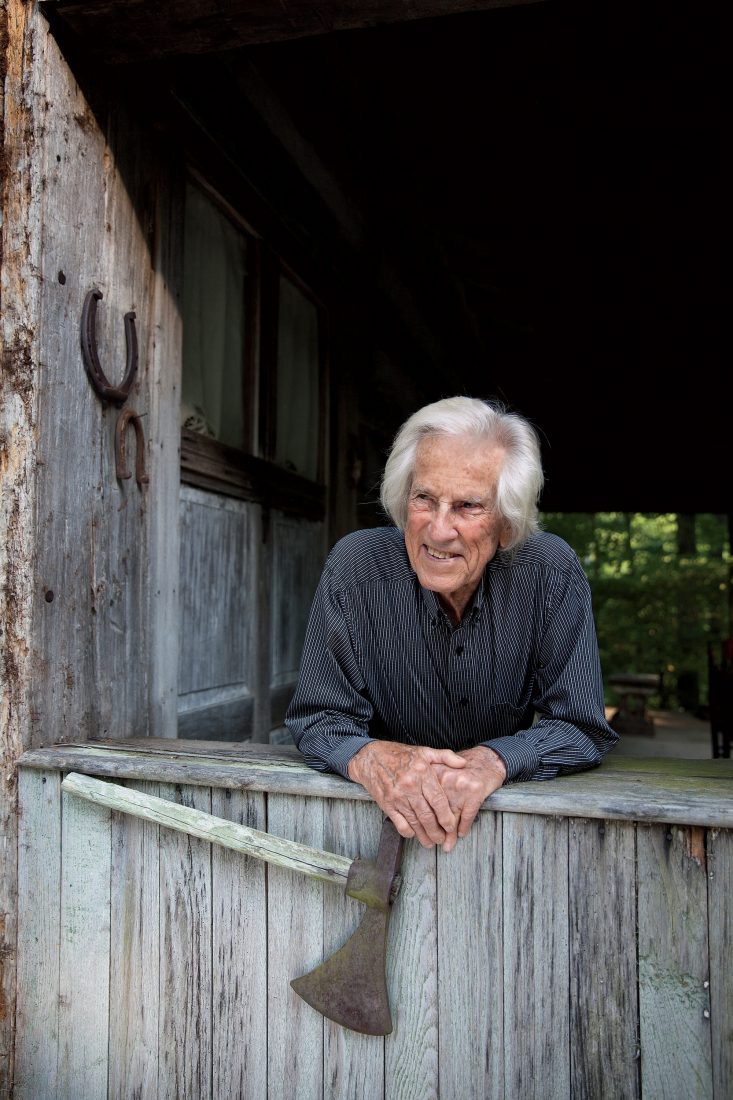

Built to Last: Braxton Dixon

Now in his nineties, the mastermind behind the homes of Johnny Cash and other country music greats is still building some of the world’s most unusual houses

Photo: Hollis Bennett

Two of the six houses on Dixon's hillside property.

As Braxton Dixon drives past an endless parade of cookie-cutter homes perched atop the Tennessee hills just northeast of Nashville, he looks out the window and considers whether he could ever build one. “Well, I just wouldn’t do it,” he finally says. “To me they’re ordinary, and there’s nothing wrong with that, but I love what I’m doing and I’m going to stay with it until I die.”

If there’s one thing in this world that isn’t ordinary, it’s Braxton Dixon. He has built the iconic homes of Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison, Marty Stuart, and Tammy Wynette, among many others, using centuries-old wood and one-of-a-kind architectural treasures sourced from run-down barns and other structures. Unlike the new construction buzzing past his window, Dixon’s houses are immaculately detailed works of art.

At ninety-two years old, Dixon is unbelievably youthful and undeniably cool. Like some sinewy Tennessee matador, he wears his pants high on his slender waist and bristles with a taut energy held, it seems, in endless reserve. His hair is long and full and swept back in a careless part over dark wraparound sunglasses, and his deep tan comes less from his Cherokee heritage than from the countless hours he spends in the sun, building. Still building. Always building.

Each detail in a Dixon house seems to have a story. These twenty-five-foot-long floor joists were taken out of a two-hundred-year-old tobacco barn. Those fifteen-foot-tall doors once hung in a steamboat captain’s house; this one in the home of Andrew Jackson’s law partner. That spiral staircase was once in a London train station; this brass sink in Nashville’s Lovelace Candy factory. And so on, the details of an architectural fantasy without end.

“It’s like living inside of a storybook,” says Christa Swartz, the resident of one tiny Dixon gem, a log cabin originally built in 1809 that Dixon rebuilt on his property in Hendersonville, Tennessee.

Dixon is not an architect; he is a master builder. It’s a distinction he’s keen to draw. There aren’t many left these days—builders capable of both designing and doing the hard labor. He works without plans, instead waking early and sketching out each day’s work on a scrap of paper that he then tacks up on-site, writing what materials will be needed along the bottom. Working hands-on with a small crew—usually no more than six people, and sometimes by himself—Dixon relies on building techniques that have stood the test of time. He eschews the three p’s—“plaster, plastic, and popguns” (aka nail guns)—still driving nails and setting huge stones by hand. He often moves the largest ones by simply rolling them over logs, the same technique ancient Egyptians used to place the stones of the great pyramids.

A salvaged bathtub––sent to Dixon by his World War II buddies in Italy––sits on cut Tennessee limestone.

A Dixon house can take three to seven years to complete, though he describes his process of taking down an old log building and reconstructing it elsewhere as “eight hours down; eight hours back up.” Most of the time is spent on Dixon’s legendary detail work, including his trademark habit of building distinctive architectural antiques into the very fabric of the house itself. Many of them are wild, such as a twenty-foot-long horse trough mounted above a mantel for use as a bookshelf. Others are miniature exercises in whimsy, like an antique brass wine spigot installed into a bathtub. At times, Dixon has been known to build an entire room around a single unique piece. But whether he’s crafting a kitchen table out of a loom or rebuilding a two-hundred-year-old horse barn with a spiral staircase and stained glass windows, it’s the quality of his craftsmanship that Dixon prides himself on the most.

“My father told me that every time you build a house, if the workmanship is the best, you’ll never be out of a job,” he says. “Well, I’ve never been out of a job in my whole life.”

Dixon’s wife, Maryanna, an elegant and accomplished cabaret singer, has been his inseparable partner for more than twenty years, though at times she still seems a touch astonished that her days are now spent dismantling old barns more often than performing onstage. “But what can I say?” she says. “He’s irresistible.”

Together, on land Roy Orbison once owned, the Dixons live in a log house Braxton originally built for Johnny Cash’s daughter Cindy and her then-husband, country music legend Marty Stuart. It’s one of six log buildings that Dixon has constructed around a central garden. Two are ongoing projects, one of which the Dixons plan to soon move into, making them the only couple I know of who have, with their own hands, built a new home so they can avoid going up and down the stairs in another.

Photo: Hollis Bennett

Wood Work

The kitchen of this Dixon house, in Tennessee, is covered in Portuguese cork.

The legend of Dixon’s entrance to this world is almost too perfect to believe. On a cold January night in 1921, his mother disembarked from a steamboat on the Cumberland River and gave birth to him inside of an abandoned log cabin. He stopped going to school after seventh grade to start working full-time with his father, a well-respected builder. By age fourteen, he had begun building his first house. It still stands in Hendersonville today.

While setting the stones in the chimney of that house, Dixon—who had been “out with the older boys” the night before and was moving rather slowly—was urged by his father to “put some heart into what you’re doing.” Dixon promptly carved a piece of limestone into a heart and set it near the chimney top. Every Dixon house since has featured a stone heart set high into its chimney.

“My father taught me everything I know,” Dixon says. But he’s carried more than just his father’s knowledge with him through the years. He still has his father’s toolbox and uses his grandfather’s handmade level on every job.

By the time Johnny Cash first approached Dixon about building a home, in 1967, Dixon had already been building his distinctive houses for thirty years. It was Cash, though, who introduced Dixon’s work to the world.

At the time, Dixon had a few plots outside of Nashville on Old Hickory Lake. He took Cash to see one. When they arrived, Cash saw an amazing sight: a huge structure built from reclaimed wood and stone, designed around two triangles meeting in its center and capped on each end with a glass-enclosed circle cantilevered out over the property. Cash jumped out of his Jeep and said, “That’s my house right there.”

What Cash didn’t know was the house he had just claimed was the one Dixon was building for himself.

Photo: Hollis Bennett

Dixon on the porch of an 1809 tollhouse, torn down and relocated to his property for use as a guest cabin.

“It’s not for sale,” Dixon said. But Cash wasn’t having it.

“You didn’t know it,” Cash said, “but you were building it for me all along.” He started making offers. As the bids increased in value, Dixon kept turning them down. Finally, he relented when Cash reached a number too high to pass up ($150,000!). “Mr. Cash,” he said, “you just bought yourself a new house.”

The doors to the home were six inches thick, made from wood pulled out of an old wharf in Charleston, South Carolina. They came with two keys, each almost a foot long. When Dixon handed them to Cash, Cash gave one back. “This is your house as long as it’s my house,” he said. That marked the beginning of almost four decades of the closest possible friendship.

“They were blood brothers,” says Marty Stuart, who later became a Cash band member (as well as his son-in-law, for a time) and frequently spent time with Dixon and Cash together. Perhaps it was a similar background, or a shared ambition. Maybe it was the sparks sent off from two artists in the same space. Whatever it was, Dixon and Cash had a lifelong connection and together made quite an impression. “They were just country boys—but elegant, worldly country boys,” Stuart says, his voice still tinged with awe.

Now a close friend of Dixon’s himself and the owner of one of his finest houses, Stuart remembers first wondering about Dixon when, as a young fan of Cash’s, he would read articles about the singer and see Dixon’s name. It piqued an interest that only increased with time. “It was always a dream of mine to live in one of Braxton’s creations.”

Hollis Bennett

The eclectic, catty-corner entrance to Dixon’s home, draped with Boston ivy.

Another admirer, Barry Gibb of the Bee Gees, bought Cash’s house two years after the legend’s death and began a total restoration of the home. Just over a year later, while a crew was working on-site, the house went up in flames.

“I just kept saying, ‘I can’t believe it,’” Dixon says, pausing, as if still coming to terms with the loss. “It’s not just seven years of building it—it’s all the years of beauty spent inside of it.”

Of the fifty-one houses Dixon has built, only one is open to the public: the Thistletop Inn, an intimate and immaculate bed-and- breakfast on a shaded hillside in Goodlettsville, Tennessee. Named after the floor-to-ceiling window in its master bedroom—a 150-year-old piece of etched glass featuring the pattern of a thistle and a rose that Dixon found in a convent in Kentucky—the inn is constructed out of huge exposed beams, some fifty-two feet long, relocated from another Charleston wharf, a Nashville candy factory, an Indiana train station, and a North Carolina tobacco warehouse.

“Braxton holds dear the things that are the best about American craftsmanship: a reverence for tools and material,” says Fred Peace, who, with his wife, Mary Jane, runs the inn. “That kind of focus is few and far between.”

In addition to his craft, Dixon has made an art of scouting the structures from which he draws much of his material. He has offered rewards to rural mail carriers for finding abandoned buildings. He has flashed a $100 bill to a group of boys playing in a country field, promising it to anyone who found him an old house. He says he’s taken down more than twenty train stations. “And I’m still out there on the prowl,” he says, only three days before driving to Topeka, Kansas, to scout yet another aging barn.

It was Dixon’s father who first started his love affair with vintage lumber. He cut loose a bundle of fresh wood so that Dixon, then a boy, could see how each piece, newly warped, would spring away in a different direction. “Son,” he said, “I will not build a house out of that.” It’s a lesson Dixon learned well. He says he hasn’t used a piece of new wood in seventy- five years. “Brack Dixon has been doing green since before they knew what green was,” Maryanna says.

Although his materials are centuries old, many of Dixon’s houses are extremely modern. One was based on the design of a Moroccan camel saddle, another on the shape of Sally Field’s head wear in The Flying Nun. The “House of Doors” was built completely—from the siding to the flooring—out of, you guessed it, doors. Dixon recalls with relish the story of the BBC reporter who once, when visiting Cash’s house, told his listeners that he was in “the most unusual home in the world.”

Photo: Hollis Bennett

A self-supporting staircase includes a brass casket handle for a railing.

There is little chance the world will ever see another builder quite like Dixon. “If there is one,” he says, “I don’t know him.” But while time spent in a Dixon house is unlike almost anything else—comfortable and graceful and removed from the rush of the modern world—Dixon’s singular aesthetic eye affects more than just the feeling you get when you step inside one of his homes.

“What Braxton has taught me about life,” says Marty Stuart, “is that there is beauty in almost everything.” If only every house could work that potent magic.

Photo: Hollis Bennett

A staircase in the main house, made of antebellum poplar.