Gardens

Charles Stick: The Path Less Taken

For the renowned Virginia designer Charles Stick, landscape architecture is much more than a profession. It’s a never-ending quest for beauty

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

Six autumns ago, the Virginia-based landscape architect Charles Stick was designing a courtyard garden for a client in Houston. In the middle of the job, Stick traveled to Kyoto, Japan, for twelve days. “There I was, walking through one of the great imperial gardens, and there are men up on ladders,” he says, in a slow, honeyed baritone. “They have these white gloves on, and they’re pruning the needles out of the pine trees with their fingers.” Another day, outside a shop front, he noticed a wooden tub containing a small Japanese maple, its leaves aflame in red. A woman stepped out of the shop, whisked up the few leaves that had fallen to the sidewalk with a rush broom, and carried them inside. Then she returned, grasped the tree’s stem, and gently shook. When more leaves fell, she swept those up and slipped back into the shop.

“That trip was one of the most shattering experiences for me,” Stick remembers. “This is a culture that has taken the craft of gardening and refined it to such a high level that from a Western perspective, it’s almost unfathomable. That, to my mind, is an appreciation of beauty that is to be admired and even longed for.”

When the designer returned to Texas, his client asked about his trip. “I said, ‘You know, I’ve never been so influenced by what I saw in my life.’ And she says to me, ‘Well, Charles, I sure hope that you finish my little garden before you become too influenced!’”

Like most people who hire Charles J. Stick, she had done so because of his reputation as one of the country’s leading classicists, a man trained at the University of Virginia during the 1980s, back when, according to Stick, “you hired a UVA grad because you knew what you were going to get.” But beauty, not orthodoxy, is Stick’s true master, and these days, as he approaches the age of fifty, something akin to a midlife crisis is pushing him deeper into his art.

“Charles is a devotee of beauty,” says Charlottesville architect Russell Skinner, who has worked with Stick off and on for two decades. “He has committed his life to the pursuit of making beautiful things. He is uncompromising. I’m constantly giving ground to clients and contractors. Charles, on the other hand, is insistent, and he has a wonderful ability to bring his clients along on the adventure.”

Over the years, Stick could easily have followed the path of other popular landscape architects by hiring a raft of newly minted designers and draftsmen and growing his firm to meet demand. But his ambitions are more elusive and personal. He has no cable television show, blog, or Twitter account. He does not employ a PR agency to market his “brand.” His firm doesn’t even have a website. Instead, he finds clients serendipitously, more and more often turning down those who don’t share his seriousness of purpose, while cherishing his relationship with a few kindred spirits who accompany him on pilgrimages to study the great gardens of Europe—Villa Cetinale near Siena, Sissinghurst in Kent, André Le Nôtre’s Vaux-le-Vicomte—in search of ways humans have imposed order on nature.

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

An elegant tableau of Stick's labor of love, Waverley Farm.

“In my mind, beauty has very little to do with fashion,” Stick says. “Fashion is transient. Beauty has more to do with an understanding of history. I had a professor at UVA named Harry Porter. Harry would go out to lunch and have a few pops and come back and do our design critiques. One day, he got sort of belligerent. We all had our drawings on the wall. He said, ‘Listen. You people need to know something. Everything that’s beautiful has been done before, and if you keep doing work like this, you’re going to end up drawing other people’s ideas for the rest of your lives.’ Then he stormed out. I subscribe to that notion.”

And where does that leave Stick?

“That leaves me devoted to understanding what’s been done before. If you have an understanding of historic precedence, you can be facile. If you don’t, you’re dead in the water.”

In recent years, Stick has deepened his well of knowledge by visiting Islamic gardens—places of rest and reflection meant to symbolize paradise—in places like Morocco and Turkey. A stroll through the charbagh at the Taj Majal left him speechless. He speaks of walking across India, of shedding his material possessions for more spiritual pursuits. “I’m searching for a way of expanding my consciousness somehow to be able to get beneath the skin of beauty, which has been so important to me. I need to sharpen my powers of awareness.”

Before he was old enough to mow the family lawn, Charles Stick’s passion was hockey, a sport known less for beauty than for brutality. One of three children of a sporting-goods sales rep and his wife, who lived on an elm-lined street two blocks from the busy Burlington Northern rail line in Western Springs, Illinois, a working-class suburb of Chicago, Charles first laced up his skates when he was eight. His parents were practical but supportive, he says, pushing him toward a college hockey scholarship and perhaps even a shot at the pros. Although he had no exposure to landscape design as a child, he learned to love gardening from his mother’s stepmother in Michigan. “I can still picture these wonderful seed packages, with abstract paintings of vegetables and black writing at the top,” he says. “There was always that sense of potential wrapped up in the garden. That damn seed could turn into one of those big watermelons with the bright colors.” During summers, he raised squash, cucumbers, and flowers behind his family’s stucco Foursquare, staking his tomatoes with broken hockey sticks.

Throughout his youth, Stick seemed destined to escape his circumscribed life. He chose Middlebury College in Vermont, a private school that, to his parents’ chagrin, offered no free rides for hockey players. Stick helped pay the exorbitant tuition with money he earned as a golf course greenskeeper. During his second year, he quit hockey and threw his passion into geology, specifically morphology, the study of landforms and the effects of forces such as glaciers and plate tectonics on the earth’s crust. After nearly disowning him for quitting a sport they had sacrificed so much to support, Stick says, his parents regained their faith, confident their son would succeed as a petroleum geologist. Then Stick met Dan Kiley.

Smitten by a “string bean of a girl from Montana,” Stick followed her to a dining-hall lecture given by Kiley, a landscape architect commissioned by Middlebury to redesign its campus. A towering twentieth-century figure who designed landscapes for Lincoln Center in New York, Eero Saarinen’s Gateway Arch in St. Louis, and I. M. Pei’s East Building for the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., Kiley was his own force of nature, imposing a human order on the landscape using the classical tenets of sacred geometry and the Fibonacci numbers. “That’s when it gelled for me,” Stick says.

He had returned to Western Springs when he told his parents he wanted to go to graduate school to study landscape architecture. This was a town where people rarely hired lawn services, much less architects for their yards. Though humans have been altering the landscape since time immemorial, not until 1863 did Frederick Law Olmsted first use “landscape architect” as a professional title. Even in the early 1980s the profession was still relatively young. Stick’s mother could not hide her disdain. “She looked at me,” the designer remembers, “and said, ‘That’s a waste of a good education.’”

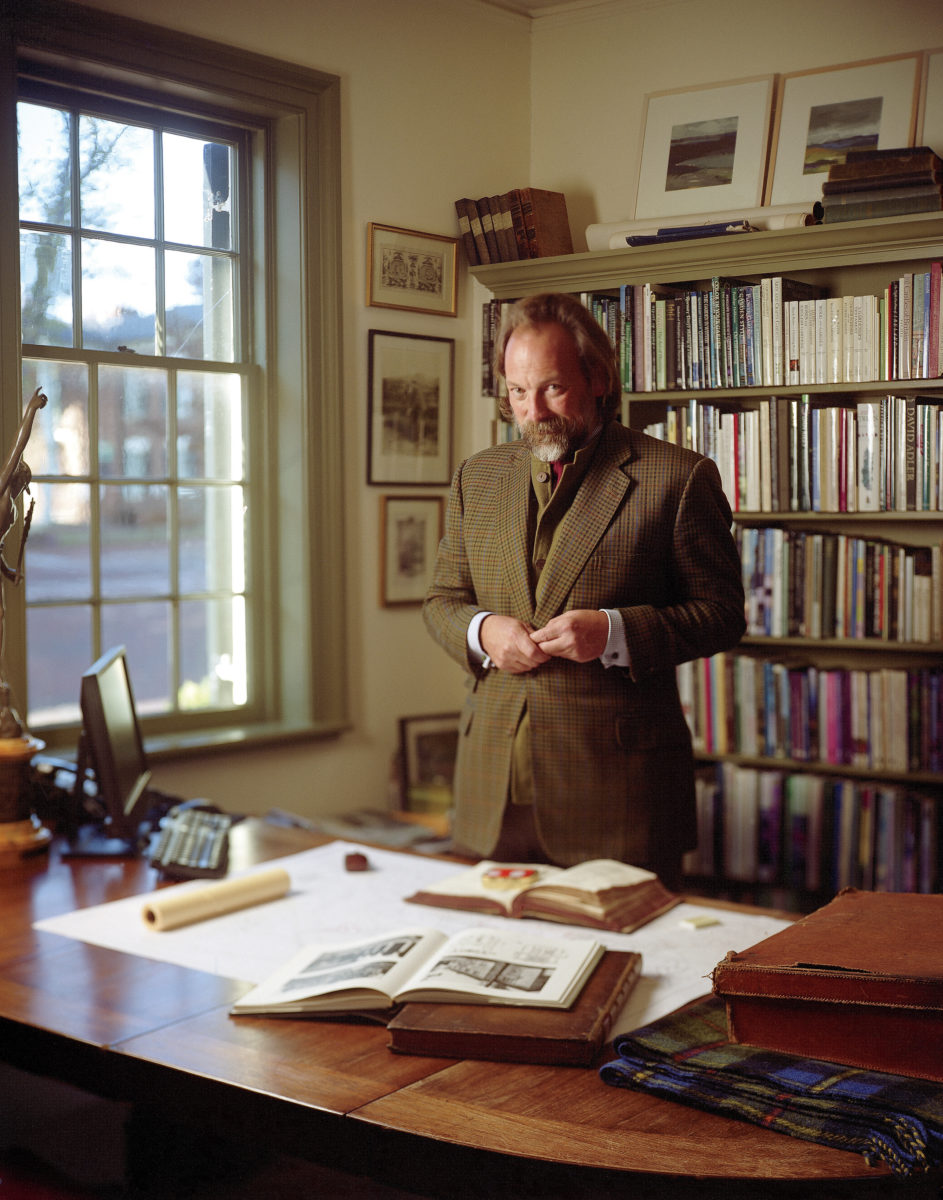

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

Stick in his two-hundred-year-old headquarters in Charlottesville, near his beloved UVA campus and Thomas Jefferson's Monticello.

Stick plowed ahead anyway, and during a springtime visit to the University of Virginia, beguiled by his first whiff of English boxwood, he discovered neoclassicism, specifically the architecture of the ancient Greeks and Romans as interpreted by Thomas Jefferson via the sixteenth-century Venetian architect Andrea Palladio. The focus on simplicity and order resonated with him. “I remember walking on the Lawn for the first time. I passed the Rotunda and looked up at the entablatures and cornices around the pavilion, at the richness of the shadows against the white woodwork, and I thought, This is a deep, deep reservoir. I can be happy here for three years learning this vocabulary.”

“Charles was an outstanding student of history and loved the Italian Renaissance,” recalls UVA landscape architecture professor emeritus Reuben Rainey. A quarter century later, Stick is still in Charlottesville. After spending six years working for an aristocratic Belgian named François Goffinet, a man with international connections but little formal training, Stick opened his own small firm, employing a pair of landscape architects. He hung his shingle (literally) on the wall of a cramped but charming book-filled two-hundred-year-old brick cottage a mere three miles from Jefferson’s Monticello. Virginia, with its agrarian roots, genteel pace, and reverence for Palladian architecture, suits him just fine. “What seems harmonious to me in terms of my life is right here,” he says. “To this day, when I walk into the Lawn, I find it has an almost sacred quality.”

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

Boxwoods frame the vegetable garden at Stick's Waverley Farm.

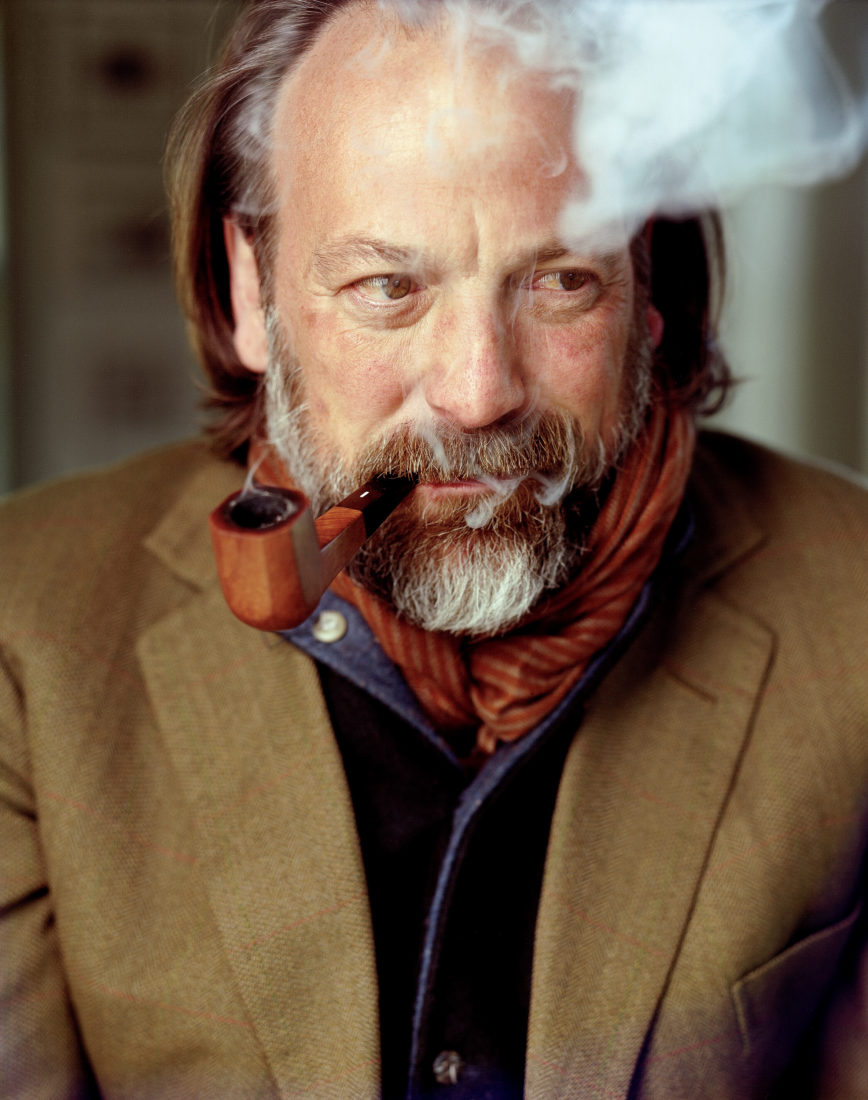

Pausing beside his black 1997 Audi station wagon on a circular auto court he designed, Stick removes tobacco from a tin and carefully tamps the earthy clump into the bowl of a wooden pipe. Puffing away, nattily dressed in a tan blazer, a bow tie, and dark gabardine pants, he cuts a striking figure. With wavy hair swept back and cut Dutch Boy square above the shoulders and a thick but impeccably trimmed beard, he looks equal parts literature professor, English aristocrat, and Wild West gambler. Behind him looms an early nineteenth-century brick farmhouse. Pea gravel crunches underfoot as we stroll to the top of a stone staircase and peer out over a vast maze of ten-foot-tall boxwoods, grown from sprigs plucked nearly a century ago from a neighboring home, James Madison’s Montpelier.

We’ve come to Waverley Farm, nestled in the Blue Ridge foothills north of Charlottesville, to see Stick’s decade-long labor of love. Here he has put into place his core aesthetic principles, the most important being what the nineteenth-century landscape designer and artist Charles Platt, a major influence on Stick, called the “comprehensive whole”—a unity between house and garden. Before Stick got his hands on it, the garden was adrift, separated from the house by a slope and a gulf of fescue. Installing a stone patio and steps, he linked the boxwood maze to the house with a path lined by newly planted boxwoods, evenly spaced to create a cadence that beckons a visitor to enter.

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

The Basin Garden, one of many hidden surprises at Waverley Farm.

Crossing the leafy threshold, we encounter a series of outdoor rooms, each with a surprise: a burbling fountain flanked by a row of Elizabethan-style hand-carved and gilded “beasties” on poles; a bronze statue of Mercury, anchored to the earth but reaching to the heavens; a single Yoshino cherry tree, whose pink blossoms fade to white each spring. “The idea was to give someone moving through the landscape a sense of discovery,” Stick explains, “to create layers of unfolding experience.”

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

A statue of Narcissus over the farm’s reflecting pool.

Nowhere is that concept of movement and discovery more fully realized than in the extraordinary garden Stick has designed over the past fifteen years for Fred Landman, of Greenwich, Connecticut. Beyond the formal fringe of Landman’s 1930s Georgian Revival house, with its boxwood parterre shaped in an impossibly intricate paisley pattern, Stick introduced a “golden path” (named for a similar feature created by the landscape architect Russell Page for the PepsiCo Sculpture Gardens in Purchase, New York), which meanders through nine acres of garden vignettes, including a hidden petanque court and a Chinese pavilion on a floating island. Along the path, two horizontal dogwood trees frame a hidden grotto built into a cliff, where azaleas, sweet woodruff, toad lilies, silver bells, witch hazel, and narcissus spring from the loamy woodland. Farther on, a Spanish cedar walkway spans a small wetland planted with 15,000 irises. For two weeks each spring, the meadow blooms in shades of blue, with a thin line of white flowers and a smattering of red. Landman calls it painting with flowers. In all, he and Stick have planted more than 400,000 bulbs. “I’ve had people get lost here and come back with their jaw hanging down,” Landman tells me. “Not physically lost but emotionally lost. Step around every corner, and you’re in this whole other world. It’s magical.”

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

Stick strikes a pose under Waverley's hornbeam arbor, on a bench from Orsan Gardens, near Paris.

Back at Waverley Farm, Stick and I continue our ramble, past rose arbors and beneath hornbeam arches, eventually entering a vast kitchen garden. Except for a few rows of greens, it lies dormant until the next growing season. Even this, the most practical section of Stick’s garden, is laid out with meticulous precision. Neatly trimmed boxwood parterres studded with topiary works in progress—Stick’s own experimentation—frame the vegetable beds. “Can you have a practical garden for sustenance and make it beautiful?” Stick muses. “Jefferson said yes.”

The gesture traces back to Stick’s tomato vines and hockey sticks, his need to order the landscape. Who knows where that urge will take him next?

“I actually think we’re all divine beings,” he says. “I’m not well versed enough to know what that means in terms of a Judeo-Christian concept, but I know in my own soul my life is very, very special. That is part of why I feel obligated to make something more beautiful.”